Maloney can stake claim to greatest Reds’ pitcher

Published 1:29 am Saturday, April 4, 2020

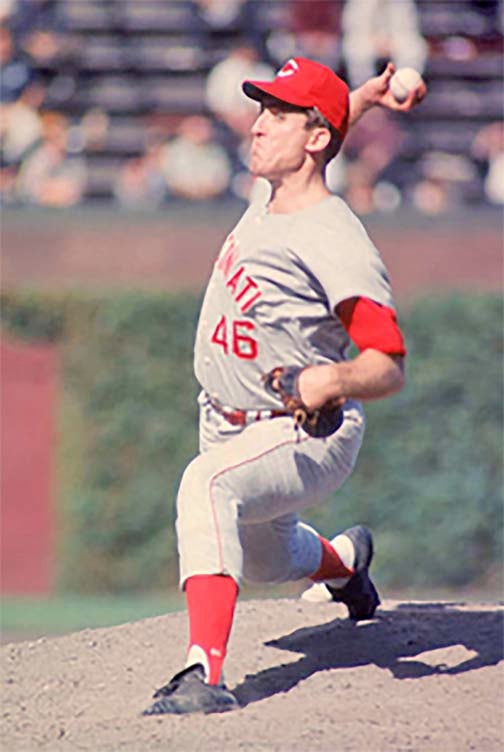

Former Cincinnati Reds’ pitcher Jim Maloney delivers a pitch during his 10-inning no-hitter as he beat the Cubs 1-0 in Chicago August 19, 1965. (Associated Press)

Jim Walker

jim.walker@irontontribune.com

FRESNO, CA — Jim Maloney strove for perfection. He settled for greatness.

The pitcher with a .44 magnum for a right arm was on a path to become a member of Major League Baseball’s Hall of Fame only to be derailed by injury.

But before a ruptured Achilles tendon halted his career after 10 full seasons, Maloney put up numbers so impressive that he is considered the greatest pitcher in Cincinnati Reds history.

Maloney had two no-hitters and a rule change in 1971 by Major League Baseball erased a 10-inning no-hitter that ended up a 2-0 loss in 11 innings. He also had five one-hitters.

“I felt that way,” Maloney said in reference to being a threat to throw a no-hitter each time he took the mound.

“That’s how I stayed in the game. I always said I was going to pitch a perfect game. So, I’d start and get the first guy out and I’d say I’ve got 26 more. I’d get the next guy and say I have 25 more. If a guy got a hit off me, I’d say I’m going to throw a one-hit shutout. I felt that I had a chance to pitch a no-hitter every time I went out there or a perfect game.”

Obviously, Maloney didn’t throw a no-hitter each time he pitched but he was a threat and he did accomplish the feat twice.

Ironically, his best no-hit performance was his first no-hitter when he pitched 10 hitless innings in a home game against the New York Mets on June 15, 1965. But while Maloney was shutting down the Mets, the Reds failed to dent the plate and Maloney lost the game 2-0 in 11 innings as he gave up two hits in the inning including a home run by Johnny Lewis.

Maloney struck out 18 batters to set a record for most strikeouts in an extra inning game.

“That night was probably as good of stuff as I ever had. Billy Cowan was the leadoff hitter for the Mets and later on we were teammates with the (California) when I got traded to the Angels and Cowan was already there,” said Maloney.

“(Cowan) told me when he faced me that night that I threw him two fastballs and a curve and ‘I never got the bat off my shoulder and went back to the dugout and I told my teammates you can forget it tonight boys.’ That’s what he told me.”

Two months later on August 19, Maloney must have had a feeling of Déjà vu.

Although his control was eratic, Maloney was still throwing hard. He struck out 12 but walked 10 as he threw 187 pitches.

“They had no pitch counts. If you were throwing the ball good and getting guys out, the way the manager could tell and the way you could tell was they started getting good swings on me and started getting better contact on the ball and I wasn’t fooling anybody or I couldn’t get the ball by somebody. The hitters would let the manager know (the pitcher) was losing a little bit of his stuff,” said Maloney.

“When I got to the ninth inning I was sitting on the bench and I looked at the scoreboard and I’m thinking to myself two months have gone by and I’m in the same position. It’s hard to stay positive. I’ve got to go out there and not give up a run or I get beat because we’re playing in Chicago and we have no chance to come back. I was on deck and (shortstop) Leo (Cardenas) hit a ball that I could see was curving. He had enough to get it out I thought. He hooked it and it hit the flag pole maybe 10 feet above the wall for a home run. I went back out the next inning and I walked the first guy and the second guy got out and then I got Ernie Banks to hit into a double play. In two months time, I won a 10-inning no-hitter and I lost a 10-inning no-hitter.

“I was in trouble in every inning basically. I walked a lot of guys, I was 3-2 on guys. It was a really sloppy game. I just made the right pitch at the right time. I was throwing the ball good. I was throwing the ball great as far as that goes. But, I wasn’t on like I was with the Mets. I had a bunch of strikeouts against the Mets.”

The second or third no-hitter depending on who is keeping score came on April 30, 1969 when Maloney beat the Houston Astros 10-0.

“That game was nothing like the other games. I knew I had a no-hitter the whole way, but any time a team gets you a bunch of runs like that it’s much easier to go,” said Maloney.

“But you have to keep in the frame of mind that it’s like a zero-zero game and just go through the motions like this is going to happen. You can get yourself in trouble. You have to stay in the game mentally and each hitter say, ‘this is it.’”

In that no-hitter, Maloney struck out 13 and walked five. In a rare occurrence, the Astros’ Don Wilson pitched a no-hitter the next night to beat the Reds 4-0.

Catching the no-hitter against the Astros was 20-year-old Johnny Bench who was the NL Rookie of the Year in 1968 and won the first of two MVP awards in 1970. Bench went on to be elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame.

Maloney said everyone knew Bench was a future Hall of Fame player from the onset, but the two also share an interesting story from the ’68 season.

“(Bench) came up about ’67 or ’68 and I was losing a little bit off my fastball and I needed another pitch that I could use to get batters out. I was at home and talking to this guy and he started talking about (New York Yankees pitcher) Whitey Ford who was throwing a spitter. This guy was a Yankees fan and he was my wife’s OBGYN. He lived in Fresno and we became friends. He said, ‘You know, that might be a good pitch for you.’ I said I’d never tried throwing a spitter,” said Maloney.

“In those days, guys were throwing a spitter and they didn’t do much about it. He gave me a couple of tubes of K-Y jelly and I took it to spring training and started fooling around with it. I came up with a terrific pitch and you couldn’t hit it. A catcher would need a sign or he wasn’t going to catch it.

“So, when Bench came up I told him I had this pitch and you’ll need a sign for it because I never know which way it’s going to go. It comes in there like a fastball in the high 90s and then just explodes. It goes down or down and away or straight down. There’s no way of tracking it the same, you just have to be ready. He told me, ‘You throw it and I’ll catch it.’ He was pretty cocky in those days. He knew he was a Hall of Famer and everybody knew that with the talent he had at 19, 20 years old.

“I started a game in Cincinnati at Crosley Field and got a couple of outs in the first inning and he calls for a fastball and I loaded it up. I had it on the back of my neck. I put a little dab on my fingers and put it on the smooth part of the ball and wound up and threw it and he never got a glove on it and it hit him on the toe. I got the guy out and went back to the bench in the dugout and I figured he was going to say something but he didn’t say anything.

“I did the same thing in the next inning. I got two outs and I wasn’t going to try it with anybody on base because he wasn’t going to catch it. I threw it and it went up high and he jumped up a little bit and it came down and hit him in the cup and broke his cup. He went down on all fours at home plate and he was moaning and yelling. They finally revived him a little bit and I got a new ball and was walking back up on the mound and I turned around and he was right behind me. He had his mask up on his head and he said, ‘I think I need a sign for that pitch.’ He tells that story a lot.”

Bench not only caught Maloney, but in All-Star Games he caught other great fastball pitchers such as Don Drysdale, Bob Gibson, Steve Carlton, Mario Soto and Tom Seaver. Bench said Maloney threw harder than anyone he ever caught.

“He wore me out,” said Bench.

Despite his misfortune with the Achilles tendon injury plus arm trouble that forced him to take cortisone injections in order to pitch, Maloney has no regrets.

“To be honest, I’m grateful of the time I got. I got to pitch against some Hall of Fame players — Willie Mays, Willie McCovey, Hank Aaron, Roberto Clemente — I got to play at Crosley Field and that was my time,” said Maloney.

“We had a chance to win in ’64, we won (the pennant) in ’61 and I was part of that. In ’70 I was on the disabled list the whole time and that was another time we won (the pennant). The Big Red Machine was a great group of guys and I knew most of them. They had good pitching and hitting and you take Bench, Rose, Morgan and Perez and those guys were good. Sparky (Anderson) didn’t have to manage. He just had to let them play.”

The injury came early in the 1970 season just as the Big Red Machine era was revving up its engine. The man who could have been the face of a good Reds’ pitching staff during the 1970s had to settle for a spectator’s role.

“I don’t dwell on it. I did have a rough time when I had to get out of baseball. It came within a year and a half and I was out of baseball,” said Maloney. “I had a tough time sliding back into the real world.

The Reds went on to win four National League pennants and win back-to-back World Championships in 1975-76 that established Cincinnati as one of the greatest teams in baseball history.

No one could blame Maloney if he felt cheated. The numbers he put up during his career with the Reds were more than impressive. In fact, it was the Reds and their fans who were cheated.

The 6-foot-2, 190-pound right-hander broke in with the Reds in 1960 and had an inauspicious start as he went 2-6 with a 4.66 earned run average in just 11 games. However, he struck out 48 in 63.2 innings.

He became a full-time starter in 1961 and went 6-7 with a 4.37 ERA and 57 strikeouts and 59 walks in 94.2 innings as the Reds won the NL pennant but lost the World Series in five games to the New York Yankees.

Maloney’s fortunes began to turn the next season as he went 9-7 with a 3.51 ERA and whiffed 105 batters in 115.1 innings.

His breakout season came in 1963 as Maloney got the first of two 20-win seasons as he posted a 23-7 record with a .277 ERA and struck out 265 batters in 250.1 innings while walking 88.

The performance would have won a Cy Young but it just so happened that the Los Angeles Dodgers’ Sandy Koufax was 25-5 and led the majors with 306 strikeouts as Maloney finished second.

Koufax was not only the Cy Young winner but the NL Most Valuable Player.

Maloney went 15-10 the next season with 214 strikeouts and the got his second 20-win season in 1965 as he was 20-9 with 244 strikeouts and had a 2.54 ERA. Teammate Sammy Ellis won 23 games.

Over the next four years, Maloney had records of 16-8, 15-11, 16-10 and 12-5. Besides seven straight seasons with double-digit wins, Maloney had four straight seasons for more than 200 strikeouts and he had 181 in 1968.

Maloney was clocked at 100 miles an hour during the era when the pitch was timed as it crossed the plate as opposed to today’s game when pitcher’s fastball is measured on its exit velocity as it leaves the hand.

There was a report that Maloney was once clocked at 110 miles an hour, but he shrugged it off.

“I don’t know anything about that. That might be some fake news,” said Maloney with a chuckle.

“I never knew how fast I threw. I knew most major league hitters could hit a fastball. If they knew a fastball is coming, you better put it in a good spot. As soon as I got a ball or two balls on a guy, he knew he was going to get a fastball. Whether it was (Willie) Mays or (Hank) Aaron or anybody, I would just challenge them. A lot of times I just threw the ball right by them. So, I knew I had the speed but I don’t know how hard I threw but I’d say it had to be around 100 and I was like that for nine innings.”

While Maloney saw future Hall of Fame hitters on a regular basis and had good success getting them out, there was one good hitter who gave him problems that left him frustrated to the point he took drastic measures to finally get him out.

“Rusty Staub used to hit me quite well and I couldn’t get him out. We were flying down to the Astrodome in Houston and I told (catcher Johnny) Edwards, ‘I’m going to tell Staub what’s coming and see what happens. Can’t do any worse,’” recalled Maloney.

“So, I started the game and I got out there on the mound and he came up there to hit and I walked off the mound to the Astroturf and I looked at him and said, ‘Fastball.’ I went back and threw him a fastball and he took it. Then I went back down and said ‘Curveball,’ and I threw him a curve and it was a ball or something like that. And then I did it one more time and said ‘Fastball’ and he hit a ground ball and was out and after that I didn’t have much problem with him.”

Because of his Achilles injury, the sizzle of his fastball now merely fizzled.

Maloney appeared in just seven games in 1970 when the Reds won the NL pennant and was 0-1. He was traded to the California Angels in 1971 and was in only 13 games and went 0-3 and elected to retire.

Cincinnati enshrined Maloney into the franchise’s Hall of Fame just two years later in 1963. His final glorious moment with the Reds wasn’t celebrated as it is today. It seemed more like taking a trip to the grocery store.

“(Reds’ owner) Bob Castellini and that family deserve a championship. That guy is a really good fan and he’s a community guy. He tries to do the best he can,” said Maloney.

“(Former Reds’ general manager) Bob Howsam and I go into it. He believed there was nothing wrong with me when I ruptured my Achilles tendon. He told me I had no pain tolerance. He told me I had to learn to pitch with pain because Bob Gibson pitched with pain. (Howsam) came over from St. Louis where he was the general manger. I had a lot of resentment built up against (Howsam).

“When I left the Reds, I came home from 1972 until when Bob Castellini bought the Reds, I never heard from the Reds. Not one time. They told me I was inducted into the (team’s) Hall of Fame and they mailed my plaque to me. This was 1973. They said you got voted into the Hall of Fame. I never heard one thing until Bob Castellini bought the ball club and he called and he’s invited me and my wife to spring training every year for a week to be with the team and during the winter meetings to meet with the silent partners. And that’s the kind of guy he is. I do anything for that guy if I work for him or if I was playing under that guy. He’s a real trooper. He’s a real businessman and he’s got a wonderful family.”

But this shameful treatment couldn’t erase the magnitude of Maloney’s accomplishments.

He finished with 134 wins and only 84 losses with three of those coming with the Angels. He had 1,605 career strikeouts with 1,592 coming with the Reds, a team record that still stands today.

He had a career ERA of 3.19 and a microscopic 1.259 WHIP. In 1,849 innings pitched, he gave up only 138 home runs.

Eppa Rixey — a member of the Reds and baseball’s Hall of Fames — is the all-time victory leader for Cincinnati with 179 but his 13 seasons produced 148 losses.

Maloney had 74 complete games in his career including 30 shutouts. His five one-hitters are tied for the third most in history along with Bert Blyleven, Jim Palmer, Tom Seaver, Don Sutton, Dave Steib and Phil Douglas.

All are in the Hall of Fame except Steib, Douglas and Maloney.

If not for the Reds desire to make Maloney focus on pitching, Maloney could have easily been drafted as a shortstop. Half of the 16 teams in the major leagues wanted Maloney as an infielder while the other eight wanted him as a pitcher.

With his hitting background, it wasn’t surprising that Maloney was a good hitting pitcher. He had a career batting average of .201 with seven home runs, 21 doubles and he piled up 53 runs batted in as he collected 126 career hits.

But Maloney wasn’t just a good all-around baseball player. While baseball was his first and true love, he was also a standout in football and basketball.

After the baseball season his senior year, it was just two days after graduation when all 16 teams began visiting the Maloney home. Half of the teams sought him as an infielder and half as a pitcher. Maloney was a little surprised at the interest in him as a pitcher.

“I hadn’t throw more than 25 innings when I signed a contract with the Reds,” said Maloney. “These guys today, they’ve pitched most of their careers in high school and little league and then they send them to Dayton or some place and they only let them throw 40 pitches.

“I had five or six complete games in Topeka and I won six of seven. Nobody had a pitch count on me. I you got your ears pinned back, they took you out and you’d get ready for your next start. I think it’s bad for the pitching. I had a major league contract so they couldn’t play me below Class B ball,” said Maloney.

It was 61 years ago on April 1, 1959, that Maloney signed a major league contract with the Reds. The three-year deal was for $100,000 and Maloney could not pitch below Class AA level since it was a major league contract.

“I got some money to sign. I would have been a first-round draft,” said Maloney noting the MLB draft didn’t begin until 1965.

Maloney didn’t sign right out of high school. He spent a semester at the University of California and then transferred back home to Fresno City College. It was at Fresno where Reds’ west coast scout Bobby Maddix saw Maloney pitch and immediately made it his mission to sign the 19-year-old pitcher.

“The scouts would come in and bid. St. Louis would come in and say, ‘We can give the boy $40,000.’ My dad (Earl) handled everything. I would have signed for a Hershey bar. My dad said, ‘Naw, he’s worth more money.’ And they’d keep leaving the house. Another guy comes in and says ‘We can only give him $30,000’ and my dad said ‘St. Louis offered him $50,000 so you’re wasting your time here.’ (Earl Maloney’s friend George Bryson) announced the Fresno Cardinals games. He said the Reds really wanted me so he was instrumental in the deal.”

“I had all these scholarships to go to these schools and dad ran all the scouts out of the house and said ‘he’s going to Cal.’ I went up to Berkeley for a semester and then I came back to Fresno City College and I started to play there. I was playing shortstop and they needed a pitcher so I pitched and threw a no-hitter. Bobby Maddix was the Reds’ West Coast scout and nobody knew he was in town and he came in and said ‘we’ve got the money and we want to sign him and we want to get him out.’ That was on April 1, 1959. So, I signed a contract.”

Maloney will turn 80 on June 2. He spends a lot of his time fishing but he has been attending the Reds’ Fantasy Camp for the past 37 years.

He and former Reds’ Big Red Machine era pitching ace Jack Billingham managed the teams at the Fantasy Camp.

“We’re the oldest guys in camp. We run the ball club and we do a little instruction. The only thing I don’t do that I did until I was 70 years old, I used to throw an inning or maybe three innings against the campers. When I turned 70 I said that’s it. I’m not going out on that mound and get killed. I know my limits. I can’t throw anyway. My arm is all shot. It’s a great time. There were a 150 guys this year. They had a wonderful time. It’s a wonderful time. I’m the only guy from the 60s clubs. Billingham and I keep things stirred up. It’s a good time,” said Maloney.

Just like Jim Maloney’s career, Fantasy Camp isn’t perfect.

It’s just great.