Bob Leith: Strange but true — The last thoughts of a dying father

Published 12:00 am Sunday, June 19, 2022

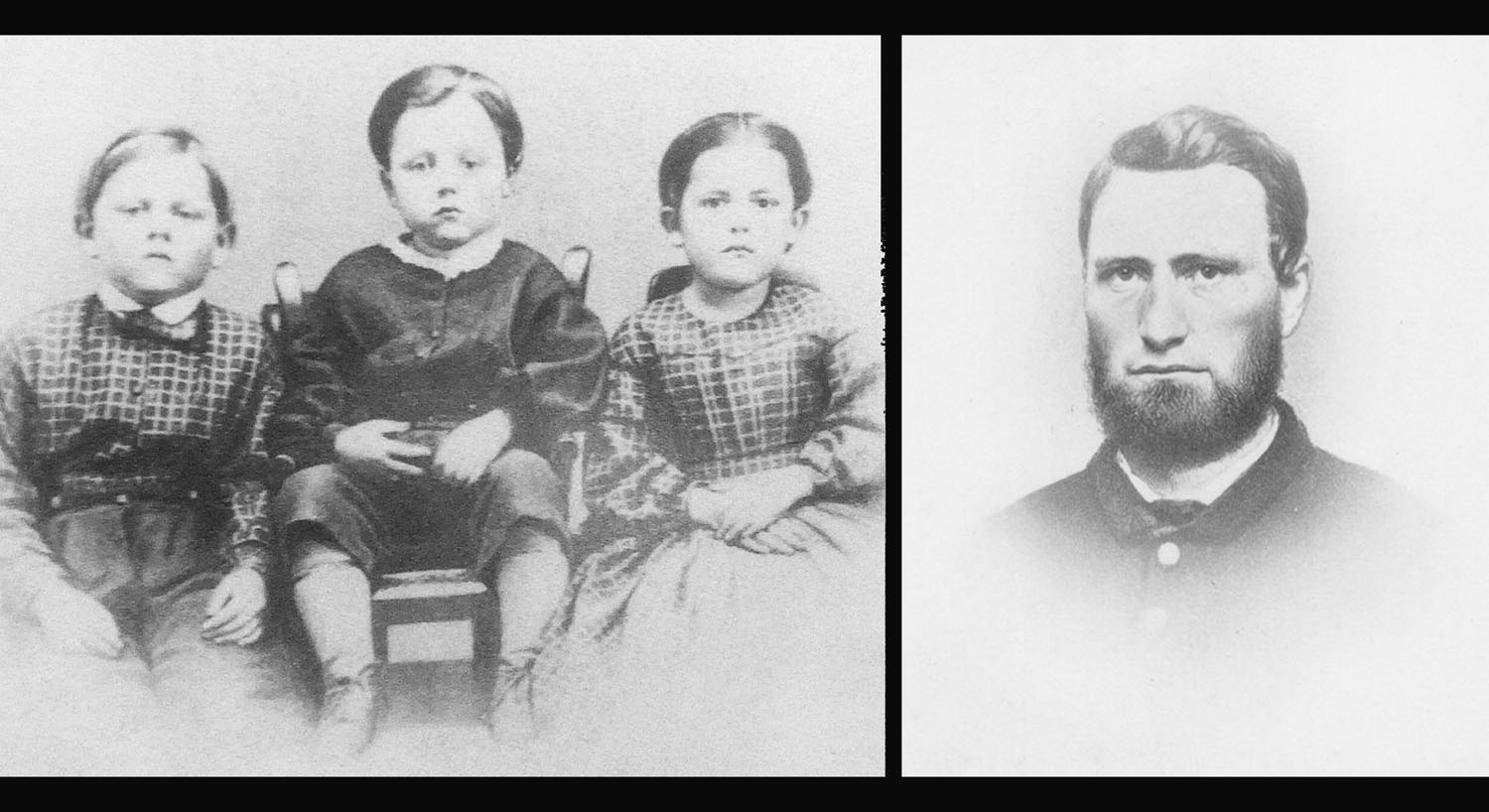

- LEFT: This ambrotype of the children of Sgt. Amos Humiston was used to identify their father after his death. RIGHT: Sgt. Amos Humiston was a Union soldier killed in the Battle of Gettysburg on July 1, 1863. (National Park Service photos)

By BOB LEITH

For The Ironton Tribune

After his successful victory at Chancellorsville in May of 1863, Robert E. Lee planned to invade the North a second time.

As the Army of Northern Virginia entered Pennsylvania, it was being followed by the Union’s Army of the Potomac, led by a new commander. The two armies moved toward the small town of Gettysburg in Adams County, Pennsylvania.

Neither general wanted to fight a battle around this town of 2,400. Lee, thinking military success on northern soil might lead to an end to the war, led 75,000 southern troops. Opposing him were 90,000 troops led by George G. Meade.

A Confederate infantry brigade, in search of much-needed shoes, ran into two Union cavalry brigades west of Gettysburg. This incident led to the Civil War’s most famous battle and the greatest battle ever fought in the western hemisphere.

After three days of battle, Lee would begin to retreat to Virginia. History would record the three-day battle of Gettysburg as the turning point of the Civil War. Never again after this battle would Lee be strong enough to mount a major military offensive.

Between July 1-3, 1863, the Army of the Potomac suffered 23,049 casualties. Lee, who would consider resigning his position after the defeat, had 28,063. Of the 51,112 total casualties of both armies combined, 7,058 were battle deaths.

This article will cite one such death of the total 7,058. The United States had never seen such carnage!

Students of the American Civil War immediately recognize the names of Lee, Meade, Hancock, Stuart, Ewell, Hood, the deceased Jackson, Longstreet and Armistead. Pickett’s Charge and President Abraham Lincoln’s two-minute address add additional fame to the Gettysburg story.

More than 165,000 soldiers (both sides combined) were at Gettysburg. The 2,400 residents of the town and students at Gettysburg College and the Lutheran Seminary would be directly or indirectly affected by this battle site.

Discounting the dead, soldiers who survived, residents of the town, college students and Gettysburg’s Children, probably all had stories to tell about those three days in July of 1863.

Many stories have survived. But how many of the unknowns do we know?

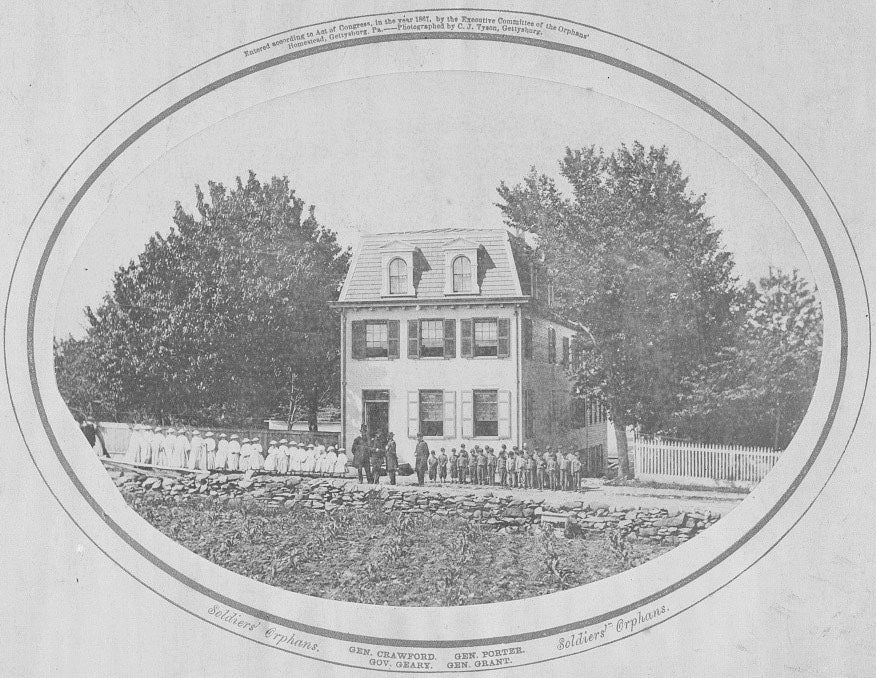

The National Homestead at Gettysburg was the Gettysburg Orphanage and a widows home. The family of Sgt. Amos Humsiton resided there until his widow, Phylinda Humiston, remarried and they moved to Massachusetts. (Library of Congress print collection)

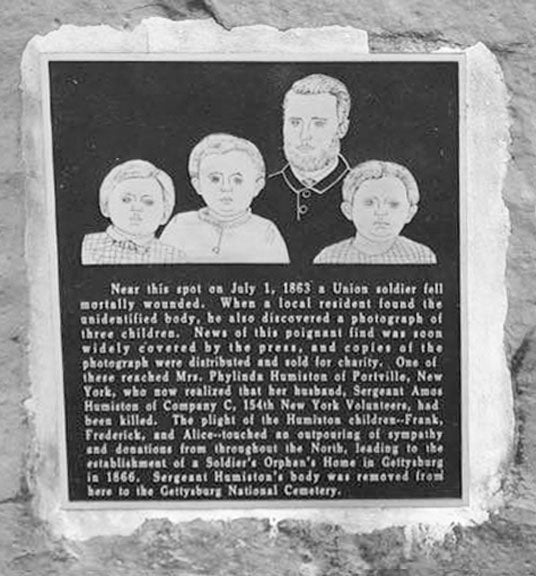

A Union burial detail discovered a dead Union soldier on Stratton Street in the town of Gettysburg. The soldier looked as if he were frozen, but his eyes were fixed upon an object he was holding in his hand. He was holding an ambrotype (picture in 1863) of three small children. The picture was the last thing seen by the unknown Union soldier before he died. Searching his person and the area around him rendered no identification. The unknown Union soldier was buried in a marked grave in a lot owned by Judge S.R. Russell of Gettysburg. A member of the burial detail kept the picture and word began to spread about the unknown soldier.

Dr. John F. Bournes, of Philadelphia, was touched by the devotion of this soldier-father. He decided to try to locate the soldier’s family despite being told many times that such a project would be futile.

Bournes borrowed the picture and had thousands of cartes de visite made and circulated them throughout the north. Many newspapers printed the story of the unknown soldier. Letters from mothers, wives, sisters and other family members flooded Dr. Bournes’ mail. He sent each a copy of the ambrotype. The mystery remained unsolved from July-November 1863.

In November 1863, a letter came to Bournes from Portville, New York. A soldier’s wife had seen a story about the ambrotype in the American Presbyterian published in Philadelphia. Only one copy of the newspaper had arrived in Portville.

Phylinda Humiston, of Portville, had not heard from her husband since the Battle of Gettysburg. Sadly, Phylinda learned she was a widow and her three children, Franklin, Frederick and Alice, now had no father.

Due to the determination of Bournes, the soldier was identified as Sgt. Amos Humiston, of Company C, of the 154th New York Infantry Volunteers. Humiston was a hero throughout the North and was said to represent the common soldiers in the Union Army. Humiston’s story has faded into obscurity with the passage of time.

Who was Amos Humiston and what was his involvement in the Civil War prior to July 1, 1863?

He was born in 1830 in Oswego, New York. He married Phylinda Smith on July 4, 1854. They had the three children seen in the ambrotype.

Amos was a harness maker by trade and was said to be a quiet citizen, a kind neighbor and devotedly attached to his family.

When the Civil War began, Amos wanted to enlist, but worried about leaving his family. When President Lincoln called for 300,000 volunteers, Amos Humiston answered the call, only after the people of Portville, New York, promised to look after his family. He enlisted on July 26, 1862, in Portville for three years in the 154th New York.

Amos Humiston and his regiment went to Washington and northern Virginia where they spent seven months without ever participating in a battle. On Jan. 25, 1863, Amos was promoted to sergeant.

Sgt. Humiston got a real taste of war when his New York regiment, as part of the 11th corps, was brutally beaten and, embarrassed by Stonewall Jackson’s famous flank attack at Chancellorsville on May 2, 1863. After this battle, Lee would decide to invade the North and the two armies would clash for three days at Gettysburg.

On Day 1 or July 1, 1863, Sgt. Humiston and his brigade were on Cemetery Hill watching two divisions of the 11th corps retreat, after being attacked by Jubal Early’s Confederate division.

Humiston’s brigade was ordered to form a Rearguard to cover the Union retreat. The Union brigade marched through the town of Gettysburg to its northern boundary.

The National Homestead at Gettysburg was the Gettysburg Orphanage and a widows home. The family of Sgt. Amos Humsiton resided there until his widow, Phylinda Humiston, remarried and they moved to Massachusetts. (Library of Congress print collection)

Three Union regiments, of which Humiston’s was one, lined up behind a fence. Eight regiments attacked the ill-formed Union line, thus outflanking and almost surrounding the three Union regiments. The Union regiments had to run through the town and most of them were shot or captured. Day 1 or July 1, 1863, clearly belonged to the Confederacy.

Amos Humiston’s 154th New York was decimated by Early’s forces. At evening roll call, only 18 members of the 154th New York were present. The regiment had lost over 200 men. Sgt.

Amos Humiston was reported as missing. He was continued to be reported as missing until his identity was solved by the efforts of Dr. Bournes in November.

Bournes had planned to sell photographs of the Humiston children and give the money to their mother for their support. In January of 1864, he traveled to Portville, New York, to return the original ambrotype to Phylinda Humiston.

While there, Bournes persuaded her to establish the Soldiers’ Orphans’ Home in Gettysburg in 1866. This orphanage was in operation from 1866 until 1877, when it was closed due to two major scandals.

Phylinda Humiston was the first matron of the orphanage. She and her children lived at the orphanage on Baltimore Street until 1869. The woman who followed Mrs. Humiston was Rosa Carmichael. Rosa did not meet the orphanage’s financial obligations and she was convicted of assaulting the orphans.

In October of 1869, Phylinda married Asa Barnes and they moved to Massachusetts. Left in Gettysburg on Cemetery Hill was Sgt. Amos Humiston. He was reburied in Grave No. 14, Row B, in the New York section in the National Cemetery. For a while, Sgt. Humiston was special.

Bob Leith is a retired history professor from Ohio University Southern and The University of Rio Grande.