VETERANS DAY: Packing parachutes in the midst of WWII

Published 12:00 am Friday, November 11, 2022

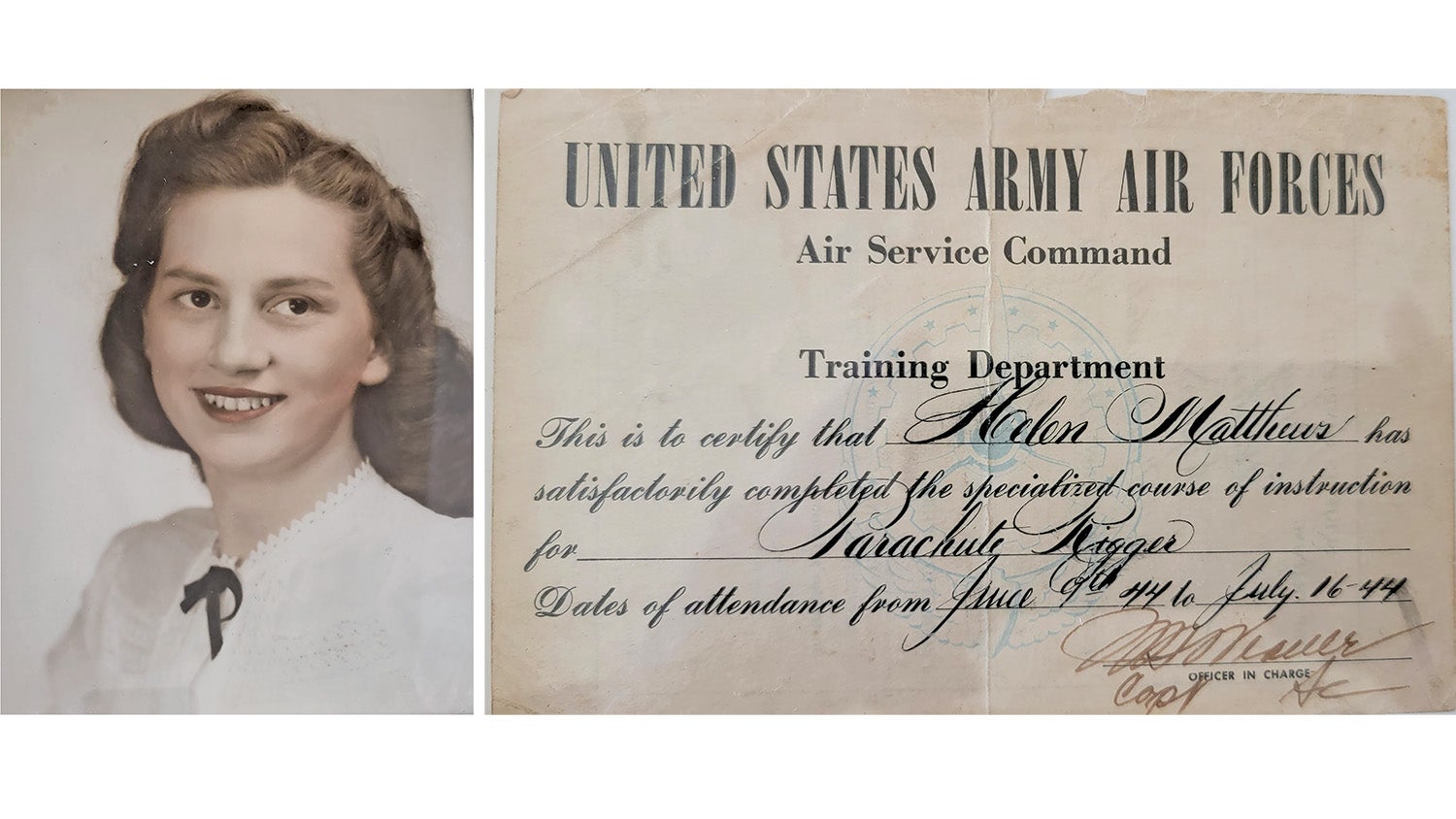

- LEFT: In 1944, young Helen Matthews left Lawrence County at age 16 to go to Dayton to pack parachutes for the U.S. Army Air Forces. (Submitted Photo) RIGHT: Helen Matthews’ certification from the U.S. Army she passed her class on parachute rigging. (Photo submitted)

Millhouse left school at 16 to work on U.S. Army Air Forces Base

SOUTH POINT — An army is more than just soldiers.

There are thousands whose job it is to supply those soldiers with everything from boots to tanks.

During World War II, Helen Matthews Millhouse was one of the women who worked in an industrial setting rigging parachutes.

It was a matter of patriotism and pragmatism that took Helen from Hanging Rock to Dayton in 1944 to work on the U.S. Army Air Forces base. Her job was to pack parachutes and repair harnesses.

“I wanted to help my family and I needed a job to do that. And I also wanted to help our county in every way I could,” Helen said.

Her parents had divorced when she was five years old and her grandparents took her into their home. Her grandfather was often sick and couldn’t keep a steady job and that left the family in a precarious situation.

When Helen was 16, a speaker came to the school to talk to the older students about getting jobs as civilian workers to help out the war effort.

“I went in and talked to the principal,” Helen said. “I told him ‘I need to get a job. I need to help my family.’ I knew he wouldn’t like me to leave school right then but I was going to quit school and I hoped he would agree with me. And he did.”

Being a war time situation, she was allowed to go, so she and a neighborhood friend, who was part of a big family, became civilian laborers for the military.

“We signed up together and took a train to Dayton,” Helen said.

She said she wasn’t afraid of moving to a big city or the job.

“If I wanted to do something, I made my mind up ahead of time whether it was smart to do it or not,” she said. “If I knew something was going to get me in trouble, I didn’t do it.”

At the Fairfield Air Service Command, now known as Wright-Patterson Air Force base, Helen was one of 100 women who worked at long tables all day long.

“You were actually making the parachute packs,” she said. She doesn’t recall how long the shifts were. “I just worked as long as they wanted me to. If we were caught up on parachutes, I had them put me back on another line. I just did whatever they told us to do.”

She lived on the base in a house with 16 women.

“It was a big house,” she recalled. “We would just walk over to the field to work. We wore uniforms.”

She started off as a laborer and was soon upgraded to general mechanic’s helper.

“I was doing everything I could. Everybody was, all over the country,” she said. “Everyone I met was doing their best to help out.”

She remembers supervisors continually walking around to make sure that every ‘chute was done properly, because it was a matter of life and death.

“They made it very plain that it could be a guy’s death if you didn’t do it right,” she said. “And a person would have to be nuts not to understand that.”

There was one mystery on the base and Helen has never solved it.

There was a building, next to the one she worked in, that was apparently deemed secret and everyone was told to stay away from it.

“It was so close you could touch it from the one we worked in. We were told not to go around that building and not to look in the windows of that building,” she recalled. “If we did, we would be fired. So, I didn’t question it. I just stayed away.”

There were all kinds of weird stories about the building and the other young people would speculate, but not Helen.

“Anything that would get me in trouble, I stayed away from it,” she said. “So I never did know what it was for sure.”

On her free weekends, Helen would ride the bus from Dayton back home to check on her grandparents. Helen’s uncle used to check on them but was drafted into the military.

“I had to stand up the whole way home on the Greyhound bus,” Helen said. “It was so crowded. No one had cars. There just wasn’t anyone to check on her. I’d come home and make sure she was alright and she if she needed money and made sure she had enough food,” Helen said.

Between standing on the line all day and riding standing up on the bus, Helen began to have issues with her legs.

“I had a nurse taking care of me,” she said. “The nurse kept wondering what to do. Eventually, she said I would have to quit. So, my sister and aunt came down to make sure I could make the trip home.”

She said that so many men had been drafted into the military that there were entire neighborhoods that were just women and children.

“Nobody had any men in the house. They were all in the service, unless they had something wrong with them,” Helen said.

During World War II, everything was rationed and every person was issued a booklet with the items they could buy. And if a person had a ticket for something they didn’t use, they would often get the item and then trade it for what they did want.

For example, cigarettes were rationed. Since Helen didn’t smoke, she would have extra tickets.

“When Arthur and I were dating, my sister and I would buy him two or three packs of cigarettes and then we would give them to him if he would buy us two or three candy bars,” Helen said. “Everybody was trying to get by.”

Arthur had just gotten out of the U.S. Army after being stationed in France and England.

He was a medic and part of Operation Overlord, which was the Allied Forces invasion of Normandy, France.

“He and another guy would go out and get wounded soldiers and bring them back to the doctor’s tent,” Helen said. “He told me that one day, he was in an ambulance and he just had a bad feeling that he needed to get out of the ambulance and get away from it. He kept on feeling so eventually, he just jumped out. And about a minute after he jumped, a bomb hit that ambulance.”

Arthur didn’t talk much about his war experiences because it gave him nightmares. He was hospitalized for a long time for shell shock.

“We tried to never talk about it, he was always bothered by it,” Helen said. “When he got home, the doctor told him that he would never be able to work because it would be too much for him. But he worked all the time. You just couldn’t stop him from working.”

After they got married, they lived in South Point and Arthur worked at Dayton Malleable for 37 years.

Helen said they had a good life together.

“He was really good man. He was a good father to the kids, a good husband to me,” Helen said. “He was just a good person.”

Helen said that when Arthur got to feeling bad, they would go out for rides.

“We would just put the kids in the car and go somewhere,” she said.

Helen was a stay-at-home mother and raised their four children.

“I knew I couldn’t work and raise the kids both. I had to choose between one or the other,” she said. “So, that’s what I did.”