HISTORY LESSON — Bob Leith: ‘Bury my heart at Wounded Knee’

Published 12:00 am Tuesday, February 21, 2023

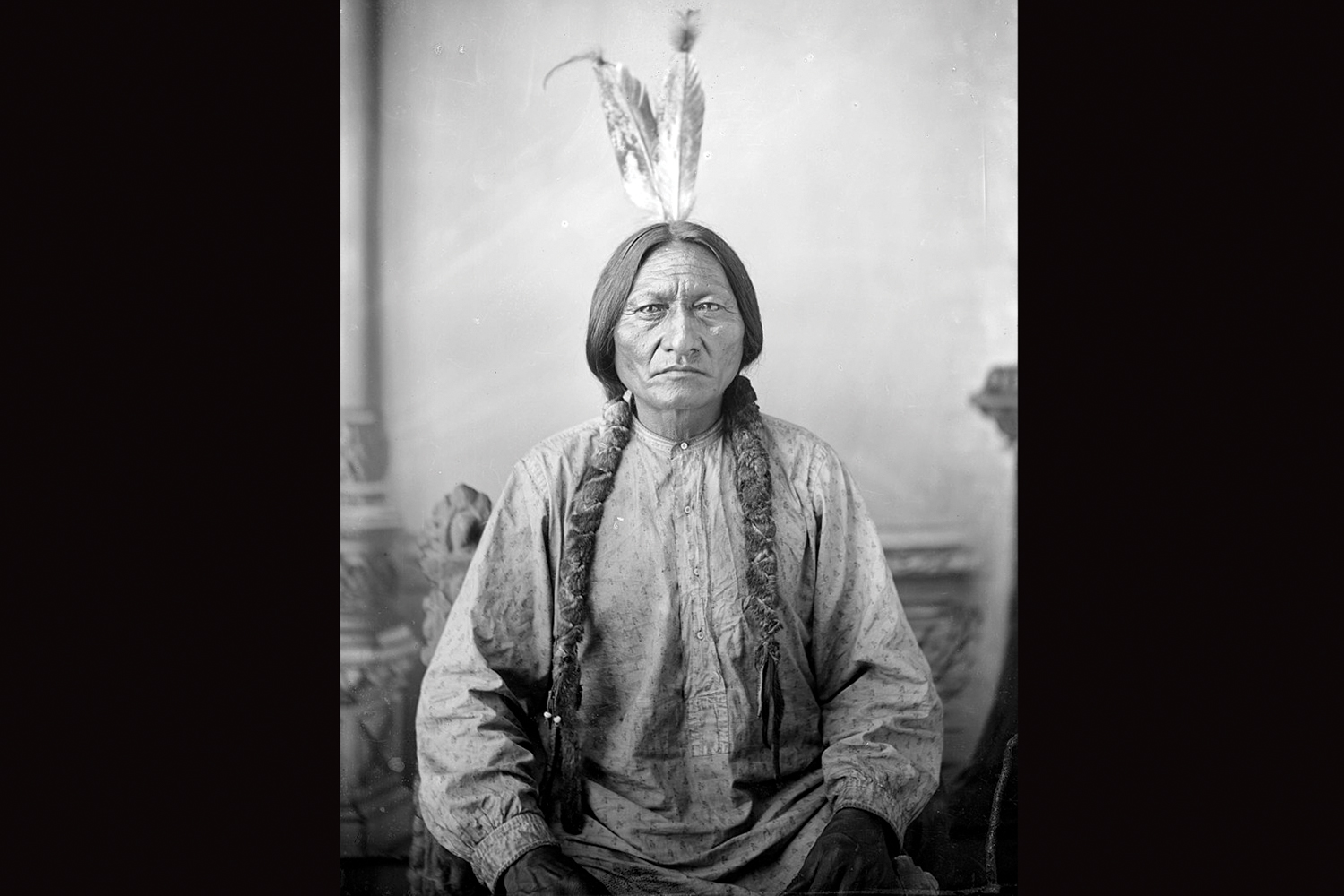

- Sitting Bull, photographed in 1883. (Public domain)

At the Battle of the Little Big Horn in 1876, Sitting Bull, using his vision that came in 1875, performed as a medicine man to prepare the Sioux for the important battle.

After the battle, in which the Sioux decimated Custer’s army, Sitting Bull and many Sioux went to the “Land of the Grandmother” – Canada.

On July 19, 1881, Sitting Bull and 186 Sioux followers left the safety of Canada and rode into Fort Buford, North Dakota.

He was arrested as a prisoner and held at Fort Randall, South Dakota, for two years.

Afterwards, Sitting Bull lived at Standing Rock Reservation in South Dakota in his log cabin.

To get Sitting Bull away from South Dakota and take more of Sioux lands, the U.S. secretary of the Interior authorized a tour of 15 American cities for Sitting Bull and, in 1885, “Buffalo Bill” Cody talked him into joining his Wild West Show.

In 1887, Cody tried to get Sitting Bull to go to Europe with the show, but Sitting Bull said he should stay at Standing Rock Reservation to prohibit taking of more Sioux lands.

In the fall of 1890, the federal government had broken Standing Rock into “fragmented islands.”

A Minneconjou from another reservation came to visit Sitting Bull.

This visit would change the history of the American West.

A depiction of the Ghost Dance, by Amédée Forestier, originally published in The Illustrated London News in 1891. (Public domain)

The native’s name was Kicking Bear.

He told Sitting Bull about a “Piaute Messiah” named Wovoka who had founded the religion associated with the Ghost Dance.

Kicking Bear and his brother-in-law, Short Bull, had traveled to see and hear the “Piaute Messiah” at the Pyramid Lake, Nevada, but he was not there.

He had gone to Walker Lake Agency where hundreds of natives of different tribes had gathered to see this Messiah.

The Piautes (“Fish Eaters”) told Kicking Bear and Short Bull that Jesus Christ had returned to earth in the form of a native.

A native appeared and spoke to the gathering.

He appeared to be a gentleman, quite husky, and in his early 30s. He was the son of a Piaute prophet.

Wovoka claimed he had died and visited God in heaven.

He told them he would teach them to dance a dance and he wanted them to seriously perform it. This dance was the Ghost Dance.

They were to return to their tribes and dance this dance for five consecutive days.

Those assembled began singing and dancing until late at night.

Kicking Bear went to see if this messiah had the scars of the crucifixion upon his body.

He saw a scar on Wovoka’s wrist, but could not see his feet for the moccasins he wore.

Wovoka’s message told that, in the forthcoming spring, the earth would be covered with a heavy layer of new soil, which would bury and suffocate all white men.

This new layer of earth would be covered with sweetgrass and cool running water.

All dead buffalo and horses would return to life.

The natives who faithfully danced the Ghost Dance would be suspended in the air while the new wave of earth buried all whites.

After the new wave of earth had settled, all dead natives would come back to life.

Kicking Bear brought the Ghost Dance to Cheyenne River and Short Bull introduced it at the Rosebud Agency.

Sitting Bull listened to the two visitors, but felt it impossible for the dead to return to life.

He told them he did not care if his Sioux followers danced.

Kicking Bear said that the dancers he saw wore “Ghost Shirts” with magic symbols on them. He told Sitting Bull that the shirts would ward off white men’s bullets.

Kicking Bear taught the Sioux at Standing Rock Reservation in South Dakota the Ghost Dance and told them of Wovoka’s message and advice.

The dance began to spread like a prairie fire!

By fall, the government had heard of the messiah’s message, the Ghost Dance and the Ghost Shirts.

The United States government in the distant east announced, “Stop the Ghost Dancing!”

In his message at Walker Lake Agency, Wovoka had said, “You must not fight. Do no harm to anyone. Do right always!”

Thus, the Piaute Messiah preached nonviolence and brotherly love, but the government officials were ordering soldiers to stop the Ghost Dance.

Upon hearing of the government interference, natives began to wander off their reservations.

Three thousand “hostiles” followed Kicking Bear and Short Bull to a location called the “stronghold.”

Natives throughout the Great Plains, the southwest and the far west adopted the dance and its Ghost Shirts.

In October 1890, a native agent notified the commissioner of Indian Affairs that the person behind the Ghost Dancing at Standing Rock Agency was Sitting Bull. This was a blatant lie.

By mid-November 1890, Ghost Dancing had become so important that native children would not attend school, natives did not frequent the trading stores and they quit tending their crops.

On Nov. 20, 1890, a list of Ghost Dance leaders was sent to Chicago to Nelson Miles, the army officer who had affected the surrender of Geronimo.

He saw Sitting Bull’s name and assumed he was the main inspiration for the Ghost Dancing in South Dakota.

The federal government sent “Buffalo Bill” Cody to ask Sitting Bull to travel to Chicago for a conference with Miles.

The plan was to get Sitting Bull to Chicago and then place him in prison.

The native agent would not let Cody see or talk to Sitting Bull.

On Dec. 12, 1890, 43 native agency policemen surrounded Sitting Bull’s log cabin. Three miles away a backup unit of cavalry waited. When told he was to be arrested, Sitting Bull asked to put on his clothes. When Lt. Bull Head brought Sitting Bull outside, several Ghost Dancers had gathered.

The Ghost Dancers said they would not allow Sitting Bull to be arrested.

A Ghost Dancer, Catch-the-Bear, wounded Lt. Bull Head. Lt. Bull Head wounded Sitting Bull as he fell.

Another agency policeman, Sgt. Red Tomahawk, then shot Sitting Bull in the head.

Only the cavalry, hearing the shooting, saved the 43 native police from being slaughtered.

Sitting Bull was recognized by the Sioux people as their greatest leader.

He had prepared them prior to the Battle of the Little Big Horn.

The United States government lied to him many times.

How ironic it was that the staunchest of all the Sioux “nonprogressives” was killed by his own people!

Had it not been for Wovoka’s message, the Sioux might have waged war upon the whites.

They believed the whites would all die in the spring.

Another Sioux leader, Big Foot, heard that Sitting Bull had been killed and that he also was to be arrested.

Big Foot decided to lead his people to the Pine Ridge Agency where the last great leader of the Sioux people, Red Cloud, might protect them and their dancing.

Big Foot had pneumonia and was bleeding profusely.

On Dec. 28, 1890, Big Foot’s band saw four troops of cavalry coming toward them.

Big Foot had a white flag placed over his wagon.

Maj. Whitside told Big Foot that he had orders to take him and his people to a camp on Wounded Knee Creek.

Big Foot told the major he wanted to go to the Pine Ridge Agency instead.

On Dec. 28, 1890, the natives reached Chankpe Opi Wakpala – the Wounded Knee Creek.

There were 120 men and 230 women and children in Big Foot’s band. Whitside would try to disarm them the next morning – Dec. 29, 1890.

Whitside gave the natives rations and provided tents for them.

He had a stove put in Big Foot’s tent and sent a surgeon to examine him.

It was December, it was very cold and the natives were around 30 miles from their destination – Pine Ridge Reservation.

“Buffalo Bill” Cody, Capt. Baldwin, Gen. Nelson A. Miles, Capt. Moss and others on horseback, on battlefield of Wounded Knee. (Public domain)

To make sure no natives escaped in the darkness, two troops of cavalry were stationed around the natives’ tepees and tents.

Two big Hotchkiss guns were placed on a rise overlooking the encampment. Their effective range was two miles.

Later that night, the rest of the 7th Cavalry arrived under the command of James W. Forsyth. Forsyth told Whitside he had orders to take all of Big Foot’s band to the railroad to be placed in a military prison in Omaha.

Forsyth placed two more Hotchkiss guns on elevated ground.

His men began drinking to celebrate finding Big Foot’s band. Drunken soldiers knew that some of these natives had helped defeat Custer 14 years ago.

On the morning of Dec. 19, 1890, all male natives were to report to the center of the encampment.

Upon arriving, the natives were to stack all weapons and ammunition near the soldiers.

When few weapons were produced, the soldiers searched the tepees and caused much destruction.

Two natives, wrapped in blankets, concealed rifles.

A native named Black Coyote showed his new rifle. Years later, it was discovered that Black Coyote was deaf and did not hear the soldiers’ orders.

Some soldiers wrestled with Black Coyote. He did not know why, since he bought the rifle with his own money.

Someone, somewhere fired a single shot. We will never know who fired that shot!

The soldiers, some feeling the effects of alcohol, panicked and fired upon the natives.

The four Hotchkiss guns erupted on the natives. Some natives tried to run, but couldn’t escape the Hotchkiss guns.

When the massacre was over on Dec. 29, 1890, at Wounded Knee Creek, 153 natives were dead.

Some wounded Sioux crawled away and died later. The army estimated that 300 of the original 350 members of Big Foot’s band died.

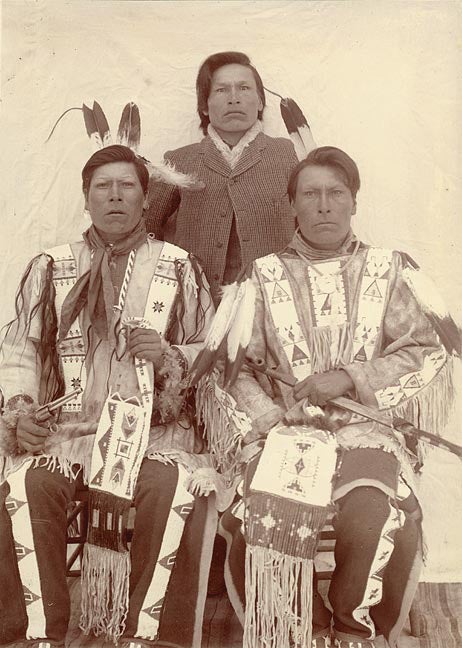

Brothers and Wounded Knee survivors, from left, White Lance, Joseph Horn Cloud and Dewey Beard, Wounded Knee survivors; Miniconjou Lakota. (Public domain)

The soldiers lost 25 dead and 39 wounded. The surviving natives were loaded into army wagons, but the dead were left lying in the snow because a blizzard was coming.

A burial party would come back and find the dead natives frozen.

After dark that day, 47 women and children, along with four Sioux men, reached Pine Ridge.

All buildings were occupied and they were placed in the Episcopal Church after hay had been put on the floor.

At the Pine Ridge Agency Church, Christmas decorations still remained.

Above the pulpit, a banner read, “Peace on Earth, Good Will to Men.”

Three days after the massacre, a burial party returned to Wounded Knee and buried the frozen natives in an open trench. Members of the burial party received two dollars per body.

The whole decade from 1880-1890 had been very unkind to the Dakota Sioux.

There were droughts. Congress cut the rations to the reservations. Many epidemics took Sioux lives.

The federal government wanted to decrease reservation lands, but Sitting Bull had stood in its way

Now, a massacre ended the Indian Wars in the west. Conflict had occurred much earlier at Jamestown in 1607 and Wounded Knee was the natives’ “last stand.”

And Wovoka? During a fever, he dreamed he visited heaven. The Great Spirit taught him some songs and a dance. He, while there, learned the doctrines of the Ghost Dance religion.

Wovoka was adopted when a boy by David Wilson and was given the name Jack Wilson.

The Wilsons taught him about Christ and the Bible. Wovoka died in 1932.

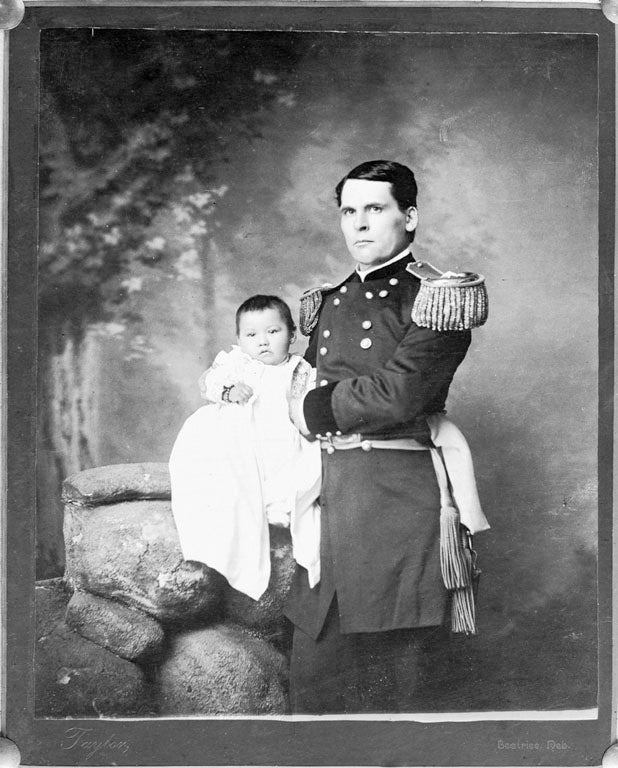

Zintkála Nuni, aka Lost Bird, at four months old in 1890, held by her adoptive father, General Leonard Colby. ( Public domain)

When the burial party came to Wounded Knee, a four-month-old baby named Lost Bird was found alive in her mother’s frozen blood.

Gen. Leonard and his wife raised her as Mary Write Colby.

She died in poverty in 1919 at age 29. She was one of over 60,000 Sioux children “handed out as presents to Christian families” since 1890.

In 1991, Lost Bird went home to South Dakota.

Never accepted by the community, she worked as a musician in “Buffalo Bill’s” Wild West Show. Lost Bird was taken home to Wounded Knee by a horse-drawn wagon after being exhumed.

After the Wounded Knee Massacre, only the great chief Red Cloud was left. He said, “They made us many promises, more than I can remember, but they never kept but one: They promised to take our land, and they took it.”

— Bob Leith is a retired history professor from Ohio University Southern and The University of Rio Grande.