The arc to Arcturus

Published 12:00 am Saturday, April 29, 2023

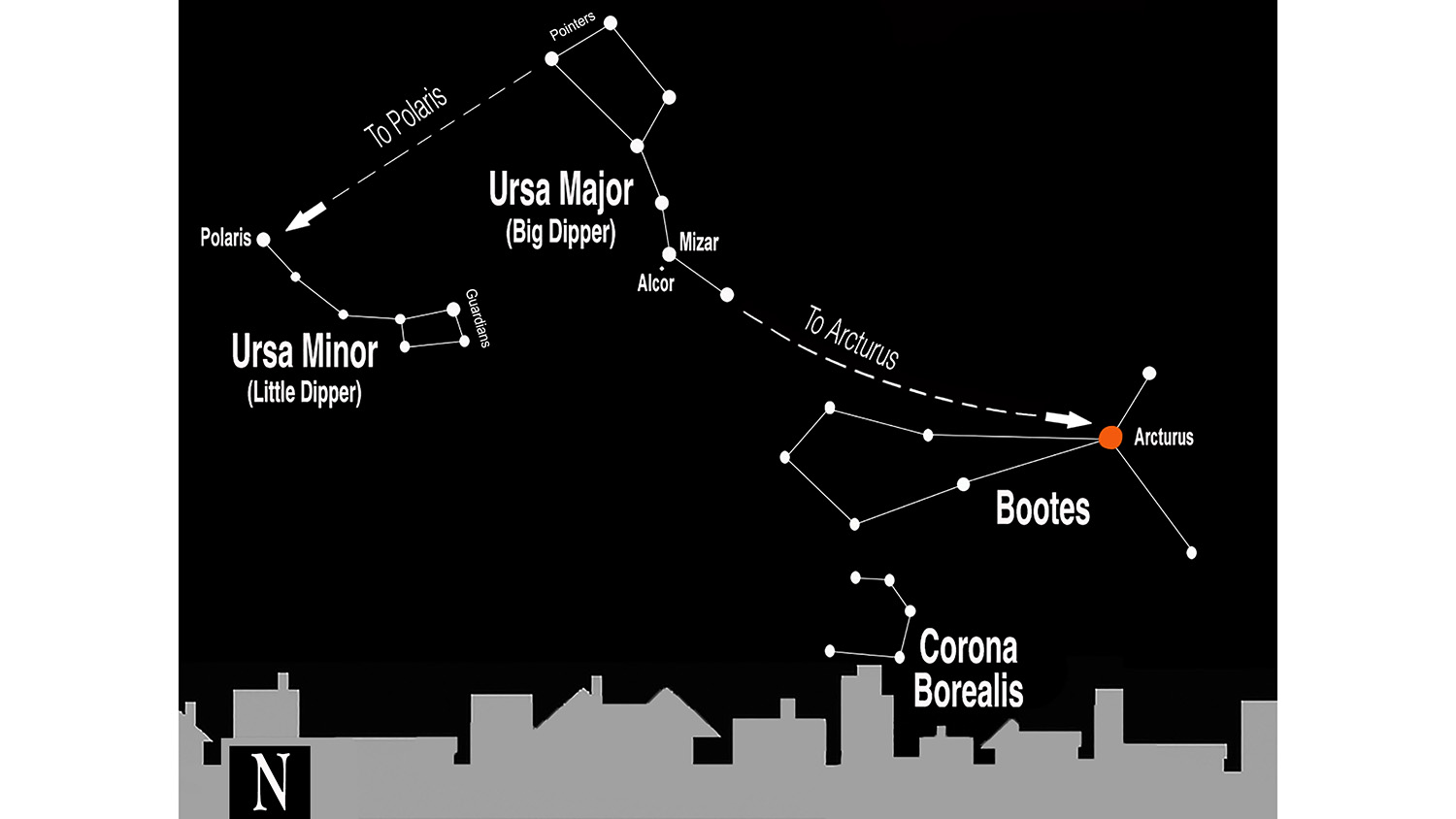

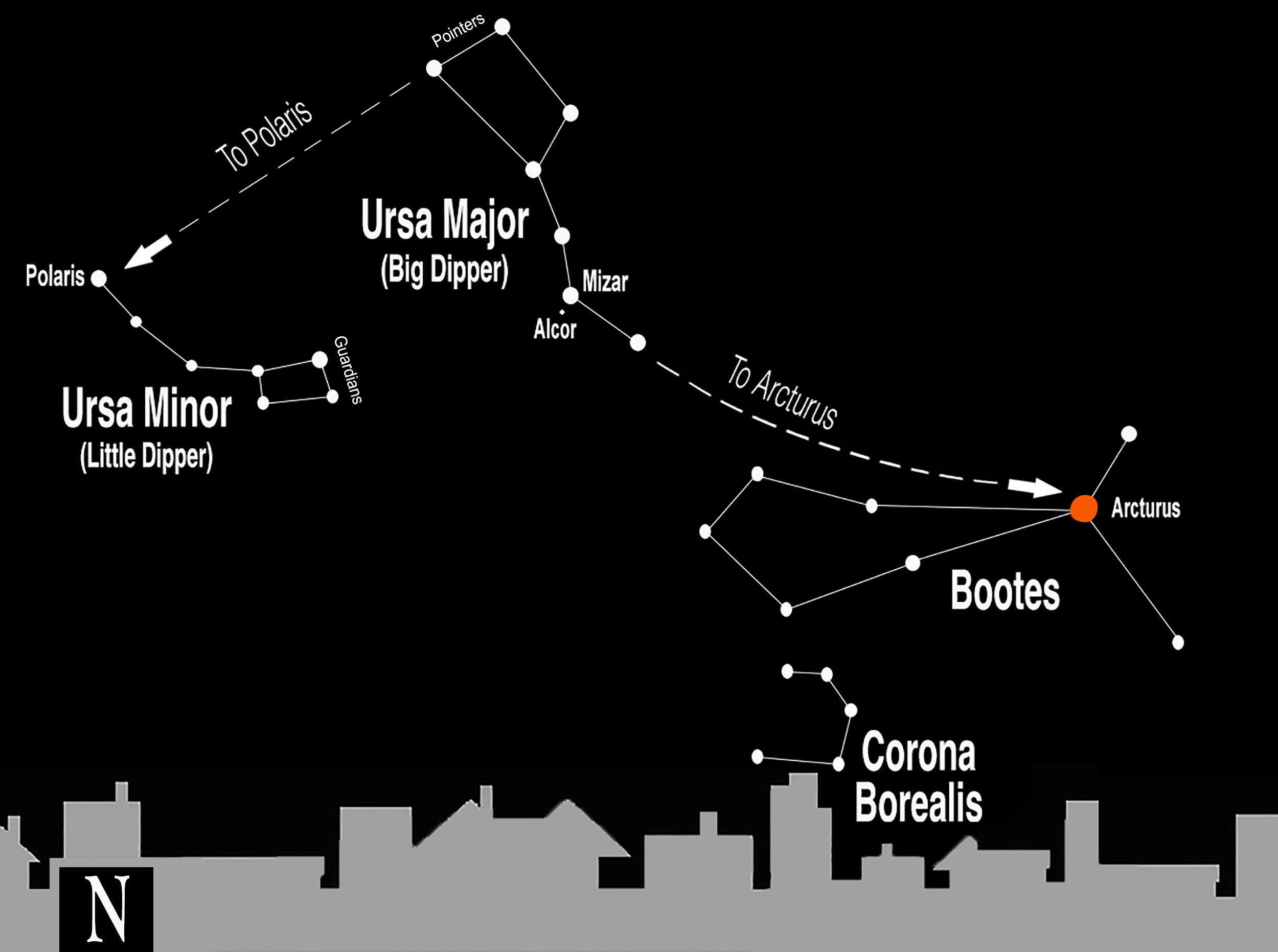

- The stars of the northeastern night sky, as seen in the hours after sunset this week. (The Ironton Tribune | Heath Harrison)

The stars of the northeastern night sky, as seen in the hours after sunset this week. (The Ironton Tribune | Heath Harrison)

Like most people, my great uncle, James Harrison, had seen the Big Dipper many times, especially in the summers, when he spent many a night sitting on a bench, entertaining company in the yard at his Jackson County, West Virginia home.

Deep in the woods on Harrison Ridge, the longtime bluegrass musician lived a good mile or so away from his nearest neighbor on the dirt road and the remote location had some of the blackest skies, free of light pollution, of any area in the state.

But one day, in summer 1986, he saw something different about them.

He and my dad got to talking and noticed that one of the stars in the handle of the Dipper had a tiny companion beside it.

Being a nerdish kid, I had brought along a telescope on our visit, one of many we made pretty much every Saturday that summer.

When looking through the telescope, the pair of stars was easily separated.

“They look like they’re an eighth of an inch apart,” James said, looking back to the naked-eye view of the two stars.

What caught their attention is what is colloquially known as the “horse and rider” star, located in the middle of the Big Dipper.

The duo is made up of Mizar, the brighter of the two, which rotates with its fainter companion, Alcor. The binary star is one of the few in the night sky that can be separated with the naked eye, if you know where to look and have the right lighting conditions.

James’ home, on land that had been in our family since the 1800s, was the perfect place for a young skywatcher to become acquainted with the constellations, and I spent countless hours there on summer Saturdays, taking them in, along with a clear view of the Milky Way, free of city lights. This was while Dad and James sat on the bench, drinking gallons of coffee and trading family stories about oddball relatives from well before my time, whom I heard so many colorful tales about that I feel I knew them myself.

A dark location is ideal for skywatching, but, as the things focused on in these columns show, there are still plenty of features in the night sky than can be seen from most backyards, with no special viewing equipment required.

The constellations of spring in the southern sky are comprised of faint stars, with the exception of a few. But it is during this time that the stars in the northern half of our sky take more prominence.

Most noticeable among these is the Big Dipper, which, contrary to popular belief, is not an actual constellation, but as asterism, an informal grouping of stars.

The seven stars of the Big Dipper are part of the larger constellation of Ursa Major, the great bear, They are all of the second magnitude, the next to the top in the rank of brilliance, and are easily seen in most skies.

It is at this time of the year that the grouping, one of the most well-known in the night sky, begins to reach its highest position.

Beginning around sunset, the Big Dipper begins its climb into the sky, where it eventually appears upside down at its zenith.

The Big Dipper famously can be used for finding direction. By drawing a line from the “Pointers,” the two stars at the furthest end of its bowl, one will hit second magnitude Polaris, the North Star, one of the most significant of the sky.

Only one degree off from the celestial north pole, Polaris remains fixed in its position in the north at all times of the year, while other stars appear to circle around it with the earth’s rotation.

Polaris marks the end of the handle of the Little Dipper, the informal name for the constellation of Ursa Minor, the small bear. Not as bright as the Big Dipper, its fainter stars can often be blotted out by haze and city lights, with only Polaris and the two brightest stars at the front of its bowl, the “Guardians,” visible.

Both Ursa Major and Ursa Minor are circumpolar constellations, comprised of stars close enough to Polaris that they never set year-round in the northern hemisphere. (The southern hemisphere has its own set of circumpolar constellations, not visible to our half of the globe, just as our northernmost stars can’t be seen from Australia or South America).

Just as the Big Dipper can direct observers to Polaris, it can also be used to guide them to another significant star.

By following the arc of the dipper’s handle, one will eventually hit first magnitude, orange-red Arcturus, in the constellation of Bootes, the herdsman.

The third brightest star in the night sky, Arcturus appears even more so, due to the lack of brighter stars (or planets) around it as competition.

The brightest star of the northern celestial hemisphere, it is a red giant, near the end of its lifespan and its light takes 36.7 years to reach Earth (though this is relatively close, as far as stars go).

This colorful star is synonymous with warm weather and first begins to rise in the early weeks of spring, eventually reaching almost overhead and will appear in the primetime hours of the night until early fall.

So in these seasons, take the time to take in the sky sights and enjoy the outdoors, whether from the backyard or in the woods. These can provide memories that can stay with you as long as the cherished ones I have from James’ home from nearly four decades ago, about the time when that light from Arcturus began its journey.

Heath Harrison is The Ironton Tribune’s community editor.