Local man manning Hollywood picket line

Published 12:00 am Wednesday, May 17, 2023

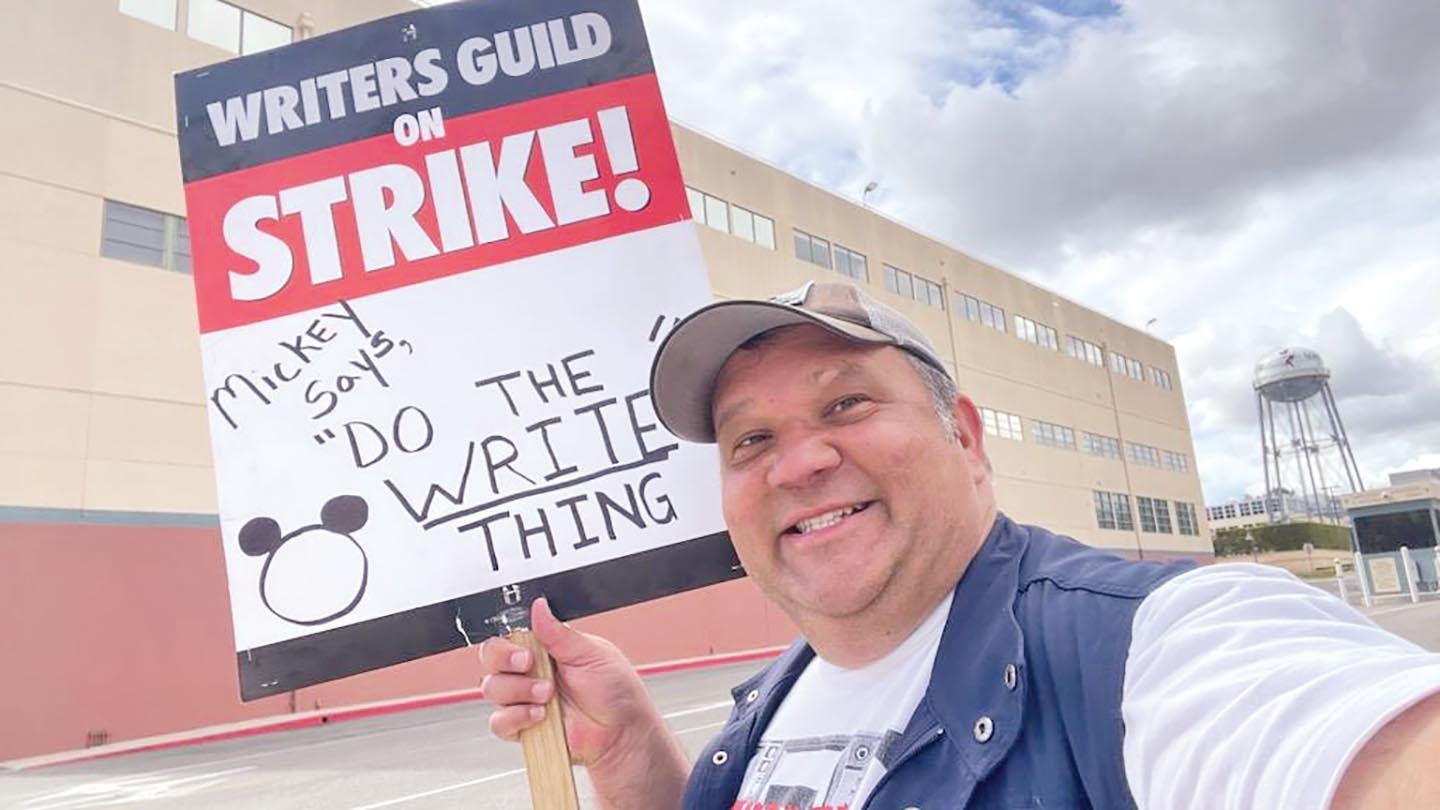

- Mickey Fisher, a Hollywood writer and producer, pickets in Los Angeles, California. He has been part of the Writers Guild of America since 2013 when the show he wrote and created, Extant, was sold to CBS. (Photos submitted)

Mickey Fisher, a Hollywood writer and producer, pickets in Los Angeles, California. He has been part of the Writers Guild of America since 2013 when the show he wrote and created, Extant, was sold to CBS. (Photos Sumbitted)

Mickey Fisher, of Ironton, is part of Writers Guild of America’s strike

While Hollywood is a long way from Lawrence County, but one local man is on strike with the rest of his union.

Mickey Fisher, of Ironton, has been a member of the Writers Guild of America since 2013 when the show he wrote and created, Extant, was sold. The sci-fi thriller ran 2014-2015 on CBS, starred Academy Award-winner Halle Berry, and was a creation of Fisher’s. He co-produced the show with his idol and owner of Amblin Entertainment, Steven Spielberg.

Fisher said the reason that the writers are on strike is complex because they, like everyone, are trying to make a living and that the change in how TV entertainment is being delivered to audiences has drastically changed how they get paid.

And there is talk of artificial intelligence programs that could be used to replace writers.

“What all those things fall under is compensation,” Fisher said. “Because of the past 10 years since I broke into the business with Extant, the entire business has changed with the arrival of streaming services.”

He said when most of the television viewers watched shows on the major TV networks, shows required a lot of writers to create 22 episodes for a season. And if a show became successful enough, it could run for several years. That meant a writer on the show was confident that they could make a good living.

“Think back to watching ‘Must See TV’ on NBC and it was Seinfeld, Friends and ER. Those shows would typically run for 22 episodes in a year. The way the TV networks would make money is they would sell ads and they could price the ads based on the ratings. If they had a hit show, not only would it return, they could make money selling ads,” Fisher said. “It was all very transparent and open.”

Being a writer on a hit show meant a writer was guaranteed to have a contract for 46 weeks of the year, writers’ room would shut down for a month when the show went on hiatus and then they would return to work.

“You had a really steady job, you were able to make a good, middle class income for LA. You could buy a house, you could put your kids through school and there was a certain element of job security,” Fisher said.

He said with the arrival of Netflix, Apple, Amazon and other streaming services, it all changed for writers.

“They have a different model. They create shows to drive subscriptions and they need constant amount of new shows to get subscribers and increase their profits,” Fisher said.

That means they don’t need 22 new episodes every year, they prefer six-10 episodes. And for writers, that means shorter contracts and less writers.

Fisher said he has had jobs that have lasted about six weeks and some gigs that were as short as two weeks.

“So what they have done is turned what was, if you were lucky and broke through, a comfortable middle class profession into a gig economy,” Fisher said. “When your 10-week contract is up, you are back out there scrambling to find another job.”

And the streaming situation means that writers are hired, turn in their scripts and then go off to find another job. In the old system, the writers were around when the scripts were being shot and worked with the actors and producers to do rewrites and ended up getting more job training.

Another big point of contention is residuals. When a show like The Office reached 100 episodes, the network would put it into syndication and other TV channels would run the show and everyone got a cut of the money that generated.

In the streaming model, the shows are only available on the streaming service and aren’t sold to another network. So, the writers and other staff do get a small residual, it is nowhere the same amount of money that shows like The Office, Friends or Seinfeld generates.

“Those residuals were really important when you were trying to survive when you are in between jobs,” Fisher said. “Now, you could be working for a massive hit like Stranger Things, which is a global phenomenon and generates massive profits for Netflix and you are not sharing in that success. So that is another thing we are fighting for. It is just baked into this new model that is unsustainable for writers.”

Fisher said they are not the first writers to go on strike to ensure they are paid and treated fairly and they won’t be the last.

Since Fisher grew up in Ironton, he is familiar with people being on strike, but May 9 was the first time he has ever walked a picket line himself.

“I had no idea how I would feel in the moment, but it was exhilarating,” he said. “I think that it was a huge mistake for the studios to force us out there together because a lot of the writers, since the beginning of the pandemic, we have been isolated from each other.”

He said everyone being together reminded him that it is a vast and diverse community of very smart people.

“And being out there together and walking together is inspiring,” Fisher said. “It has given me a whole new strength and purpose for what this strike is.”