The nadir of American history: Aug. 1814

Published 8:57 am Friday, August 24, 2018

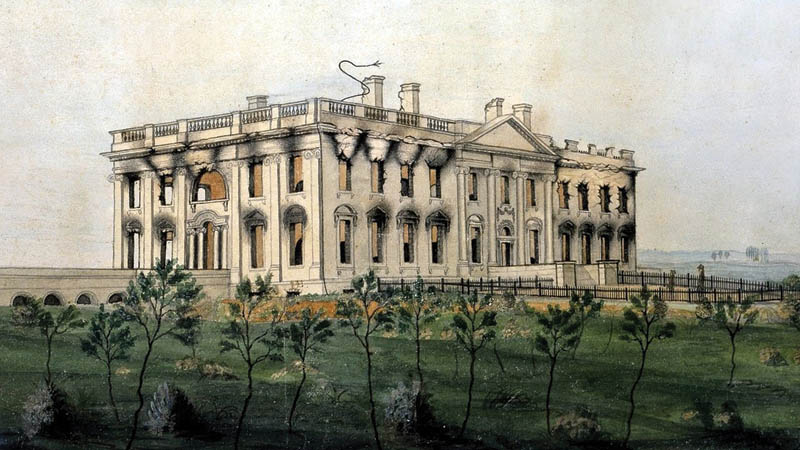

- The charred ruins of the White House are depicted in this watercolor by George Munger, which is on display at the White House today. British troops set fire to the nation’s capital on Aug. 24, 1814, during the war of 1812.

British burned Washington, D.C. during War of 1812

Her husband was pale, thin and small. At five feet, four inches and weighing in around 100 pounds, he was dwarfed by his “handsome” wife, Dolley, in many ways.

President James Madison was very shy and seemed nervous in social situations. He did not like to speak in public, as his weak voice waivered. He always seemed to dress in plain black suits and critics said he “always looked like a man on his way to a funeral.”

Washington Irving described him as a “withered little apple-John.” Some historians have written Madison off as a weak and indecisive president.

“Jemmy” Madison, our fourth president, was, for years, denied credit as perhaps the greatest thinker among all the Founding Fathers. Madison suggested the Annapolis, Maryland, Convention of 1786, which led to the U.S. Constitutional Convention.

In 1787, he authored the “Virginia Plan of Government.” He is known as the “Father of the American Constitution” and the author of the Bill of Rights. This great thinker wrote 29 of 85 essays we now know as the Federalist Papers. Later, he would become Thomas Jefferson’s secretary of state.

His wife Dolley’s goal as first lady was to increase her husband’s popularity and to convince the public that he was a cheerful and friendly person.

She began holding receptions every Wednesday at the “Presidential Palace” or executive mansion. She invited congressmen of both political parties, foreign diplomats, important businessmen, and distinguished Washington visitors.

Although trying to improve her husband’s image, “Queen Dolley” was the star attraction.

Her parties were famous and she seemed to be succeeding in her goal. In fact, she introduced ice cream in Washington, D.C.

However, in the summer of 1812, President Madison brought on sectional controversy when he asked Congress to declare war against Great Britain.

Britain was involved in a European struggle with Napoleon and was seizing American merchant ships and forcing American seamen to serve in the British Navy (a philosophy known as impressment).

In 1814, the British devised a strategy to end the War of 1812 or, as the Federalists called it, “Mr. Madison’s War.” They planned to land a force of regulars and capture Washington. Also, they wanted to attack Baltimore and wipe out that nest of privateers who resided there. Finally, their war office wanted to attack Louisiana by first capturing New Orleans.

In 1813, there were rumors in Washington that British sympathizers wanted to set fire to our capital to avenge the burning of the Canadian Parliament buildings at York (now Toronto) by American soldiers on April 27, 1813.

In the summer of 1814, 21 British warships sailed up Chesapeake Bay toward Washington. Our navy was too small to contest them. On Aug. 19, 1814, the British landed an army of over 4,000 regulars on the shore of the Patuxent River in Maryland and began their march toward Washington.

Major Gen. Robert Ross commanded the British troops and was known as a gentleman of “easy and beautiful manners.” Rear Admiral Sir George Cockburn, who hated the American press, had suggested the American capital as the army’s first object of retaliation.

U.S. Sec. of War John Armstrong was certain that Washington would not be attacked. President Madison put the defense of Washington in the hands of Brigadier Gen. William Winder. The Americans would make their stand against the British at Bladensburg, Maryland, seven miles northeast of Washington.

At one o’clock on Wednesday, Aug. 24, 1814, the British came to Bladensburg. At 10 a.m., it was 98 degrees Fahrenheit. 12 British soldiers had died of sunstroke.

The Americans had dug entrenchments there, but would not use them. An American force of 7,000, mostly untrained militia, was routed by the British. In less than 30 minutes, the Americans ran, in what is known as the “Bladensburg races.”

President Madison had ridden to the battle, but quickly left. He is recognized as the only United States president ever to be with an American army in battle. The path to Washington now lay open.

Washington possessed 900 buildings and was home to 8,000 inhabitants. The residents had procured every stage, cart or wagon, in an attempt to evacuate with their belongings.

Prior to 3 p.m. on Aug. 24, Jim Smith left Bladensburg and rode to the presidential palace to warn Dolley to “clear out…!” Smith was the third messenger to warn Dolley, but she was awaiting her husband.

While waiting, she had gathered articles to be taken away before the British came: state department and cabinet documents, some velvet curtains, a clock, some books, some silver utensils and an embossed copy of the Declaration of Independence.

Dolley gave her pet macaw (a type of parrot) and the key to the executive mansion to the Russian minister.

Madison’s wife angered those with her by wanting to take Gilbert Stuart’s full-length portrait of George Washington from the wall. Difficulty arose. The frame was broken, buy the portrait was retrieved and given to two men from New York.

Earlier that day, Dolley had asked her house steward to prepare a meal for 40 persons, hoping the president and his party would soon return. After many warnings, Dolley, Sukey and Jo Bolin (servants) departed for the safety of Virginia.

The British army arrived on the Capitol building grounds at 6 p.m. on Wednesday, Aug. 24. At the Capitol, Ross and Cockburn ordered Congreve rockets fired upon the roof of the House chamber. The roof failed to ignite, because it was sheet iron.

The British piled mahogany desks, tables, chairs, books and papers and began the burning of the Capitol. At Georgetown College, John McElroy, the college’s bookkeeper recorded the start of the burning at 9:06 p.m.

Next, Cockburn led his men the one-mile toward the president’s residence. The British consumed the presidential meal and the president’s liquor, all the while sneering at little “Jemmy” Madison. Around midnight, Ross and Cockburn set the palace on fire and the interior of the president’s house collapsed within a shell of blackened sandstone walls.

Every government building in the city was set afire, except the patent office. Dr. William Thornton, returning to procure his violin, convinced the British not to burn the former Blodget’s Hotel housing the postal department and the patent bureau.

The British would occupy our national capital for 24 hours. The next day, Aug. 25, a tornado, some say a hurricane, struck Washington and put out any remaining fires. At 9 p.m., the British left Washington. It is estimated they had done $2 million worth of damage.

Returning to Washington, the Madisons heard suggestions to move the capital elsewhere. Congress voted to rebuild the presidential palace, but the Madisons did not get to return. The only American death during the occupation was the grandnephew of George Washington, John Lewis. He was drunk and waved a pistol in a soldier’s face. He was shot at five times.

President Bill Clinton enjoyed taking visitors onto the Truman Balcony of the White House. He showed them a square of sandstone that had not been refurbished and still retained black soot marks.

The blackened walls of 1814 were painted white during the presidency of Madison’s successor, James Monroe.

The president’s home was commonly called “The White House” as early as 1809.

Theodore Roosevelt officially applied the term in 1901.

Bob Leith is retired as a teacher at Ironton High School and a professor at Ohio University Southern and Rio Grande University