History lesson — Aug. 20, 1794: Western ‘Ohio’ open to settlement

Published 7:30 pm Friday, August 23, 2019

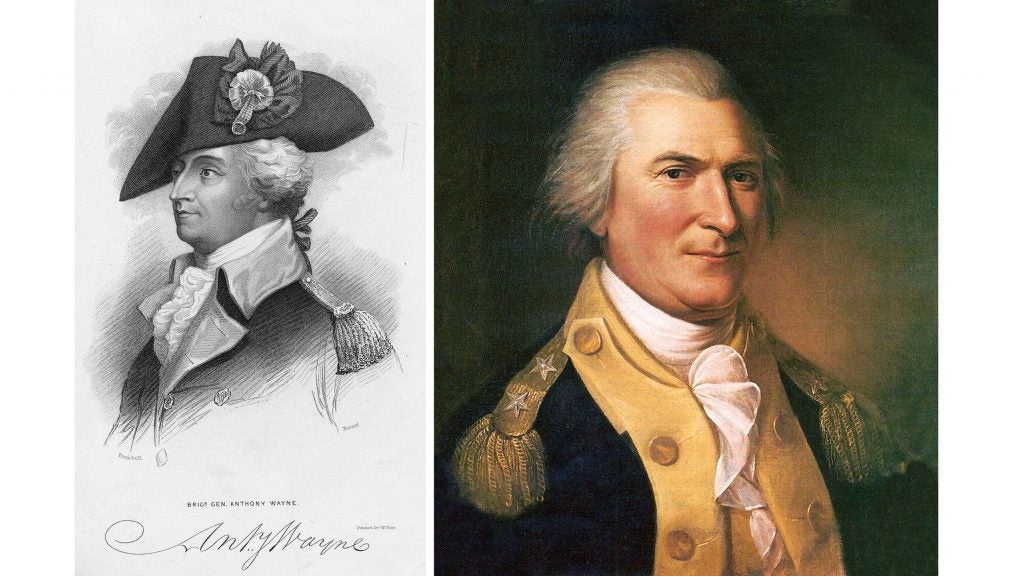

- LEFT: Forces commanded by Gen. “Mad” Anthony Wayne defeated several Native American tribes at the Battle of Fallen Timbers, and the subsequent Treaty of Greenville ended the war, opening what is now Ohio to European settlement. (National Archives) RIGHT: In 1791, Maj. Gen. Arthur St. Clair commanded American forces in what was the United States' worst ever defeat by Native Americans. “(Library of Congress)

The Treaty of Paris concluding the Revolutionary War was signed Sept. 3, 1783. It stated that the American Congress would strongly recommend to its states that they restore rights, homes and properties confiscated from the pro-British Loyalists during the war.

Also, American importers owed British merchants five million pounds sterling. These American debts occurred prior to the Revolutionary War. The treaty stated that British creditors would be allowed to try to collect these debts without hindrances. Progress in these two areas did not satisfy the British, so they refused to leave seven military posts they had promised to evacuate in 1783.

John Jay was sent to England to reduce tensions that might lead to another war. He was told to convince the British to leave the seven Northwest forts. In 1792, the British governor of Canada proposed that the entire territory between the Great Lakes and the Ohio River, together with a strip of New York and Vermont, be made into a satellite Indian state.

The new U.S. government was encouraging settlement of the Northwest Territory. The British in Canada and at these seven forts organized the Indians of the Old Northwest to attack incoming settlers. The British supplied them with food, blankets, muskets, powder and ball and red war paint. President George Washington sought to put down these Indian attacks in the Northwest Territory.

The British were successful in enticing the Iroquois, Chippewa, and Potawatomi tribes to resist white settlement between 1785 and 1787. When the “Ohio” tribes tried to stop westward migration in the Ohio country, the United States found itself involved in an Indian war in the fall of 1789.

Gen. Josiah Harmar, commander of the U.S. Western Army, left Fort Washington (now Cincinnati) in the fall of 1790 with 1,400 men. The Indians heard he was on the march and scattered out into the woods around the Maumee River. Harmar could not find the Indians and turned south in October 1790.

Some of his militiamen “sneaked” back to the Maumee area. The Indians here were well concealed and ambushed these soldiers. The ambush cost Harmar 183 lives and personal military disgrace. The Indians would become even more brazen and more cooperative with the British.

Arthur St. Clair, governor of the whole Northwest Territory, would be named to deal with the Ohio Indians in fall of 1791. His vision was to build a chain of forts in the western part of what is now the state of Ohio, from the Ohio River to Lake Erie at intervals of 25 miles.

He also left Fort Washington with what felt were 3,000 “better trained” and more disciplined troops. On his way to the Maumee River region, he built Fort Hamilton (now Hamilton, Ohio), Fort St. Clair and Fort Jefferson.

His campaign went badly from its beginning. 600 of his troops deserted and he became ill. His army camped out on the Wabash River on Nov. 3, 1791. His remaining army was reduced to 1,400-1,500 men.

They did not bother to establish a defensive perimeter that night. At sunrise on Nov. 4, 1791, the Indians completely surprised St. Clair’s troops. St. Clair left 630 dead and 283 wounded behind.

Nearly 500 of his men escaped unhurt. These survivors ran to Fort Jefferson, 29 miles away. Women and children (camp followers) were massacred and their bodied desecrated.

The news of St. Clair’s defeat reached President Washington as he ate dinner on Dec. 19, 1791. He later screamed out, “Oh, God, oh God, he’s worse than a murderer! How can he answer to his countrymen?”

No American military force had ever suffered such a terrible defeat as that inflicted upon St. Clair’s army on Nov. 4, 1791 on the east fork of the Wabash Rover in western Ohio.

The Indians had killed Maj. Gen. Richard Butler and cut out his heart. Pieces of Butler’s heart were given to those tribes involved in the defeat of St. Clair. The U.S. House of Representatives investigated St. Clair and found him innocent.

A new officer was named to lead the third army to deal with the Ohio Indians. This man was “Mad” Anthony Wayne, a Revolutionary War hero called “Mad” for his reckless courage.

He was “paunchy” and had a gouty leg, but vowed to train his army for frontier warfare. More importantly, he knew Indian customs and the mentality of his enemies.

The Indians knew Wayne and called him “The Tornado,” “The Whirlwind,” “Black Snake” and Chenoten, the “Great Chief.” They called his men She-no-ke-man, the “Long Knives.”

Six miles beyond Fort Jefferson, Wayne’s men built Fort Greenville and wintered there in 1793-94. The British had built a new fort in the area, Fort Miami, on the Maumee River to protect Detroit.

Wayne was counting on his intense dealing before he fought the Indians. He and his men built Fort Recovery on the very site where St. Clair had been defeated.

Wayne spread the false word that he would march against the Indians on Aug. 17, 1794 at any site they chose for battle. Wayne began his march, but made camp 10 miles from the Indians. The Indians always fasted before battle.

Waiting, the Indians grew hungry and angry at Wayne. Some Indians, around 500, went to the British’s Fort Miami for food. Wayne chose this time to attack in what is know as the Battle of Fallen Timbers.

The site of the battle lay between Maumee and Waterville, southwest of Toledo. It would occur on Aug. 20, 1794. The area of the battle was over a mile in length and 640-1,280 feet wide.

The heavy oak timber had been blown down by a severe wind storm (tornado?) a few years before, hence “Fallen Timbers.” Inside the timbers were 1,300 painted warriors with muskets and tomahawks.

Just before dawn on Aug. 20, 1794, a drizzling rain began and the area became gloomy and dark. Wayne’s men progressed two miles in less than an hour. The Indians were beaten and ran to the British-held Fort Miami, but the British would not open the gates.

This epic battle (knives and tomahawks vs. bayonets) lasted between 40 and 60 minutes. Wayne thought about attacking the British fort, but did not. Instead, he built Fort Wayne.

The Battle of Fallen Timbers opened what would be “Ohio” to immigration. The population of the Ohio area had been so small, it had not been counted in the 1790 census. In 1800, Ohio had 45,000 residents. In June 1795, a council of 1,130 prominant Indians was called and on Aug. 3, 1795, the Treaty of Greenville was signed by more than 90 representatives of Ohio’s tribes.

From the Alleghenies to mid-Ohio, frontier warfare was over until Tecumseh led his attacks in 1813. England agreed to evacuate “her” Northwest forts by June 1, 1796.

The United States bought from 12 tribes the rights to the southeastern part of the Northwest Territory, now southern Indiana and eastern and southeastern Ohio, for an outright payment of $20,000 and annual payments of $9,500 in goods.

Next, came the axe and the plow. No longer could a squirrel travel from Lake Erie to the Ohio River without ever touching the ground. The axe of the white man would bring civilization to Ohio’s forests.

Bob Leith is a retied history professor from Ohio University Southern and University of Rio Grande