History Lesson: Thanksgiving —Due to Squanto and Sarah Josepha Hale (Part one)

Published 12:00 am Saturday, November 23, 2019

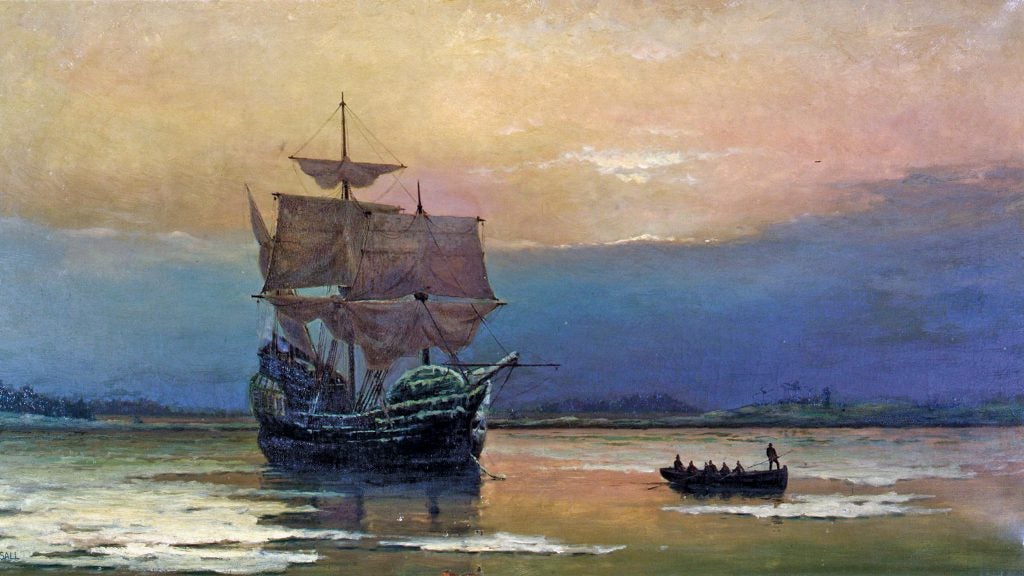

- “Mayflower in Plymouth Harbor,” an 1882 painting by by William Halsall. (Public domain)

This is the first of a two-part series on the history of the Thanksgiving holiday. Look for the second installment on Wednesday.

——-

Arthur Barlow and Philip Amadas, two late 16th century English explorers, returned very favorable reports on new lands along the eastern coast of North America. Queen Elizabeth was so impressed that she suggested the new proposed settlement be called “Virginia,” in honor of herself, the “virgin queen.”

When colonized, the new lands were sponsored and settled for profits for the trading companies supporting the efforts. Little attention was given to desires of the colonists themselves. This Virginia land mass ran from the Great Lakes in the north to Spanish Florida in the south, and from Chesapeake Bay in the east to the Mississippi River in the west.

During the last part of the 1500s and early part of the 17th century, the religious atmosphere of England was rife with dissent in the national church known as the Anglican Church.

Those Englishmen who wished to purify the Anglican Church of all Roman Catholic ceremonies and doctrine called themselves Puritans. They would arrive in North America in 1630 and colonize Massachusetts Bay.

Another group also wanted to purify the Anglican doctrine, but rejected the idea of a state church and wanted to break away from the Anglican Church. Members of the latter group were called Separatists, Independents or Brownists. The English government would inflict a moderate degree of persecution on those people.

The most famous group of Separatists was the Scrooby Congregation, which became a separate church by the fall of 1606. In early summer of 1607, the Scrooby dissenters went to Amsterdam, Holland. Here they sought work, a suitable economic environment and religious freedom.

Seeing their friends falling under the influence of other churches, these Separatists looked for a better place to work and worship. They settled in Leyden, Holland in 1609 and remained there until 1620.

The Scrooby Separatists feared that war would break out again between Holland and Spain. They were also homesick, but could not go back to England. They saw their children falling under Dutch influences.

A minority of the Leyden Separatists thought of Virginia. Their leaders would ask the Virginia Company for a grant of land far enough away from Jamestown so that the Separatists could worship God in their own way and spread the Gospel in that remote land.

The English king awarded them a patent to establish a “particular plantation” in Virginia, but they needed financial support. The Plymouth Company, or North Virginia Company, invested 10 pounds a share in every Separatist who left Leyden. William Bradford, one of their great Separatist leaders, called those who went to Virginia “Pilgrims.”

To receive the 10-pound ‘grubstake,’ the Pilgrims agreed to put their produce into a common storehouse for seven years. They were not allowed to have their own house or home lot or to put aside one day of the week for their own sustenance. This financial agreement was completely done away with in 1626, when the Pilgrim settlers bought out the company officials.

Some historians call the Plymouth Pilgrims early communists (in a purely economic sense). The joint stock company wanted the Pilgrims to send it furs, fish, lumber, sassafras and Indian corne [sic]. Should this economic philosophy have succeeded, there would be a division of profits after seven years of production. However, the Pilgrims wanted individual ownership of property.

These Pilgrims left Leyden in a small ship called the Speedwell and came to England. They would meet a larger ship, the Mayflower, and both would sail for Virginia.

Only 35 of the Leyden Separatists came to England. Other passengers came from England and were neither Puritans or Pilgrims. The Speedwell made two attempts to leave England, but leaked very badly. All of the would-be colonists went aboard the Mayflower. The Mayflower left Plymouth, England on Sept. 6, 1620 for Virginia.

The hold of the Mayflower held a mixed lot of people. 35 came from Leyden, 67 from England and Christopher Jones had a crew of 15. It was crowded in the hold. Besides the 102 people, there were dogs, pigs, poultry and goats.

Daily, the people in the hold ate bacon, hardtack, salt beef, herring and cheese — all uncooked! Beer, not water, was their main drink. On Nov. 9, 1620, they arrived off of Cape Cod. One person had died on the voyage and a baby named Oceanus was born. After a 65-day voyage, they turned into Cape Cod Bay.

Most of the party in the hold knew they were geographically outside the legal jurisdiction of England or Virginia. To stymie any threat of rebellion on the part of the 67 “strangers,” the men of the Separatist group met and signed a compact on Nov. 21, 1620, the same day on which the Mayflower anchored in Provincetown harbor.

The Mayflower Compact was an agreement among 41 of the 44 men that they would form a civil government. This document is a landmark on the road to democracy, because it did commit the Pilgrims to a government based upon “consent of the governed.” This was not a constitution!

After this agreement, the leaders set out to find the ideal site for their colony. They sailed along the shore of Cape Cod and, on Dec. 21, 1620, came to a very suitable harbor. They would build their settlement here and call it New Plymouth, at the former Native American village of Pawtuxet, decimated by the plague.

On Dec. 26, 1620, the Mayflower itself arrived at that specific spot. Four of the passengers had died while the ship lay in Cape Cod Bay. 98 were left.

During their first winter, the colonists were reduced to half of their original number because of disease and the cold. They did build a few houses after dragging logs through the snow. The

Mayflower, upon which they lived while building shelters, left for England in April.

— Bob Leith is a retired history professor from Ohio University Southern and The University of Rio Grande