South Point native studying effects of salt on ecosystems

Published 12:00 am Saturday, December 12, 2020

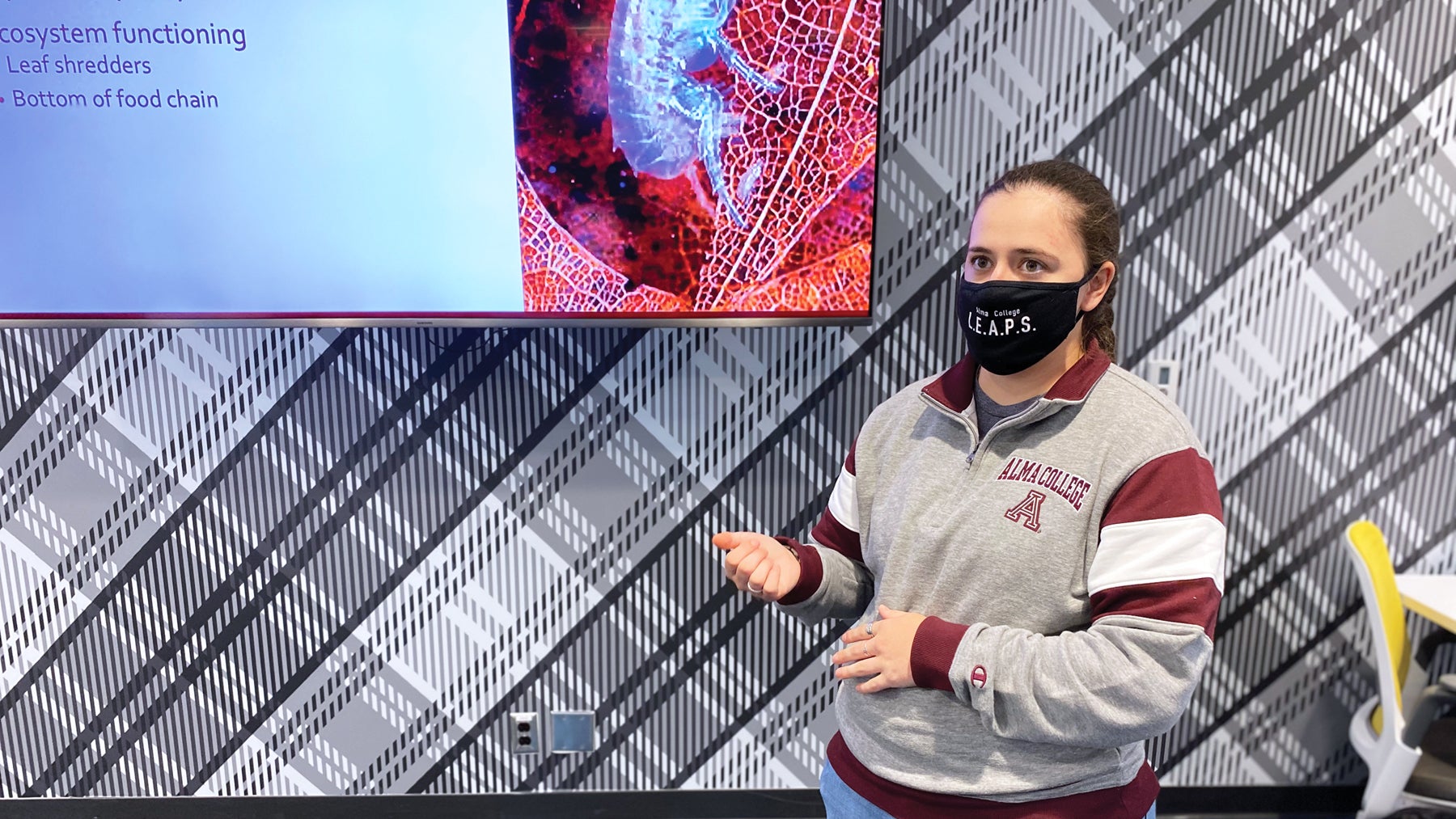

- Camera Stevens, a senior student at Alma College and a 2017 graduate of South Point High School, presented preliminary findings concerning her studies on Hyalella Azteca last month at the virtual Society of Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry (SETAC) North America Conference, an annual gathering of thousands of leaders in government, industry and academia. (Submitted photo)

Camera Stevens, a 2017 graduate of South Point High School, at her signing with Alma College. (The Ironton Tribune | File photo)

ALMA — Every year, billions of pounds of salt are poured onto roadways and sidewalks to make commuting in winter weather a little safer. But student scientists at Alma College say it comes at a cost to the environment, which could have far-reaching implications for animals and people.

Camera Stevens, an Alma senior and South Point native, and Hannah Walker are among several students studying under Amanda Harwood, an assistant professor of biology and environmental studies, to learn more about the effects of road salt on aquatic ecosystems. What the students know, they say, is that the salt doesn’t simply disappear when the snow melts.

“We know that when the snow melts, that salt needs to go somewhere. Where it ends up going, more often than not, is our freshwater systems,” Stevens said. “So, if you think about the plants and animals that live in the freshwater environments of Michigan, and the people who use them for various purposes, and you put lots of saltwater in there, it’s going to have an impact. We’re trying to figure out what that impact is, and what it means for us and future generations.”

At the center of Stevens’s and Walker’s studies are Hyalella azteca, a crustacean commonly found in North American freshwaters. Hyalella are considered an easy species to breed, but apart from that, the students say they are a good invertebrate to study because of their status at the bottom of the food chain.

“They do reproduce quickly, which helps, because we need a lot of them for a study like this. But they’re also an important food source for fish and waterfowl, which is something that is important to a lot of people in Michigan,” said Walker, a junior from Ypsilanti. “Hyalella may not be very large or well known, but if they were to go away, there would be serious consequences.”

Walker explained that she is specifically studying the relationship between reduced food availability and the amount of salt it takes to kill Hyalella. Understanding the interactions between this combination of “stressors,” as Walker put it, could lead to more accurate conclusions about the level of salt we can use on our roads without causing harm to animals — and whether we should switch to a road-clearing alternative, such as beet juice.

Learning about multiple stressors could have even broader applications than road-clearing, Walker said.

“It’s interesting to me to think about how this ability to model changes in system might relate to something as large scale as climate change,” Walker said. “Knowing how multiple stressors can create an impact is important because climate change creates multiple stressors for any organism: higher temperatures, more or less water, new pathogens and other changes to environments.”

Stevens, together with former classmate Isabella Centurione ’20, is studying other factors that could influence the level of toxicity in Hyalella, such as the temperature of the area they live in and the duration of their exposure.

The two presented their preliminary findings last month at the virtual Society of Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry (SETAC) North America Conference, an annual gathering of thousands of leaders in government, industry and academia.

Stevens, who got her start at Alma studying Hyalella as part of the Alma College e-STEM Cooperative Research Experience (CORE) program — designed to give students money to perform scientific research — said undergraduates giving presentations at such large conferences is a rare opportunity.

“To give a presentation and talk about my findings is something I wouldn’t have been able to do without the chances I’ve been given by Alma College and Amanda Harwood,” she said. “I can take this experience and use it in graduate school applications and professional settings.”

Camera Stevens is a 2017 South Point High School graduate and the daughter of Margie Henry and Robert Stevens. She was a South Point Lady Pointers’ soccer standout and signed to play with the Alma College Scots.