HISTORY LESSON: The Town of Gettysburg, A battle and American history’s most famous speech – Nov. 19, 1863

Published 12:00 am Friday, November 19, 2021

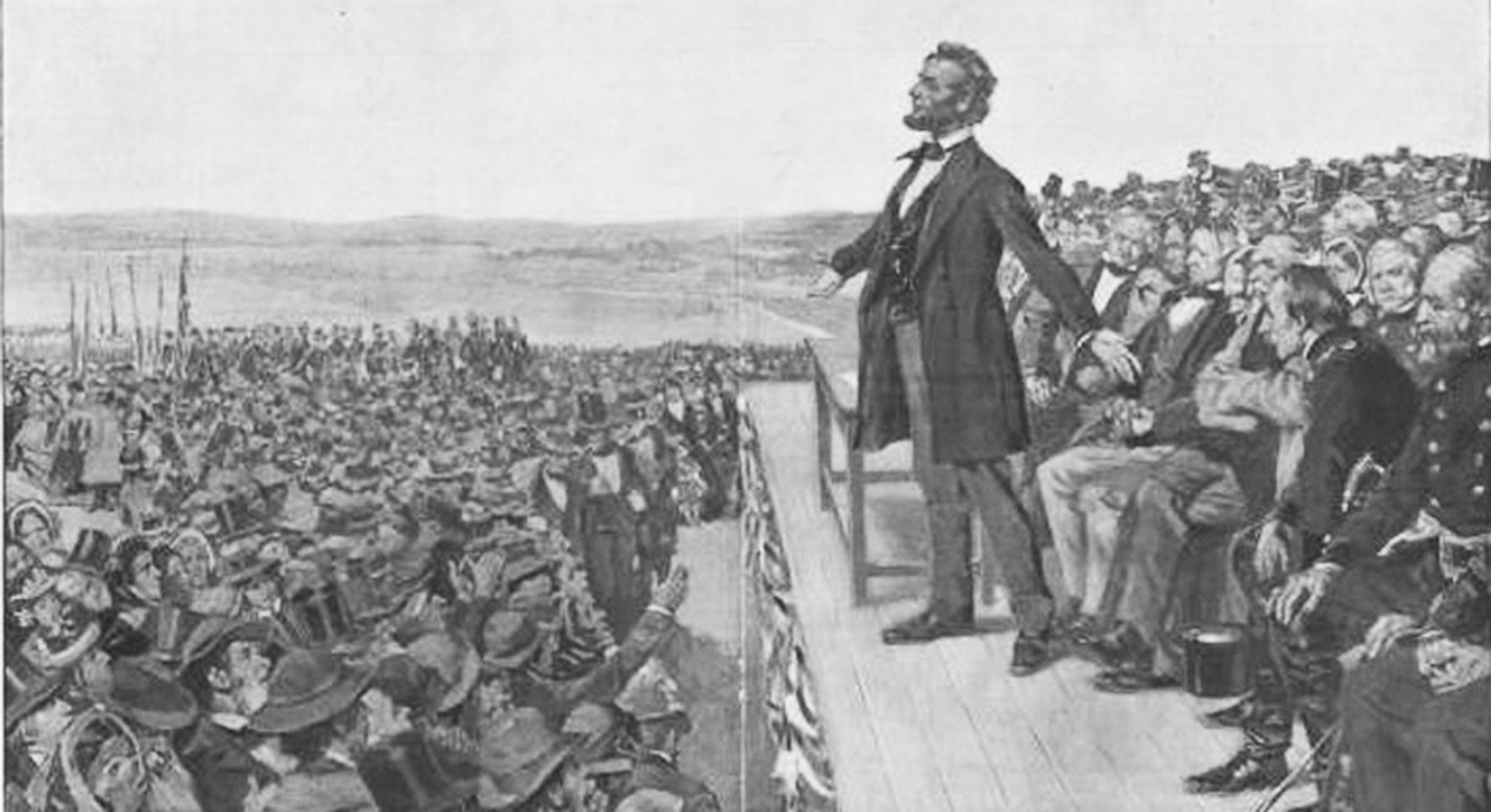

- President Abraham Lincoln delivers the Gettysburg Address on Nov. 19, 1863. Lithograph based on watercolor painting by Joseph Boggs Beale for Harper’s Weekly magazine in 1900. (Public domain)

By BOB LEITH

For The Ironton Tribune

The area around today’s Gettysburg was originally known as the “Marsh Creek Settlement.” In 1785, James Gettys bought 116 acres of his father’s property. On Jan. 10, 1786, Gettys offered surveyed lots for sale and he named the surveyed area “Gettysburg.”

By the time of the Civil War, there were no “Gettys” in Gettysburg. There were 12 roads that led to the town and a tavern became the center of life there. The intersection of the many roads would draw two great armies to fight a battle that would make Gettysburg, in Adams County, Pennsylvania, the best-known small town in all of American history.

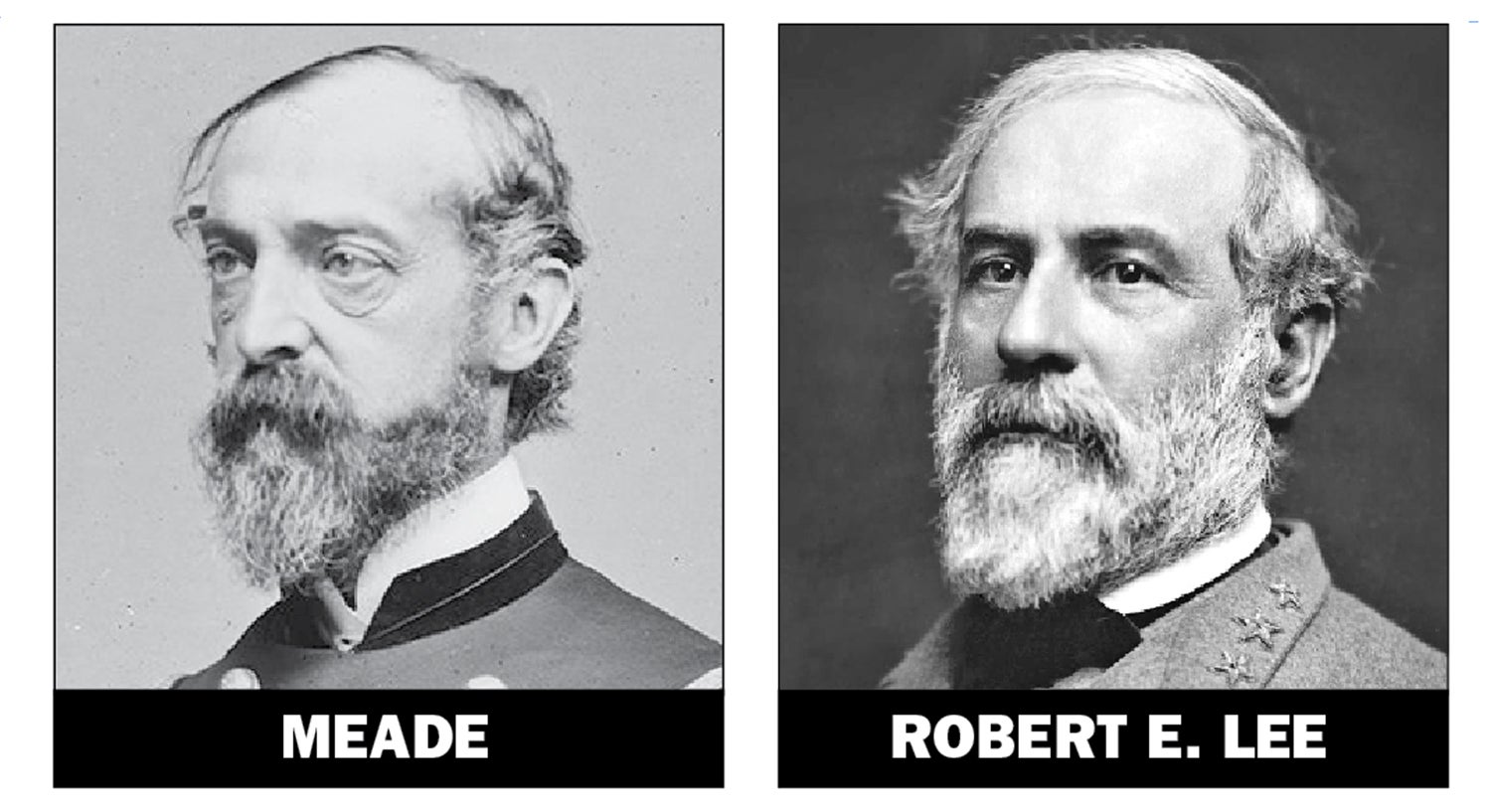

Gettysburg was not important when the Civil War began. Neither Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee, nor Union Gen. George Meade wanted to fight a battle at Gettysburg.

No one knows exactly how many soldiers (those representing the combined armies) converged upon the town of Gettysburg. Lee led the Army of Northern Virginia northward. He is said to have had 72,000 soldiers.

Meade (“The Old Snapping Turtle”) had only been put in charge of the Army of the Potomac three days before the battle. Meade’s army numbered at least 94,000. There may have been as many (both armies combined) as 175,000 soldiers who would fight each other for three days in July 1863 in and around this Pennsylvania town of 2,500. The fate of the United States hung in the balance as the armies fought in the hills, fields and streets of Gettysburg.

Why the invasion of Pennsylvania? Lee, despite the death of Gen. Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson, decided to lead his army to northern soil after the brilliant southern victory at Chancellorsville. Lee wanted to draw the federal army away from the Virginia peninsula and Richmond. Also, he wanted to give the farmers in the Shenandoah Valley a chance to harvest their crops without federal interference.

There were those who felt a southern victory on northern soil might force Lincoln and the United States to peace negotiations. Perhaps European nations might consider official recognition for the Confederacy should Lee win such a battle. Lee hoped to threaten Washington, Baltimore or Philadelphia. Both armies did not know where the other was. Both would summon integral parts of their armies to regroup as one army for a major battle.

Early on the morning of July 1, 1863, a division of Confederates led by Henry Heth, of Lt. Gen. Ambrose P. Hill’s 3rd Corps, headed toward Gettysburg. This division had been in the Gettysburg area on June 30 and had seen Union soldiers. They thought them to be only state militia. (There is a controversial story that Heth was leading his men to Gettysburg to secure much-needed shoes. Such a thought has not been proven one way or another.)

Heth’s men marched along the Chambersburg Pike and ran into Union troops posted west of Gettysburg.

These Union troops were part of Brig. Gen. John Buford’s cavalry force. Buford sought to delay Heth’s march until the 1st Corps of John F. Reynolds could come to support him. Reynolds was 10 miles away.

Two mounted sentinels of the Union army, Kelley and Hall, around 7 a.m. on Wednesday, July 1, reported that they saw the red field of the Rebel flag in the distance.

The two soldiers looked for Sgt. Levi Shafer to whom they were to report. They couldn’t find Shafer and reported instead to Lt. Marcellus E. Jones. Upon reaching the place where the Confederate flag had been sighted, Jones confirmed the march of Heth’s division.

Jones asked Shafer for his carbine. He propped it on the fork of a fence rail and took aim at the Confederate force, a half mile away. Jones aimed at a Confederate on horseback, but didn’t hit him. Lt. Jones fired this carbine at 7:30 a.m. on Wednesday, July 1, 1863, and opened the Battle of Gettysburg, the greatest battle ever fought in the Western Hemisphere.

With the failure of Pickett’s Charge, Jeb Stuart’s flanking attack and Elon Farnsworth’s suicidal charge, all on July 3, the Battle of Gettysburg ended. However, each army, distanced one mile apart, feared another attack the next day, July 4, Independence Day.

Lee decided he must take his army back to Virginia unless Meade attacked him. At noon on Saturday, July 4, it began to rain. By afternoon the rain became torrential, turning the roads into mudholes. Lee prepared a wagon train of his wounded that measured 17 miles in length. However, he had to leave many wounded behind. He took 4,000 Union prisoners with him.

Lee had to wait for the swollen Potomac to recede. On July 13, 1863, 10 days after the battle ended, Lee crossed the river. Some, including Lincoln, were upset with Meade for not attacking Lee’s army while it was building a bridge across the Potomac.

When residents around Gettysburg knew a battle would occur, most men and boys took their livestock and family wealth away from Gettysburg to other towns. The women and girls took food to their cellars to wait out the battle.

Of the 165,000-175,000 who fought at Gettysburg, more than one out of every four lay dead or seriously wounded. There were broken guns and caissons, damaged muskets, cartridge boxes, canteens, torn bloody clothing, knapsacks, dented daguerreotypes, rain-soaked letters and testaments lying in the mud. Even worse were the unburied dead in the hot July sun.

Homes, churches, schools, the Lutheran Seminary, Pennsylvania College’s “Old Dorm,” the county almshouse and courthouse, and almost all farm buildings and barns in the area housed the wounded. In the three day battle, 7,700 had died and Gettysburg sought to care for 20,000 wounded!

Pennsylvania Gov. Andrew Curtin visited the battlefield and was horrified when he saw the half-buried and unburied dead. Theodore Dimon, of New York, felt a national cemetery for all the Union dead should be created at Gettysburg. Dimon convinced David Wills, of Gettysburg, to contact Curtin for his support.

In less than a month, Wills had contacted 18 northern states for their assistance. Wills purchased 17 acres on the western boundary of the Evergreen Cemetery for $2,475.87. A local contractor, Franklin Biesecker, signed a contract for the exhumation, identification and reburial of over 3,300 bodies.

Such work would not be completed until March 1864. Biesecker’s bid for his work was $1.59 per body. No more than 60 bodies could be moved in one working day. More than a fourth, 979, would lie in graves marked “unknown.”

A sad result of the reburials was the collection of 287 packages of personal belongings found on the bodies. Wills had set a date of Oct. 23, 1863 for the grand consecration ritual, which would be attended by huge numbers of people, dignitaries, and perhaps President Abraham Lincoln. The date had to be changed to Nov. 19, 1863, because America’s greatest living orator, Edward Everett, could not possibly be ready to give the main address on Oct. 23. In an afterthought, Lincoln was invited.

There are no known photographs of President Lincoln delivering the Gettysburg address. This detail is from one of two confirmed photos of Lincoln that day,, highlighted at center, taken at noon, just before he arrived and three hours before his famous speech. (National Archives photo)

Lincoln’s son, Tad, had a mysterious fever, Mrs. Lincoln had been thrown from her carriage and the president had to plan his speech for the annual year-end message to Congress.

Many thought Lincoln would not attend the ceremony and others thought him incapable of giving a proper speech. The four-car train left Washington around noon and arrived at Gettysburg at sundown, Nov. 18. His speech was not finished.

Lincoln and Seward would tour the battlefield the next morning. A bugle call from Cemetery Hill woke Gettysburg on the morning of Nov. 19, 1863. At 10 a.m., the procession began to form. At first Lincoln displayed good posture upon a horse that was too small. As he rode, he began to slouch and seemed deep in thought.

Along the parade route, children sold cookies, lemonade, minie balls and cannonballs. A crowd of 15,000 would surround the newly-built platform (12’x20’) to hear mainly Everett.

Earlier that day, a 15 year-old boy, George Gitt, had walked from Hanover and crawled underneath the platform to see Lincoln through the floor cracks. Everett spoke first and gave a classical speech that may have lasted about 2 hours and 8 minutes. He spoke 13,000 words.

Abraham Lincoln would utter 10 sentences and 272 words. He had been asked to render “a few appropriate remarks.” Gitt looked directly at LIncoln’s face as he gave his two-minute speech. The crowd’s applause was sparse and Lincoln told his friend Ward Lamon “…that speech won’t scour. It is a flat failure…” Lincoln would write five copies of the address.

Prior to the battle, a wooden sign hung in the community cemetery. It warned that anyone firing a gun in the cemetery would be fined five dollars. A Union engineer collected 37,000 guns after the battle!

Battle of Gettysburg

Date: July 1-3, 1863

Result: Union victory

Union (Army of Potomac) casualties

• 3,155 killed

• 14,529 wounded

• 5,365 missing and

captured.

Total: 23,049.

Confederate (Army of Virginia) casualties

• 3,903 killed

• 18,735 wounded

• 5,425 missing and

captured

Total: 28,063.

Bob Leith is a retired history professor from Ohio University Southern and the University of Rio Grande.