Strange But True: Lone vote broke deadlocked of election of 1824

Published 12:00 am Thursday, January 27, 2022

By Bob Leith

For The Ironton Tribune

Our second national government was called the Articles of Confederation. This government was ratified in 1781. This government, with a short life lasting until 1789, was purposely made weak and ineffective and each of the 13 states retained its sovereignty.

There was no president of the United States under this government. Men began talking about “revising the articles.” The Constitutional Convention met in 1787 to revise the “Articles” and make a stronger union. The “Founding Fathers” decided to submit a new frame of government and do away with the “Articles.”

After many suggestions, arguing and four compromises, the “Founding Fathers” hoped the states would ratify the newly-written U.S. Constitution. The new government, called for in this new constitution, went into effect March 4, 1789.

This government provided for a president and vice-president. Everyone knew George Washington would be the first president. In fact, he received every electoral vote from the Electoral College. No other president has received a unanimous electoral vote. There were no nationally-organized political parties until Washington and John Adams, his vice-president, took office.

Those who supported the new government were called Federalists and those who opposed the new constitution were called Anti-federalists. During Washington’s first term (1789-1793), political parties began to develop.

The leaders of the Federalist Party were Alexander Hamilton and Adams. Washington believed there was no need for political parties. He felt parties would harm the United States. Those around him considered him to be a Federalist, but he claimed no party affiliation.

The Federalists’ attitude toward the common people was summarized by John Jay when he wrote “that those who own the country are most fit persons to participate in the government of it.”

Federalists blatantly stated that they were the party of “the rich, well-born and able.”

The Federalist Party only won the presidency one time. Adams was the only Federalist candidate to become a president. In the election of 1816, the Federalists nominated their last presidential candidate – Rufus King, of New York. After this election, the Federalist Party virtually disappeared.

Thomas Jefferson left Washington’s cabinet and, along with James Madison, co-founded an opposing party to the Federalists. This opposition party was organized in 1793 and called the “Republican” Party out of respect to the Romans. This new party appealed to the small farmers, frontiersmen and small shop keepers – not “the rich, well-born, and able.”

The Federalists, believing only they should govern the country, derisively called the Republicans “Democratic-Republicans,” affixing the Greek “Democratic” to Jefferson’s original name of “Republican.”

Jefferson, Madison and James Monroe successfully won the presidency as Democratic-Republicans. When Andrew Jackson was elected president in 1828, he dropped the word “Republican” and his party was simply called the Democratic Party.

The Democratic Party divided into factions under Jackson, Adams and Henry Clay. The men who drew up the constitution did not forsee the rise of the two-party system, but its beginnings were found in the debate over ratification of the constitution.

The election of 1824 was the second instance where the results of the Electoral College did not produce a president. The two-party system had died and all of the principal candidates claimed to be Republicans.

In this election, state legislatures nominated men from their geographic regions (“favorite son” candidates”. At the outset of this election, 17 candidates were considering running. Actually, there were six serious candidates left. One of the “serious six,” William Lowndes, had been nominated by the South Carolina legislature for president in 1821. He died at sea in 1822 and the field was narrowed to five.

The favorite of the five candidates was William H. Crawford, Monroe’s secretary of the treasury. He had been nominated by the “King Caucus” method. King Caucus was a method where members of the same party met behind closed doors and nominated men for the presidency and formulated policies.

Crawford, who was the official party candidate, was given the wrong medicine and suffered a paralytic stroke in 1823. One would think that a candidate who was half-paralyzed and half-blind would drop out of contention. He stayed in the race, but never did fully recover. With Crawford refusing to withdraw, the other four candidates would realistically seek the presidency.

From the west came two “favorite sons.” From Tennessee came Andrew Jackson, hero of the Battle of New Orleans. He was the common people’s choice. His enemies considered him a hothead and called him a murderer. From Kentucky came Henry Clay, the “Cock of Kentucky.” He was a powerful speaker of the House. His enemies accused him of being a gambler and drunkard. He lost the presidency three times.

The “favorite son” of New England and New York was John Quincy Adams, son of Federalist president John Adams. He was Secretary of State and had a wealth of education and experience.

Lastly, there was John C. Calhoun, the “favorite son” of South Carolina. He was secretary of war from 1817-1825. After seeing Jackson’s popularity, Calhoun consented to be nominated for the vice-presidency, willing to wait his turn. He would serve as vice president from 1825-1832.

The results of the election of 1824 were inconclusive in both the electoral vote and popular vote. Electorally, Jackson had 99, Adams 84, Crawford 41 and Clay 37. In the popular vote, Jackson had 154,000, Adams 109,000, Crawford 47,000 and Clay 47,000.

Not one candidate had an electoral majority. It took 131 electoral votes to become president. The 12th Amendment of the Constitution stated that, without an electoral majority, the top three vote getters’ names would be deliberated upon in the House of Representatives. Henry Clay was eliminated.

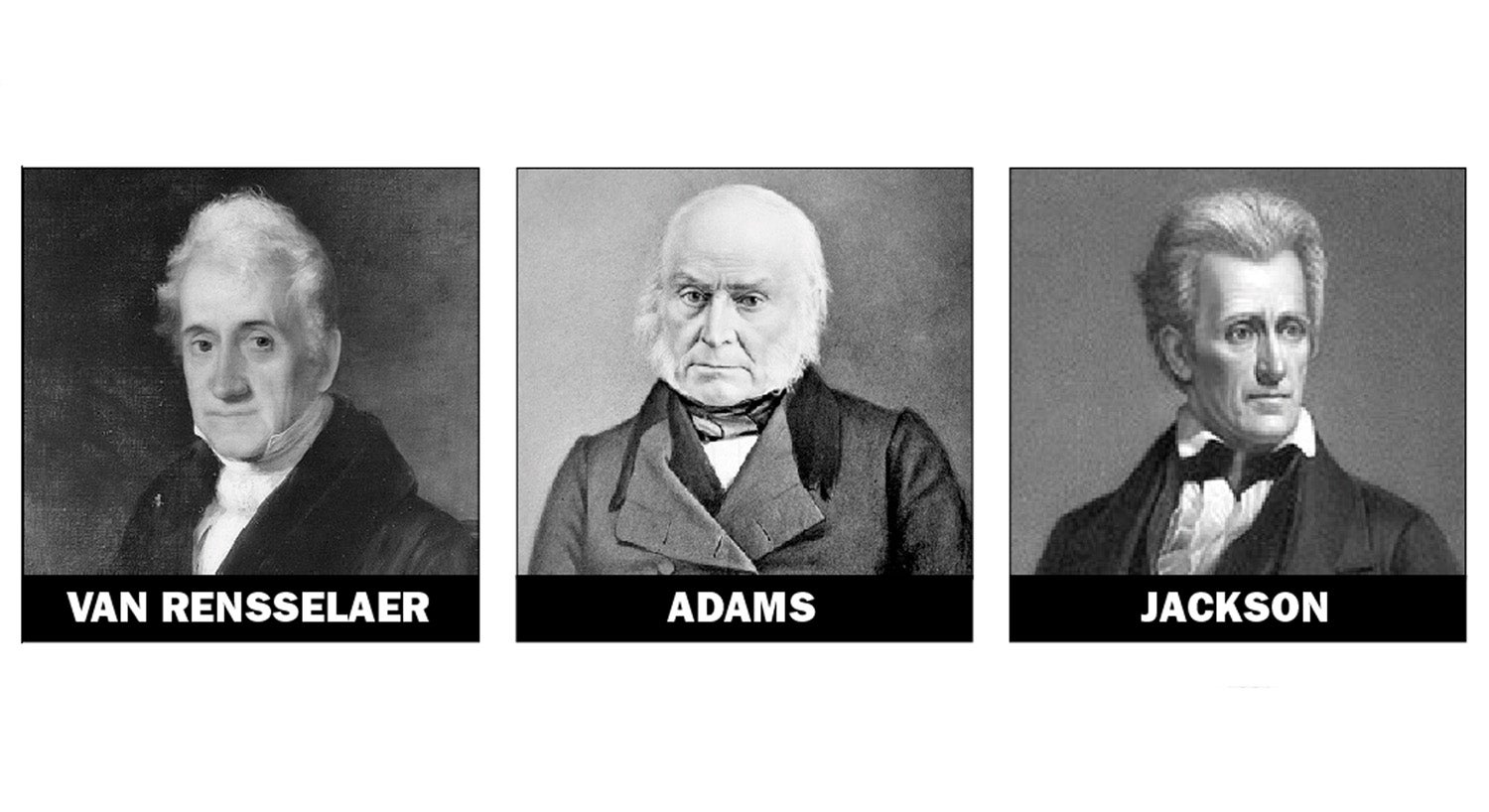

The House vote would occur on Feb 9. Each of the 24 states had one vote to be decided by the majority of the state’s representatives. The candidate who received 13 state votes in the House would be president. Results in the House would be affected heavily by the New York delegation and a man named Stephen Van Rensselaer III. The House of Representatives would elect a president on the first ballot.

Van Rensselaer (1764-1839), of New York, was part of his state’s delegation in the House of Representatives. He owned vast land holdings in New York, was lieutenant governor of New York and major general of the New York militia at the beginning of the War of 1812. He was very wealthy, extremely religious and was a proponent of higher education.

The word spread around Washington that the House delegation from New York was deadlocked 17-17. As a member of the House, he said he would vote for William H. Crawford as he had previously pledged. Speaker of the House Henry Clay felt Rensselaer could be persuaded to change his vote. When the New York delegation arrived on Feb. 9, 1825, Clay and Daniel Webster took Rensselaer into the speaker’s room and used their powers of persuasion.

Clay and Webster failed. Van Rensselaer was very nervous and confused just before the balloting. Before he cast his ballot, Rensselaer bowed his head in prayer and sought divine guidance about his vote. When he opened his eyes, he saw a slip of paper with John Q. Adams’ name on it. This was a discarded ballot. Rensselaer took this scrap of paper to be a “sign from God.” Rensselaer put the scrap of paper in the ballot box, broke the 17-17 tie and made Adams President of the United States.

An ardent Jackson supporter, George Kremer, screamed the term “corrupt bargain,” since Adams named Clay to be his Secretary of State. They had met on a Sunday, but little is known of what happened between them. Adams’ famous diary was totally silent.

This charge of “corrupt bargain” influenced the Tennessee legislature to designate Jackson as its presidential choice in 1828, and so the campaign of 1828 really began in 1825. Calhoun became the Vice-President as he affixed his name to both Jackson and Adams prior to the election of 1824.

The “Founding Fathers” had thought that the Electoral College would fail to elect a president 19 out of every 20 elections. They were in error. Only three times (1800, 1824, 1876) has the Electoral College failed to elect an American president.

Bob Leith is a retired history professor from Ohio University Southern and The University of Rio Grande.