Strange but true: 1800-1875 — Steamboats were Queens of the Mississippi

Published 12:00 am Monday, June 13, 2022

- Steamboats on the Mississippi River in Memphis, Tennessee in 1909. (Library of Congress photo)

By BOB LEITH

For The Ironton Tribune

The Mississippi River is the longest river in the United States. It was formed about 2 million years ago.

Its source is Lake Itasca in northwestern Minnesota and it flows 2,350 miles to the Gulf of Mexico.

This river has been called many things in its history. The Spanish, French, English and many Native American tribes living along it had names for it. It was called Mitchisipi, Missi-sipi, Mis-ipi and Mississippi (the name the French gave it). Regardless of the spelling, these names mean “Big River” or “Great River.”

A token from the collection of Bob Leith from the Southern Belle Saloon of the Mississippi Steamboat, one of the most-traveled vessels, used to pay for “whiskey, tobacco and fancy women.” Leith estimates the token dates to the mid-to-late 1800s. (The Ironton Tribune | Heath Harrison)

The Native Americans had used this river for many, many centuries before white explorers.

After the American Revolution, settlers crossed the Allegheny Mountains and used the rivers as a way to get their produce to market. These settlers could not get their crops to markets in the east because there were not many roads eastward and the ones that did exist were in very poor condition.

Farmers built flat boats from the trees on their land and floated all the way to New Orleans to sell their cargos at a good price. The farmers would sell the flatboat for its lumber.

To get back home, a flatboatman walked or rode horseback over the Natchez Trace. The journey back home could amount to a thousand miles or more. The Natchez Trace was a haven for murderous highwaymen and cutthroats who killed for a traveler’s money.

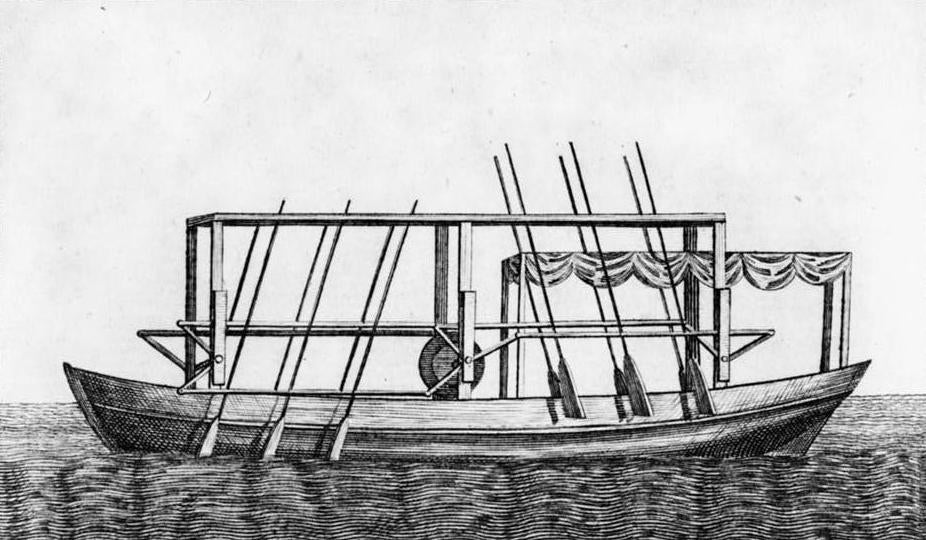

To return home from New Orleans, travelers could take a keelboat up the river. Keelboats could travel upriver as well as downriver.

However, the cost to travel on a keelboat was mostly prohibitive. These riverboats were 60-70 feet long, 15-18 feet in beam and 3-4 feet deep.

Going upriver against the current was very hard work. Where the water was not too deep, the keelboat was poled. Four or five men with long poles took their places on the gangway. At given orders, each man would thrust the end of his pole against the river bottom. The men walked toward the stern and pushed the keelboat ahead.

Where the river was too deep or the current too strong for poling, a towrope, called a cordelle, had to be used. This rope was tied to the keelboat’s mast to help the rope clear the brush on the bank. The cordelle might be 1,000 feet long.

Along the Mississippi with its ever-changing banks, there was no visible towpatch. Men were sent ahead to chop down brush along the bank. Flatboats and keelboats once covered the Mississippi and its tributaries.

There is a saying in European history that “steam is an Englishman.” The use of steampower gave rise to the term “Industrial Revolution” in England around 1760.

This revolution saw a shift of production from hand tools powered by human muscle, wind, water and animals to machines powered by steam. It was only a matter of time until steam would be applied to the steamboat, steam locomotive and steam printing press. Steam would be used in the fields of transportation and communication as well as various industries.

A 1909 replica of Robert Fulton’s Clermont, the world’s first practical steamboat. (Library of Congress photo)

Whereas the British were concentrating on the use of steam in the textile industry and implementing the factory system, American inventors were applying steam to transportation. On Aug. 22, 1787, our “Founding Fathers,” working on compromises to complete our Constitution, gathered at the Delaware River to witness a demonstration of the nation’s first steamboat.

This steamboat was invented by John Fitch. It was propelled by 12 steam-driven paddles (six to a side). Fitch’s steamboat would attain a speed of 8 miles per hour.

Three months later, a Virginian, James Rumsey, launched his steamboat on the Potomac River. Rumsey had worked on this steamboat for two years in secret. America was not ready for steam travel!

Neither Rumsey’s nor Fitch’s steamboats were practical and both men were financially unsuccessful.

In 1807, Robert Fulton, a frustrated artist, took his wood-burning steamboat, called The North River, or Clermont (named after his patron’s New York estate), from New York City to Albany, New York, on the Hudson River.

People called Fulton “The Devil” and they lined the Hudson after wagering where the steamboat would fail along its 150-mile course. Fulton used paddle wheels and completed his journey in 32 hours – 4.6 miles per hour.

His steamboat was inexpensive to build and operate. He invented the first practical commercially-successful steamboat. Steamboats could not be used on the oceans and they damaged canal banks, so they traveled on America’s rivers, mainly the Mississippi, from the early 1800s until replaced by railroads in the latter part of the 1800s.

New Orleans today remains the second busiest port in the United States.

Steamboats competed with each other in size and luxury items. The pilot and captain were the most glamorous persons among the many steamboat travelers. Others were engineers, firemen, roustabouts, stokers, deck hands, cooks, maids, bartenders, barbers, a band to provide music and the gambling element.

However, there were dangers to steamboat travel. Boiler explosions (10 boilers supplied the steam to the two engines if a sidewheelers), fires, river swags and pirates reduced the life of a steamboat to four or five years. River pilots especially hated the rivers’ sawyers.

Hundreds of steamboats moved up and down the western rivers. Tremendous amounts of fuel were used. Cordwood was the fuel of most steamboats, but there was coal available along the Ohio River.

Most riverbank farmers chopped down trees into four-foot lengths. Farmers piled the wood and waited for boats to come in. There were thousands of woodyards along the Mississippi River. The pilot would ring a bell when he needed wood and, if it was very dark or foggy, the farmer would then ignite a bonfire as a guide.

There are many stories about the “Great River” — none so questionable as the account of the Drennan Whyte and its $100,000 treasure in gold. This steamboat blew up and sank in very deep water a few miles above Natchez in the fall of 1850.

In an attempt to salvage the gold, the salvage vessel caught fire and 16 men died. Salvage attempts were given up after a second vessel ran aground.

Twenty years passed (1850-1870). Ancil Fortune and his father had heard the story of the Drennan Whyte many times. While digging a well on land near the riverbank, Ancil’s shovel struck metal. It was the smokestack of a steamboat. Spring floods had displaced the boat.

He filled in the well (questionable land rights) and planted a grove of willows as a landmark. He waited five years for the willows to grow. When digging later, he turned up a brass plate that read Drennan Whyte. He thought he was rich.

Twice the hole filled with water. In the spring of 1881, 11 years after his plate find, Ancil found an iron chest and the gold. He went home to get a sack. He tripped and broke his leg.

That night, it rained in torrents. The river rose and its banks caved in. Ancil dragged himself to the river and died. The river took Ancil and the gold.

The town of Ironton built a steamboat in 1859. It was named The Ironton and it was launched at Washington Street. Many people assembled to watch the 82-foot long boat enter the Ohio. This steamboat was not glamorous or meant to accommodate rich passengers. It was a “working boat” for Ironton’s multiple industries.

Bob Leith is a retired history professor from Ohio University Southern and The University of Rio Grande.