A life of service and honor: Williams remembered for dedication to country, veterans (WITH GALLERY)

Published 5:53 pm Friday, July 1, 2022

As the Independence Day weekend begins, the Tri-State is mourning one of its most storied residents whose heroism and national honors made his life synonymous with service to his country.

Medal of Honor recipient Hershel Woodrow “Woody” Williams, of Ona, West Virginia, died Wednesday at age 98 at the Veterans Administration hospital in Huntington that is named in his honor.

Williams, the last surviving Medal of Honor recipient from World War II, was presented with the honor by President Harry Truman in 1945 for his actions in the Battle of Iwo Jima, where, armed with a flamethrower, the Marine corporal took out a series of enemy pillbox machine gun positions.

U.S. Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin honored Williams on his passing.

“Today, America lost not just a valiant Marine and a Medal of Honor recipient, but an important link to our Nation’s fight against tyranny in the Second World War,” he said in a statement. “I hope every American will pause to reflect on his service and that of an entire generation that sacrificed so much to defend the cause of freedom and democracy.”

Williams was working in Montana as a 17-year-old with the Civilian Conservation Corps, a public relief program of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal, when the Japanese attacked the U.S. Pacific fleet at Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941.

“They called us out on the morning after Pearl Harbor and told us America was going to war,” Williams told The Tribune in a 2020 interview on the 75th anniversary of the war’s end. “And those camps were run by Army people. They said if we were over 18 years old, we could go directly into the Army and be a part of defending America.”

Only 17, Williams had to wait until after he got home to try to enlist in the Marines.

“I simply wanted to be a part of defending America,” he said. “I had never heard of the Japanese. I had no idea where the Pacific Ocean was or anything about Pearl Harbor. My thought was ‘I don’t want anybody to take my country away from me,’ so I’m going to join the Marine Corps to protect my country.”

At 5’6” in height, Williams was at first considered too short for the Marines and it was not until 1943 that a recruiter came to him after the requirement was lowered and asked if he was still interested.

He was recovering in Guam in 1945 from the Battle of Iwo Jima, when he was called to the general’s tent.

President Harry S. Truman presented Hershel “Woody” Williams with the Medal of Honor on Oct. 5, 1945. (White House photo)

“I was real anxious, because you don’t go to the general’s tent unless you’re in trouble, I thought,” Williams said. “And he took me to general’s tent and that’s where I learned I was coming back to the states. If he used term ‘Medal of Honor,’it didn’t register. I was nervous. I hadn’t heard tell of it and I didn’t know such a thing existed.

A few weeks later, he was back in the U.S. and receiving the honor from Truman.

Williams always took his designation seriously, and continued to appear at veterans events throughout the region, well beyond retiring from his job at the Veterans Administration hospital in Huntington.

Lou Pyles, of the Ironton-Lawrence County Memorial Day Parade Committee, said Williams had taken part in both the parade and its accompanying events in the past.

“He came and he always enjoyed it,” she said.

While Scott Evans, president of the Lawrence County Veterans Service Commission, didn’t Williams personally, he said he had an impact on the services that all veterans receive these days.

“Hershel ‘Woody’ Williams was a legend. He was a true American patriot,” he said. “He is a sterling example of American manhood who served his country when called, who spent his life dedicated to helping others and whom we are honored to have a medical center in his name, because it was well deserved.”

Evans said that the advocacy of Williams, and others at the national level through veteran services organizations, “was crucial to getting us the high-quality care that we have available to veterans here locally today. We’ve lost a national treasure.”

In his final years, Williams made his main push to see to it that Gold Star Families were honored for the sacrifices they made in losing a loved one in service to their country.

“Over the years, all the wars we had and casualties suffered, amounting to millions, there has never been anything done in our country to pay tribute and honor families who gave more than anyone else,” he said. “They gave one of their own.”

As the number of World War II veterans dwindled in recent years, Williams, always a fixture at veteran events in the Tri-State, saw his invitations to national events increase, where he served as a representative of his generation of the military.

In 2018, he was invited to flip the coin at the start of Super Bowl LII in Minneapolis, Minnesota, where he was surrounded by other Medal of Honor recipients. And he was invited to the White House in 2020 for the anniversary of the war’s end

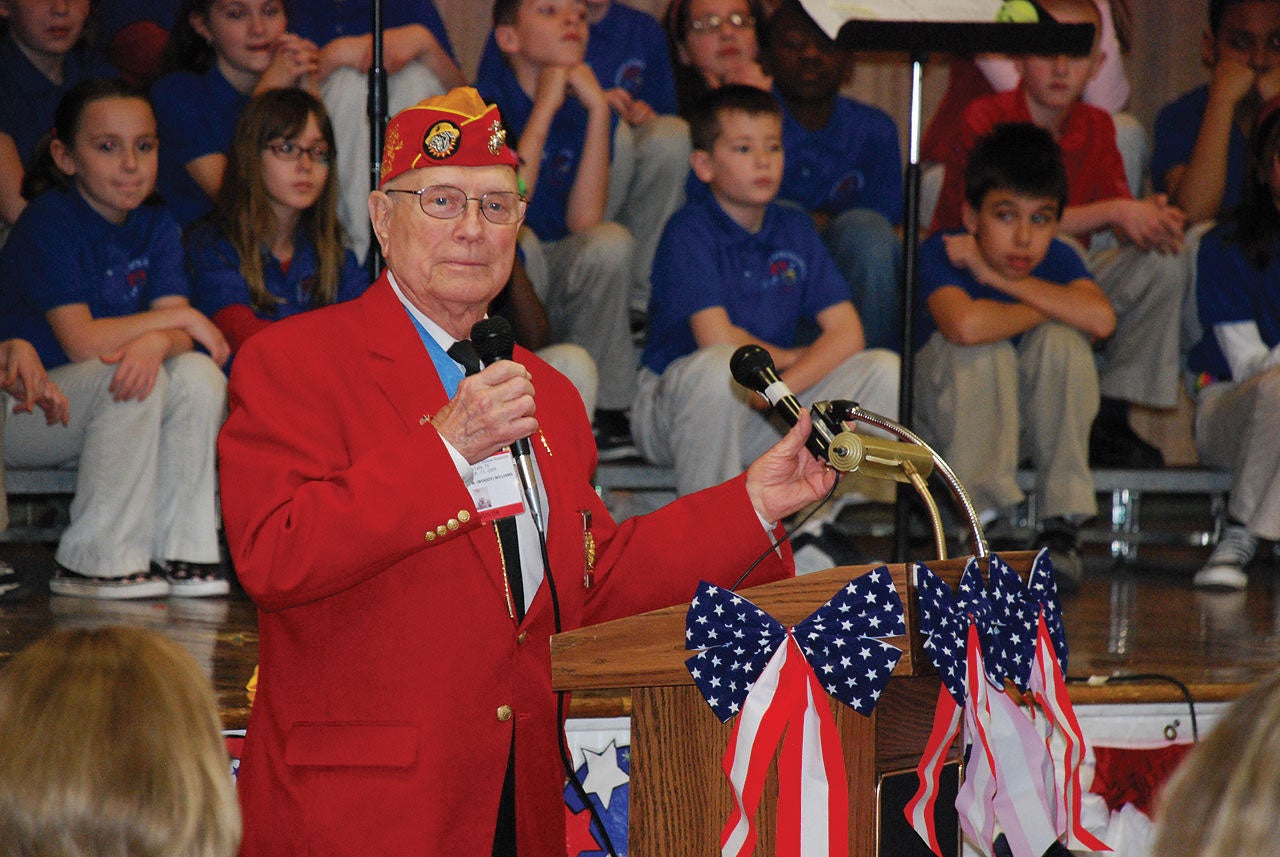

Medal of Honor recipient Hershel “Woody” Williams poses with students and faculty after his presentation at the Tri-State STEM+M School in South Point in 2017. (The Ironton Tribune | Heath Harrison)

However, Williams was still known for taking the time to visit schools locally, where he hoped he could inspire younger generations, as was the case when he visited the STEM+M Early College High School in South Point in November 2017.

Williams shared his philosophy with the students during the visit.

“I believe that circumstances shape our lives,” he said. “All of us are going to be in some circumstances. There was some circumstance that got you here, to this school. The values you have may not have been, had you not been in a certain circumstance.”

“It was put around my neck by President Harry Truman,” he said. “And I was wondering – I’m a farm boy. What am I doing here on the White House lawn, meeting the president, shaking like a leaf?”

Williams told them his life was never the same.

“I then represented something else. I also represented the two Marines who gave their life to save mine,” he said.

In his 2020 interview, Williams explained why he made meeting students a priority.

“If I can influence one or more — the values they have available to them because of the sacrifice of others, they need to have some reverence about that,” he said. “Because they’re possibly living because somebody else sacrificed their life to provide a way they can continue to live in a free country.”

And it was during that year, in which the U.S. was mired in a contentious presidential election and the COVID-19 pandemic had struck that he was dismayed that the division and polarization in the country was “moreso than any time since the Civil War.”

“I know I don’t have a number of years left,” Williams, who was about to turn 97 at the time, said. “But I would like to see something happen in our country that would reunite us as a people. I think, until we do that, were going to continue to have chaos we have in the country today.”

Services for Williams will begin at 8 a.m. Saturday, with a procession leaving from Beard Mortuary in Huntington to the West Virginia State Capitol in Charleston, where visitation will take place in the rotunda 10 a.m.-6 p.m.

Visitation will also take place from 10 a.m.-2 p.m. on Sunday, followed by a service in the Cultural Center in the Capitol Complex. Burial will be private for the family.