ARTS AND CULTURE: Strange, but true: ‘Nothing can ruin him,’ said his friend, Nathaniel Hawthorne

Published 12:00 am Tuesday, July 12, 2022

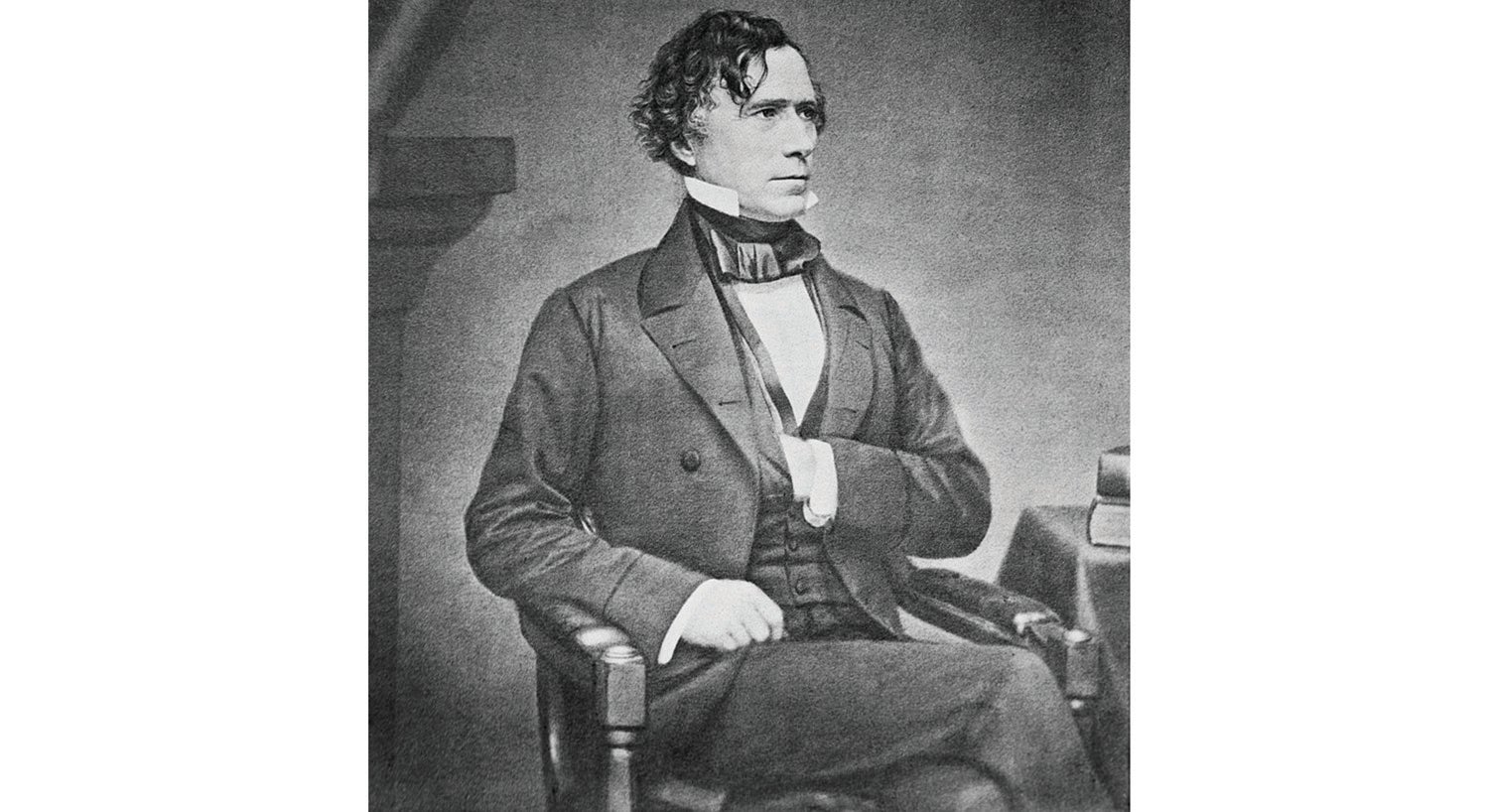

- Frankin Pierce, in a portrait by acclaimed photographer Mathew Brady, taken between 1855-1865. (Library of Congress)

By BOB LEITH

For The Ironton Tribune

The United States has had 11 “great presidents.”

These are those men who filled in the roles as president — William H. Taft and Warren Harding regretted serving their country, as did John Adams, who was defeated by Thomas Jefferson in the “Revolution of 1800.”

From 1849-1861, our nation elected a chain of weak links in the White House — Zachary Taylor, Millard Fillmore, Franklin Pierce and James Buchanan.

Pierce was afflicted with unbelievable bad luck, year after year.

He was born in Hillsboro, New Hampshire, in 1840. His father fought in the Revolutionary War and later served two terms as governor of New Hampshire. His mother was a kindly lady, but was known as a hard- drinking mother.

At age 11, Pierce was sent to an academy in Hancock, New Hampshire. This young boy grew homesick and returned to Hillsboro by walking every mile of the journey. Pierce’s father drove him to a half way point to the Hancock academy and told him to walk the seven miles and get back in school.

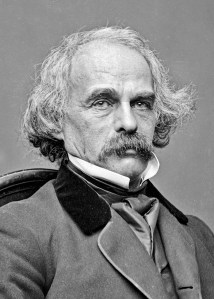

Novelist Nathaniel Hawthorne, seen in this 1860s portrait, was a lifelong friend of Franklin Pierce. (Public domain)

In 1820, he was admitted to Bowdoin College, where he met a lifelong friend, Nathaniel Hawthorne.

Pierce was the first American president born in New Hampshire and the first president born in the 19th century.

In 1827, Pierce opened a law office in Concord, New Hampshire. In politics, Pierce helped secure cotes for Andrew Jackson’s presidential campaign. In 1829, he won a seat in the New Hampshire state legislature.

In 1833, he was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives. At age 33, he became the youngest senator in Washington. Pierce was known as the “Young Hickory of the Granite State.”

On the advice of the older politicians, he did as little as possible and said almost nothing in his years in the House and Senate. His only accomplishment thus far in politics was to help procure pensions for Revolutionary War veterans, known to be bibulous. Pierce was always ready for a rowdy night in Washington.

In 1834, Pierce married Jane Means Appleton, the shy, sickly woman.

From early childhood. she was prohibited from going outside, exercising or being in the sunlight. She suffered from tuberculosis. Mrs. Pierce hated Washington, D.C and often would not accompany Pierce to the city. She hated politics and her husband’s heavy drinking even more.

First lady Jane Pierce, with her last surviving son, Benjamin Pierce, who died in 1853. (Public domain)

The Pierces had three sons. Franklin died three days after birth. Frank Robert Pierce died at age 4. The death of their last son, Benjamin, or Bennie, cast sadness over both mother and father.

At age 9, Bennie was the pride and joy of the Pierces.

Between Pierce’s election to the presidency and his inauguration, the Pierce family took a train from Boston to Concord. Around one mile from Boston, the train crashed on Jan. 6, 1853. The parents were unhurt, but Bennie was crushed to death at the age 11. Neither parent ever got over this loss.

Pierce had been fighting sadness and doubt since 1840 and he decided to never use alcohol again.

In 1846, the United States had gone to war with Mexico. Brig. Gen. Pierce had been put in charge of 2,500 men and he sought glory in the military.

However, bad luck kept coming along. His horse fell upon him and he suffered a leg injury. The next day, he injured his leg again and fainted. When the final drive upon Mexico City occurred, Pierce found himself bedridden with diarrhea.

New Hampshire received him as a war hero, but his commanding officer in The Mexican War, Winfield Scott, called him a coward and Pierce was told to leave the battlefield. Pierce himself knew he had failed in a position of military leadership.

Then came the campaign and election of 1852. Pierce had been retired from politics for more than a decade. The Democratic Party had five men seeking the nomination that year: Lewis Cass, James Buchanan, William Marcy, Sam Houston and Stephen Douglas.

It would take two-thirds of the convention’s members to vote for one candidate to represent the party. None of the contenders could get the necessary votes, so a compromise candidate was needed to head the ticket.

In the presidential campaign of 1852, Pierce was not, at first, even considered. He was almost unknown in national politics, had no enemies, and favored the “Compromise of the 1850” as a final solution to the slavery problem.

On the 49th ballot, he was nominated for the presidency. His opponent in the 1852 election, Scott, his commanding officer in the Mexican War

Scott, the nominee of the dying Whig party, was nominated on the 53rd ballot. It took 102 ballots in 1852 to get the two major candidates!

The Whigs called Pierce military coward, a drunkard and an anti-Catholic. Pierces only qualifications were a handsome face and figure and the fact that he had made no political enemies.

Due to Scott’s hatred of slavery, Pierce won the election of 1852 with 254 electoral votes against Winfield Scott’s 42.

Pierce was the second American president to be called a “dark horse.” This term originated when an unknown or little-known horse won a race over better-known and heavily favored horses.

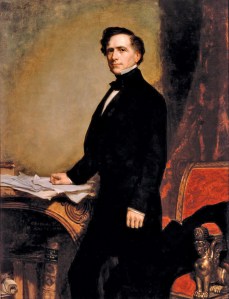

Official White House portrait of President Franklin Pierce, who served from 1853-1857. (White House photo)

James K. Polk was our first “dark horse” president, Pierce was our second and James Garfield, our third.

Two months before his inauguration, the train wreck killed Bennie.

Mrs. Pierce took to her bed and was sure that God had allowed Bennie’s death so that Pierce would have no distractions in his presidential elections.

She felt his presidential election had been bought at the price of her son’s life. Mrs. Pierce did not attend her husband’s inaugurations. She went in an upstairs bedroom for almost half of her husband’s term. She dressed in black every day and wrote Bennie letters.

Behind her back, Jane Pierce was known as the Shadow in the White House. In January of 1855, she participated in a presidential function. When Pierce promised his wife that he would leave politics and just practice law, he encouraged others, behind the scenes, to keep his name “politically alive.”

Also, Mrs. Pierce did not want her husband to take part in the Mexican War.

From the moment of Bennie’s death, the presidency became a nightmare for Pierce.

The New York Tribune states, “We have fallen on great times for little men.”

Further plaguing Pierce was the absence of his vice president, William Rufus De Vance King.

His oath was administered to his in Havana, Cuba, as permitted by a special act of Congress. King died on April 18, 1853 and never performed any of the duties of a vice president and left the burden of facing the nation’s problems to Pierce.

Pierce’s one term as president presented him with many embarrassing incidents.

When a U.S representative was assaulted in Nicaragua, Pierce sent a warship there. The ship’s captain bombarded and leveled Greytown without authority.

To keep a balance of free slave states, there was interest in buying Cuba from Spain. Pierce proposed that three U.S diplomats in Europe pursue getting Cuba.

They met in Ostend and suggested that, if Spain would not sell Cuba to us, we should take it by force from Spain.

Spain refused to sell and Pierce and the United States was very embarrassed. In 1853, Pierce had suggested annexing Mexico and Hawaii and this plan also failed.

One of Pierce’s few accomplishments was to complete a treaty with Japan in 1854, allowing Americans to trade there.

Pierce’s most serious problem concerned the nation’s struggle over the future of slavery. North and South were splitting apart over which new territories would allow slavery and which would not.

Most Americans at the time believed the recent “Compromise of 1850” was the final solution to the festering slavery problem, especially if the federal government enforced The Fugitive Slave Act found in the compromise.

In 1854, Stephen Douglas introduced his Kansas- Nebraska Act, which allowed new western territories to decide for themselves if slavery should spread there.

This choice was called popular sovereignty— let the residents of the territories vote yes or no for slavery at the polls.

Nebraska was too far north to become slave state, but Kansas became a battleground. Pierce endorsed the Kansas-Nebraska Act and stirred up a hornet’s nest.

Those settlers in Kansas against slavery there and advocating free soil were called Jayhawkers. Pro-slavery residents of Missouri wanting Kansas to become a slave state neighbor came into Kansas to use force and violence to vote pro-slavery in Kansas elections. They were called border ruffians.

The land in Kansas was technically owned by helpless Native Americans. Open warfare between Jayhawkers and Border Ruffians occurred between 1854-1860 in a period known as Bleeding Kansas.

Pierce did authorize the use of federal troops, but did little to end a conflict that numbered 50 deaths. The violence in Kansas resulted in the formation of a new political party — the Republican Party of today.

Pierce made a halfhearted attempt to get renominated, but the Democrats turned to James Buchanan. In his final message to Congress, Pierce lashed out against Northern abolitionists, proof of his “Doughface” beliefs.

In March 1857, Pierce came home to New Hampshire, after having pushed the Unites States to brink of a civil war. He and his wife spent two years touring Europe in a vain attempt to improve Mrs. Pierce’s health. She died on Dec. 2, 1863. Called a traitor for his Southern sympathies, Pierce became reclusive.

With his wife’s death, Pierce lost his reason to live.

For 20 years, after his promise to his wife, he had not taken a drop of alcohol. He gave into the temptation to drink again.

He said, “After the White House, what is there to do but drink?”

In his lucid moments he criticized president Abraham Lincoln during the Civil War. The “dark horse,” “Doughface,” and the most handsome president up to the year 1857 drank himself into the grave and died on Oct. 8, 1869.

Pierce’s name was part of a democratic slogan used to persuade voters to vote for him in the election of 1852: “We Polked You in 1844 and will Pierce you in 1852.”

In reality, Pierce is the president no one knows.

His failures as a president may be traced to not recognizing his limitations, a failure to take advantage of his shortcomings and an unbelievable repetition of bad luck.

— Bob Leith is a retired history professor from Ohio University Southern and The University of Rio Grande.