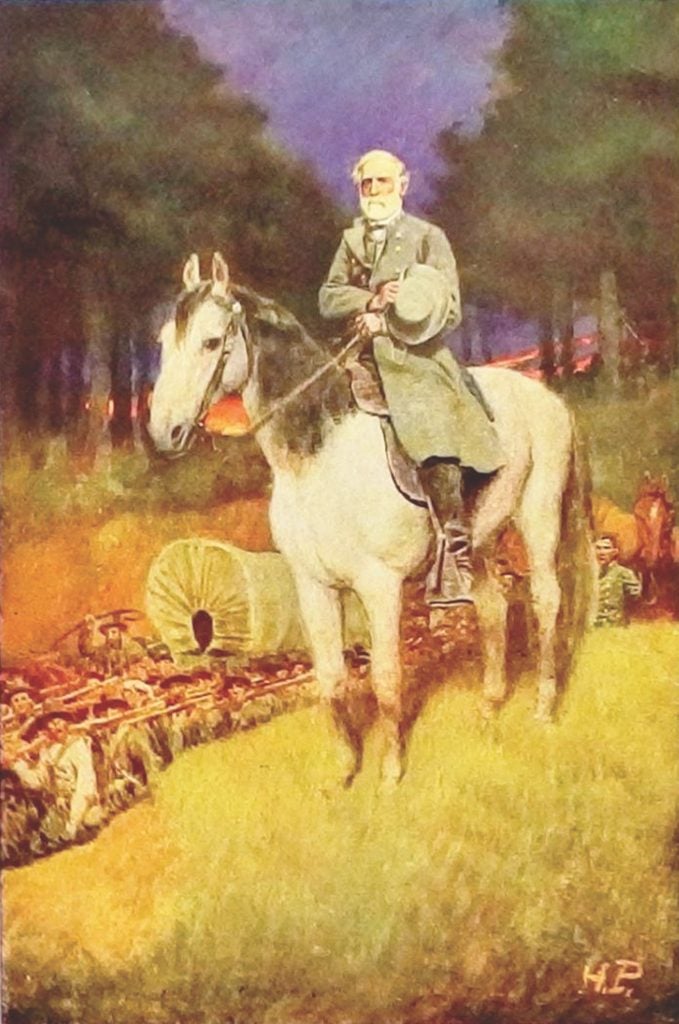

Death of the Marble Man: General Lee died on this date in 1870

Published 10:20 am Saturday, October 12, 2019

He was against secession, freed his 63 inherited slaves before the war and served in the United States Army over 30 years.

Later, Robert E. Lee, accompanied by his young adjutant, Walter Taylor, Lt. Col. Charles Marshall (Lee’s military secretary) and George Washington Tucker, the person who was to carry the flag of truce, set out to meet with Union Gen. Ulysses S. Grant on the morning of April 9, 1865.

A brief cease-fire occurred. Adjutant Walter Taylor asked to be dismissed, because he did not want to experience the heartbreak of surrender. Marshall and Tucker rode ahead to select a proper meeting place for Lee and Grant.

It was Palm Sunday, and the meeting would occur at Wilmer McLean’s home in the village of Appomattox Court House, a hamlet of 12 residences and 130 people, 95 miles west of Richmond.

McLean had owned a farm near Manassas Junction, Virginia, at the time of the First Battle of Bull Run. A shell crashed through a window in his kitchen of his home, “Yorkshire,” in July 1861, and he vowed to move away from this destructive war. Now, four years later, the American Civil War would end at Appomattox Court House in his parlor!

Lee and Grant met from 1:20-4 p.m. A scion of one of the “First Families of Virginia” would surrender to an Ohio tanner’s son.

Lee was free to go. He shook hands with Grant and bowed to Grant’s 13-member staff. After striking his fist into his other hand three times, Lee called for his beloved horse, “Traveller.” He rode back to the apple orchard he had left four hours ago.

His graycoats cheered his return and said they were ready to follow him to battle. He told his men they would be paroled and could go to their homes after stacking their weapons and turning in their flags.

His men cried, as did Lee, and they tried to touch him and his gray horse as he moved toward his tent. Union officers came to visit him and, at Sunday’s sundown, the 25,000 rations from Grant arrived to feed his starving men.

On this day, the Civil War was costing the United States $4 million a day. The invincible “Army of Northern Virginia” was finished.

Lee rode with Taylor and Marshall northeast into Buckingham County. Lee was headed for his rented home in Richmond. That night, he stopped and camped with Confederate Gen. James Longstreet.

Following the surrender, Lee went to his home on Franklin Street in Richmond to rejoin his family. He had nowhere else to go, since the federal government had confiscated Arlington and buried 16,000 Union soldiers on its lawns. He stated he was looking for a quiet place where he could find shelter and his daily bread, if the United States would allow it.

In 1865, Union authorities indicted Lee for treason. Lee, through pre-war friends, asked Grant for help. Lee’s Appomattox parole stated he would not be bothered by United States authority.

Grant agreed to help Lee and threatened to resign from the army if federal authorities arrested Lee, as they had done Confederate President Jefferson Davis.

Lee wrote Grant and enclosed his application to President Andrew Johnson and asked him to end the indictments against Lee and other Confederate prisoners. Johnson suspended Lee’s prosecution and Lee was never arrested. Lee was not given back his citizenship during his lifetime, however.

After the war, Lee was worshiping at St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in Richmond. A black man came up to receive holy communion. The church congregation, used to strict racial segregation, froze in horror. The tension was broken when Lee walked up to the chancel rail and knelt near the black man. After Lee’s action, the congregation came to the rail also.

During the summer of 1865, Lee moved his family to “Derwent,” a rundown house in the Virginia countryside. Lee needed a job in the worst way.

One of his daughters, Mary, privately and publicly told others her father needed a job. A man who belonged to the Washington College Board of Trustees suggested that the college hire Lee as its president. The board of trustees sent Judge John Brockenbrough to “Derwent” to ask Lee in person. A friend loaned Brockenbrough a suit and he borrowed $50 in greenbacks from a Lexington woman.

This school had its origins in 1749 and was called Liberty Hall Academy until 1796, when George Washington donated $20,000 worth of Virginia State Canal Stock to it. Its name was then changed to Washington College.

The college had suffered badly during the Civil War. Union soldiers used college buildings for offices and barracks. Its faculty had four professors and 40 boys under military age. It had meager income and no president.

Lee’s only association with higher education was when he was superintendent of West Point from 1852 to 1855. Brockenbrough told Lee he would have the use of a house and garden, a plot of land to raise vegetables, a percentage of student tuition fees and a salary of $1,500, which the college did not have then.

Lee thought about the offer for three weeks and accepted the position. In the middle of September 1865, he mounted Traveller and left “Derwent” for the 108-mile journey to Lexington, a small town in the Blue Ridge Mountains. His family would come later.

When Lee rode down Lexington’s Main Street, former members of the Confederate Army saluted him. Women and young boys plucked hair from Traveller’s tail.

One thing that Lee insisted upon was that he not be made to teach, as former presidents had to do. He flatly stated, “Teaching is hard!”

At 9 a.m. on Oct. 2, 1865, Lee was to be installed as president in the physics classroom of South Hall. He had no civilian clothing, so he wore one of his gray military uniforms stripped of military insignias and buttons. He would become a curriculum innovator, fundraiser, recruiter, administrator and friend to all.

To all who knew him, Lee was “General Lee” first and “President Lee” secondly. He suggested the elective system at his college. Under his guidance, 10 new departments, including the first departments of journalism and commerce in the United States, were established. Graduate programs were expanded and photography was introduced.

Word came to Lee that the mother of a student from Kentucky had died. The young man could not go home for her funeral. He asked a friend to tell Lee that he would like to be alone in his room for a few days to remember his mother.

When his grade report came to him, he had no recorded absences. Lee visited all his professors and explained the student’s absences. Many young men from throughout the south wished to attend “General Lee’s School.” Its student body increased.

When Lee signed his oath of allegiance to the United States, he quickly sent it to Washington. He mailed his oath on the same day he officially became president of Washington College.

The document ended up on Secretary of State William Seward’s desk. Seward thought it had been processed and gave Lee’s oath to a friend as a souvenir. The friend put it in a desk drawer.

The document was found 105 years later in 1970, and on July 22, 1975, Congress restored Lee’s American citizenship.

President Gerald Ford signed the bill into law, much to the satisfaction of Robert Lee IV, Lee’s great-grandson.

Lee was asking for his citizenship, right to vote and right to hold office.

At commencement exercises at the college in 1867, a five-year old boy, Carter Jones, eluded his parents and came upon the graduation platform to see Lee, who was sitting in a chair on the platform.

Carter sat down at his feet and fell asleep. Lee was supposed to hand out the diplomas. He handed them out sitting down.

Carter Jones always sat with Lee during chapel services each week at the college.

At 4 p.m. on each day that he wasn’t overly busy, Lee went for a ride on Traveller into the Virginia countryside. Sometimes, he would ride to a baseball field to watch the students play baseball. Since neither team had gloves, the scores were very high.

Riding his horse relieved the stress from Lee’s daily duties. He had suffered heart damage around the time of the Battle of Fredericksburg in December 1862.

Lee attended a meeting at Grace Church and its purpose was to build a new church.

The church’s minister, Dr. William N. Pendleton, had been receiving a deficient salary.

In the cold, unheated church, Lee pledged $55 more to meet the necessary amount.

He came home on that rainy night. When asked to give the supper prayer, Lee could not speak. His son summoned his doctors and they stated Lee suffered from cerebral thrombosis, a throat infection and heart disease.

He died at 9 a.m. on Oct. 12, 1870, and his last words were, “Strike the tent!”

On Oct. 10, 1870, Lexington saw 14 inches of rain in 36 hours. C.M. Koones, the local undertaker, had no coffins. The flood had washed them away. Charles Chittum and Henry Wallace, two young boys, found a coffin.

Since the coffin had water damage, it may have been too short for the 5 foot, 10.5-inch president. Lee may have been buried without his boots.

Lee is buried, along with his family, in the chapel called “The Shrine of the South” on his campus, now called Washington and Lee University.

His famous horse, “Traveller,” originally named Jeff Davis, died of lockjaw in 1871. His bones were reburied in 1962 a short distance from “Uncle Robert.”

Lee, in four years, never got one demerit at West Point. Probably, George Pickett is the only American who would like to give him one!

Bob Leith is a retired history professor from Ohio University Southern