Steel Foundation

Published 12:00 am Sunday, July 24, 2011

Region’s industrial past may pave way for its future

William Myers was 15 when he started at one of the pig iron furnaces that littered the landscape around Ironton. With its deceptively feminine name, Sarah was a blast furnace with four white-hot stoves in operation 24/7. That was in 1914.

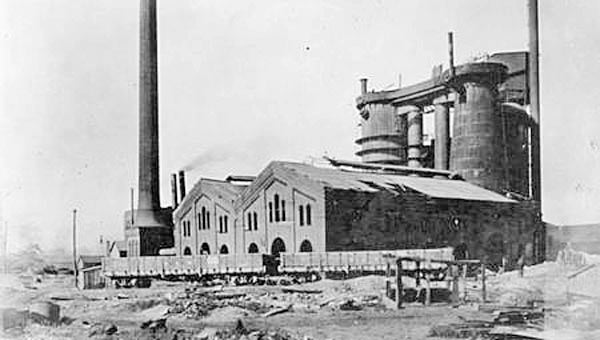

For more than a century the sun over Ironton warred for its place in the sky with the ashy charcoal smoke spewing out of those furnaces. In its heyday in the mid 19th Century there were 45 furnaces belching out heat, filth and prosperity for Lawrence County and its Kentucky neighbors across the Ohio River.

A Bygone Era

Ironton took its place on the national map switching from bucolic farmlands to a destination for wealthy, sophisticated consumers of its goods. In the Deep South cotton may have been the king crop but here cannons and warships were the bread and butter for the ironmasters whose products were the leading props for wars home and abroad.

Myers, who died in 1967, wrote about those days in a reminiscence his stepdaughter, Ruth Hall of Coryville, shared with a local newspaper a decade ago.

“The work was all done by hand and each man worked 12 hours per day,” he wrote. “When they cast, the iron was run in pig beds which were molded in sand. There were three men who molded pig beds. The stock was brought in from under trestles in two-wheeled buggies pulled by men.”

After the iron was poured into the sand molds, four men waited for the metal’s temperature to drop so they could break it into sections. Then that processed iron was carried by hand to horse-drawn trucks where it was loaded into cars and sent over to the Ashland Steel Plant.

That was the operation at the Kelly Nail and Iron Co. where Myers learned how to tend stoves — miserable, grueling work.

“I worked 12 hours per day and highest wages for tending stoves during the war was $5.88 per 12-hour day,” he wrote.

The Fall of an Industry

It took almost 100 years for the pendulum to swing against the pig iron era. The furnaces suffered a slow death as operations went bankrupt from lack of demand or ownership coups or the plants themselves became obsolete.

A family stock fight shut down the Etna Furnace, then owned by the Marting Iron and Steel Co., on the riverbanks by Vine Street. The two-stack furnace that produced foundry and malleable pig iron began operations in 1875 with owners from England.

“It never made money,” according to Richard Marting, a local historian who is distantly related to that branch of the family. “One of the problems was the iron market disappeared after the Civil War.”

In the early 1890s the furnace went bankrupt and was snatched up by a local entrepreneur, Col. H. A. Marting.

“Colonel Marting had a gift for raising businesses from the ashes,” Marting said.

In 1870s the furnace had a value of $100,000, but when it went on the auction block, H.A. Marting paid $2,000 for it.

“Pretty much at scrap value,” Marting said.

The Colonel, who had one child, a daughter, Nellie, put his three nephews in as the management team at Etna.

“It operated successfully until his death in 1919,” Marting said.

However, when the will of the wealthy businessman could not be found, his son-in-law, Dr. Clark Lowry, stepped in.

“Dr. Lowry, speaking for his wife who owned 55 percent of the company, set up a plan that squeezed out the nephews,” Marting said. “When Dr. Lowry squeezed the three nephews, he essentially lost the operating talent of the company. When you combine that with the recession after World War I, it went down and out of business.” But in those economic firestorms that consumed the furnaces came phoenix-like another hard-core industry that became the financial savior for the area. Its name was steel and locally it was known by the acronym that meant jobs — Armco.

The Span of Steel

Just before Christmas in 1921 the Middletown-based American Rolling Mill Co. — Armco — bought a furnace on the main street of Ashland, Ky. in the west end of the city.

Three years later was the start of the first continuous sheet-rolling mill in the Tri-State. By the time the United States was embroiled in another World War, Armco was one of the area’s largest employers.

Richard Marting was a young engineer when he started work at the Ashland mill in 1965. He stayed there for 30 years.

“In 1982 there were 5,000 employees,” he said. “When I left in ‘95 it was 1,200. If you look at it on Google Earth, the whole middle of the place has been ripped out and torn down. It looks like the (Dayton) Malleable site today. When you think of the American steel industry, Bethlehem, Republic, Inland J&L, National, they have either been torn down or gobbled up by someone else.

“When I went to work at Armco in 1965 the Japanese were coming to America to buy technology to take back home. When I left in 1995 Americans were going to Japan to buy technology to bring back here. It was a ski jump. When I went there, it was at the top and when I left it was in the pits.”

Sherry Lee Lindon and John Russo are co-founders of the Center for Working Class Studies at Youngstown State University, and co-authors of “Steeltown USA,” a look at that industry in the northeastern part of the state. Lindon sees the decline of steel on the national stage as a result of multiple factors.

“It is a combination,” Lindon said. “The steel industry companies began to be bought by corporations who were involved in multiple kinds of things. For some of them making steel was not their primary interest.”

That corporate diversification coupled with globalization hit the U.S. market hard.

“Steel companies in Japan, Germany were more able to compete with the U.S.,” she said. “Moving back and forth became easier. It was easier to run a global corporation because communication got better. You could from the U.S. run a factory in another country much more easily. Better telephone technology, readily accessible computer technology, all those things, where maybe you could get cheaper labor.

“Also the United States wanted to do a better job in protecting its water, air and soil in ways other countries weren’t doing. It was a way to get away from regulations. As industrialization grew, it began to make more sense to make steel closer to where you were making a car. It is really a complicated picture. You cannot say there was one specific cause.”

A New Age?

About three years ago county officials watched the rise and fall of the prospect of a proposed steel mill at the border of the Lawrence and Scioto counties when Russian steelmaker Magnitogorsk Iron and Steel Works, or MMK, pulled out.

MMK had planned a $1 billion electric arc mill centered on making and customizing steel for use in the chassis of cars and trucks. Even after the Russians withdrew from the project, development officials still pushed to find another way to construct that mill.

Entrepreneurs willing to build haven’t been found yet but some economic development insiders refuse to say the project is dead.

Last week as Armco Steel, now known as AK Steel, functions as a shell of itself, Lawrence County got a new employer and a new kind of steel company.

Chatham Steel, a Savannah, Ga.-based metals distribution center, opened its sixth company site at The Point industrial park, with 20 employees now and plans to double that figure. However, Chatham is a steel company that’s never produced a roll of metal. Rather it cuts and ships out the pipes, rolled bars, stainless steel and carbon and alloy plate made elsewhere.

Chatham president Bert Tenenbaum jokes it’s like a Sam’s Club.

“Most customers we target will buy three of this and two of something else and they want it tomorrow,” according to Tenenbaum whose grandfather started as a scrap dealer in 1915.

As a third-generation entrepreneur Tenenbaum agrees the U.S. economy is now service-driven, but refuses to sound the knell for manufacturing in this country.

“Service jobs seem to be what are capturing attention,” he said.

But service jobs bring with it a need for steel, whether for offices, hospitals, shopping centers, bridges or highways, he said.

“Manufacturing in this country, while it is not what it was, it is still a major force in economic terms,” he said. “This country is still a leader in manufacturing.”