Bob Leith: Strange, but true – America’s first original folk hero (Part 2)

Published 12:00 am Tuesday, August 16, 2022

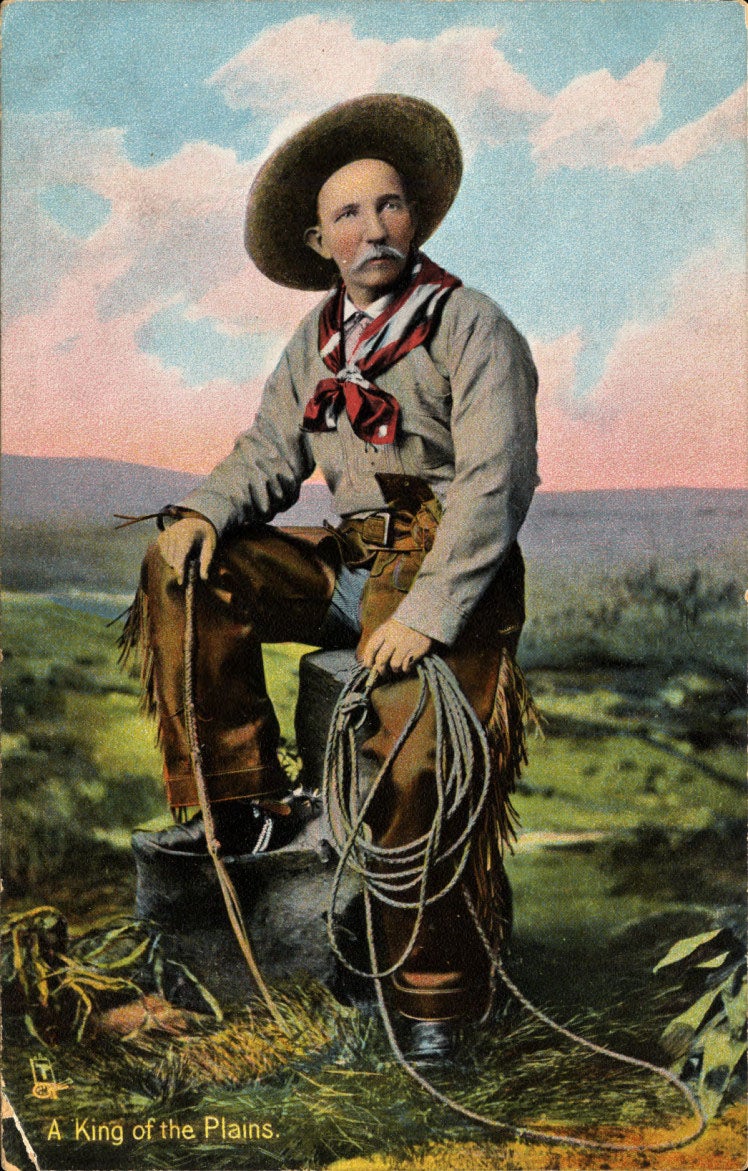

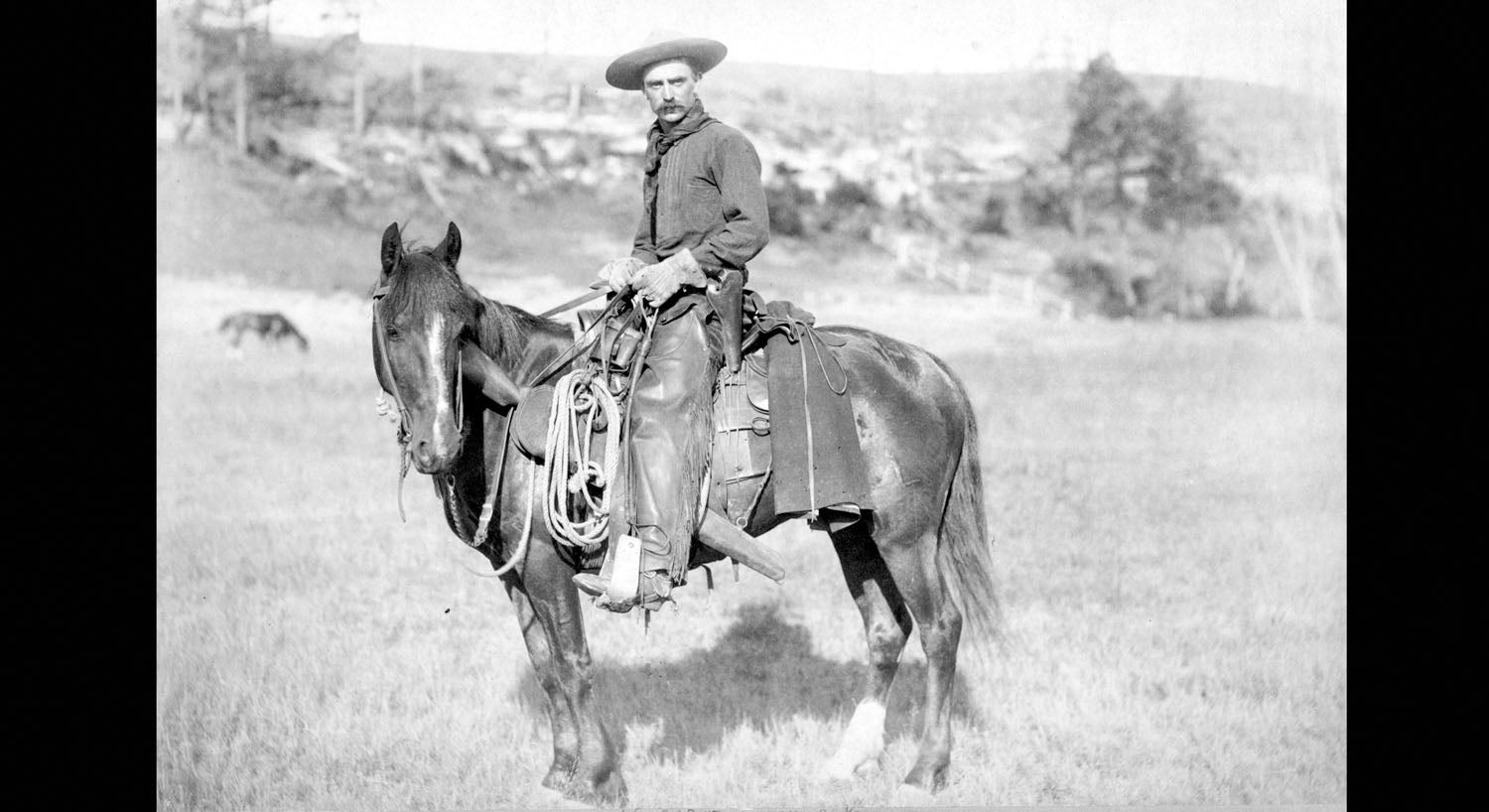

- An American cowboy, circa 1897. Photo by John Grabill (Library of Congress Prints and Photographs division)

By Bob Leith

For The Ironton Tribune

EDITOR’S NOTE – This is the second in a two-part series. The first installment can be found here.

In 1820, Maj. Stephen H. Long explored that area between the Missouri River and the Rocky Mountains.

His assessment of that land reads at thus, “…that land is almost wholly unfit for cultivation and of course uninhabitable by a people depending upon agriculture…”

On the map, Long drew of that area, he called the land in question the “Great American Desert.” The very name Long gave it retarded American settlement there.

Today, we call this area the Great Plains. It also has been called the “Wild West” and the “Last West.” This area was known as the “Great American Desert” until the beginning of the Civil War. Long’s description of the land told of a lack of water and timber there.

These Great Plains extend some 300,000 to 400,000 square miles or 1/10 to 1/8 of the United States. The average yearly rainfall was 15 inches and there was little vegetation other than drought-resistant grass called buffalo grass. This “Last West” was populated by antelopes, jackrabbits, coyotes, wolves, prairie dogs, 12 million buffalo and 200,000-275,000 Plains Indians.

By 1870, there were 6 million white settlers on the Great Plains and, by 1890, this last frontier was declared settled. Cattle ranching would dominate the use of this land from 1865-1885. Conflict would arise among the cowboys, homesteaders, sheep farmers and Indians who felt others were trespassing on their lands.

Throughout the Great Plains, temperatures of 100 degrees Fahrenheit and higher were experienced in summer. In Kansas, it was not uncommon to have 25 consecutive days at 100 degrees or higher. In winter, the northern areas (Montana, Wyoming and South Dakota) were known for blizzards and temperatures may fall to 50 degrees below zero. Temperatures, affected by winds, can drop 50 degrees in one day. Cowboys called the winds “blue northers.”

The “Era of the American Cowboy” lasted a bare generation, from the end of the Civil War (1865) until the mid-1880s when bad weather, poor range management and falling cattle market prices brought an end to the heyday of the cattle industry.

The total number of cowboys on the Great Plains did not exceed 40,000. The average age of the American cowboys was only 24 years. During the “Era of the American Cowboys,” 10 million cows and 1 million horses walked the trails from Texas to railheads in Kansas and Missouri.

Other cattle went to Wyoming and Canada to be sold as brood stock instead of being sold for beef in Eastern food markets. A small herd might number no more than 500 head. The largest herd to go on the long drive was 15,000 in 1869. The ideal size of a Texas herd was 2,500 to 3,000 head. Cowboys desired to drive four-year-old steers on the long drives.

A cowboy’s life centered around four separate phases – life on the ranch he was working for, the roundup and branding, the long drive north and the passing of time from when the herd was sold and when the grass turns green in Texas (April.)

Cowboys lived in a rather crude shelter called the bunkhouse. Prior to the roundup and branding, cowboys were asked to do other work at the ranch that hired them. They might be asked to pitch hay, clear brush, break horses and hunt stray cattle. They might also be asked to chop four feet lengths of wood for the cookstove. Prior to the roundup, cowboys inspected and provided maintenance of their personal equipment.

Horse hooves were trimmed and horseshoes nailed on the horses’ hooves. Wild horses had to be broken for saddling. Men who broke the horses were called “snappers” and these young bronco busters were paid so much per broken horse. Chuckwagons were overhauled, axles greased and a supply list was made out. The “cooney” was a cowhide sling underneath the chuckwagon. It held firewood and dried buffalo manure called “buffalo chips.” It had to be properly affixed between the wagon wheels.

The cowboy had to check his personal equipment because he would be away from civilization three or four months. He gathered his bandanas. He made sure his chaps were in good order.

He had new heels put on his boots to keep his feet from going through the stirrups. Repairs were performed upon his 40-pound saddle and bridle. His lariat (18 feet in length) was tested for roping steers. His hobbies were inspected so that his night horses would not get nervous and run. A cowboy’s bedroll consisted of a 7×16 foot tarpaulin and soogans, square-shaped quilts, and a double blanket sheet. His pillow was his saddle.

The cowboy’s bed was likely to contain tobacco sacks, shaving needs, cigarette paper, pieces of leather, possibly a picture of his girlfriend, old letters, worn out magazines, an extra pair of boots, dirty clothes, an extra bellyband, his rope and a raincoat. When the cowboy’s bedroll was rolled and tied, it might weigh 150 pounds. It was placed in the floor of the chuckwagon during the day. After 15-18 hours in the saddle, his bed on the soft grass felt good. Cowboys only had two pleasures once the long drive began – the campfire where coffee was always kept hot and his bed.

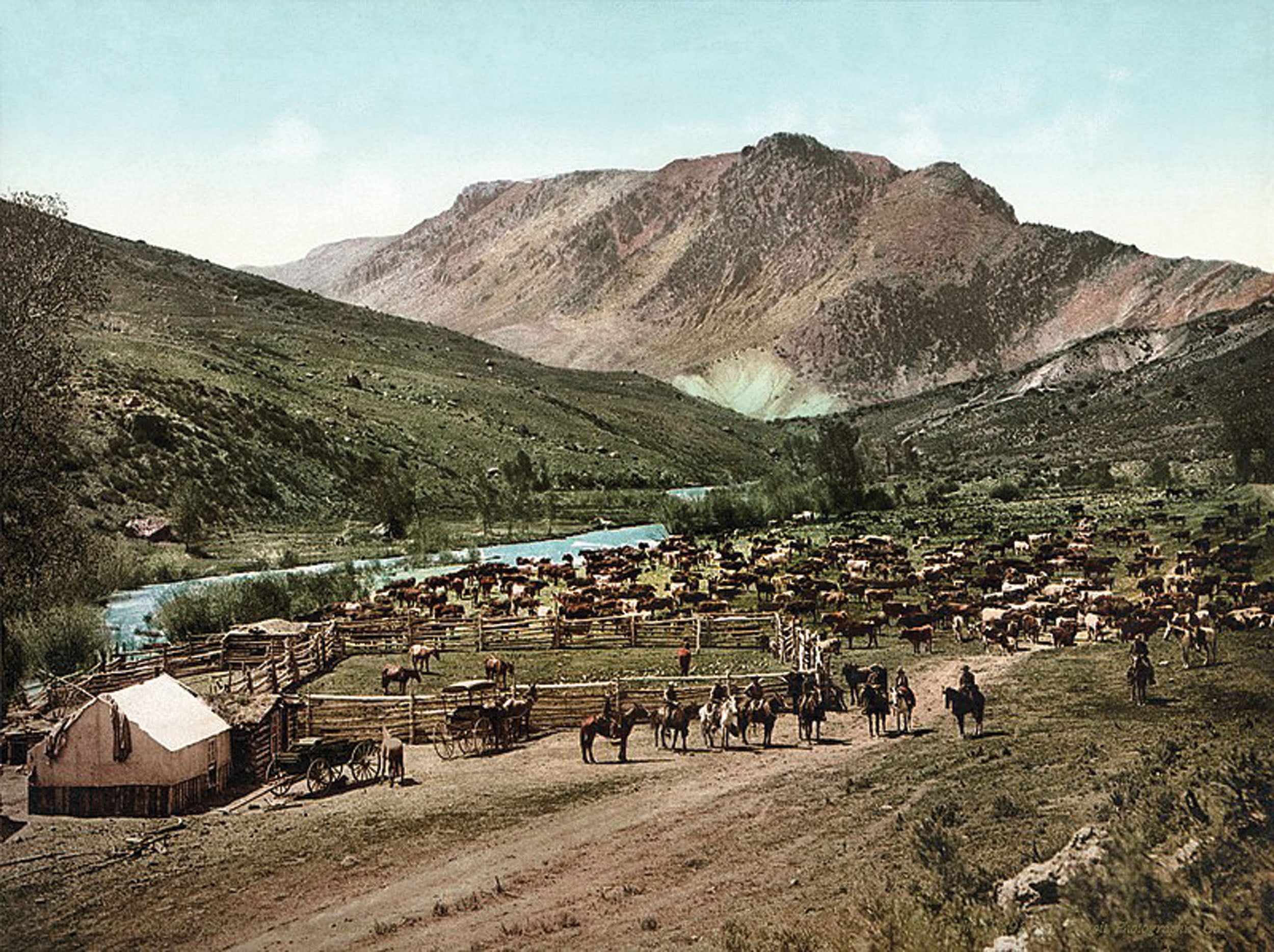

In southwest Texas, the longhorns would stray into the brasada or thick brush to eat and hide. Decoy herds of tame cattle were forced into the brush to push the wild cattle out. Corrals had been built previously where the wild longhorns were herded until tame enough to drive north. A range boss had complete authority over the horses, cattle and equipment. Roundups began very early in the spring so that the herd might head north before the grass was overgrazed.

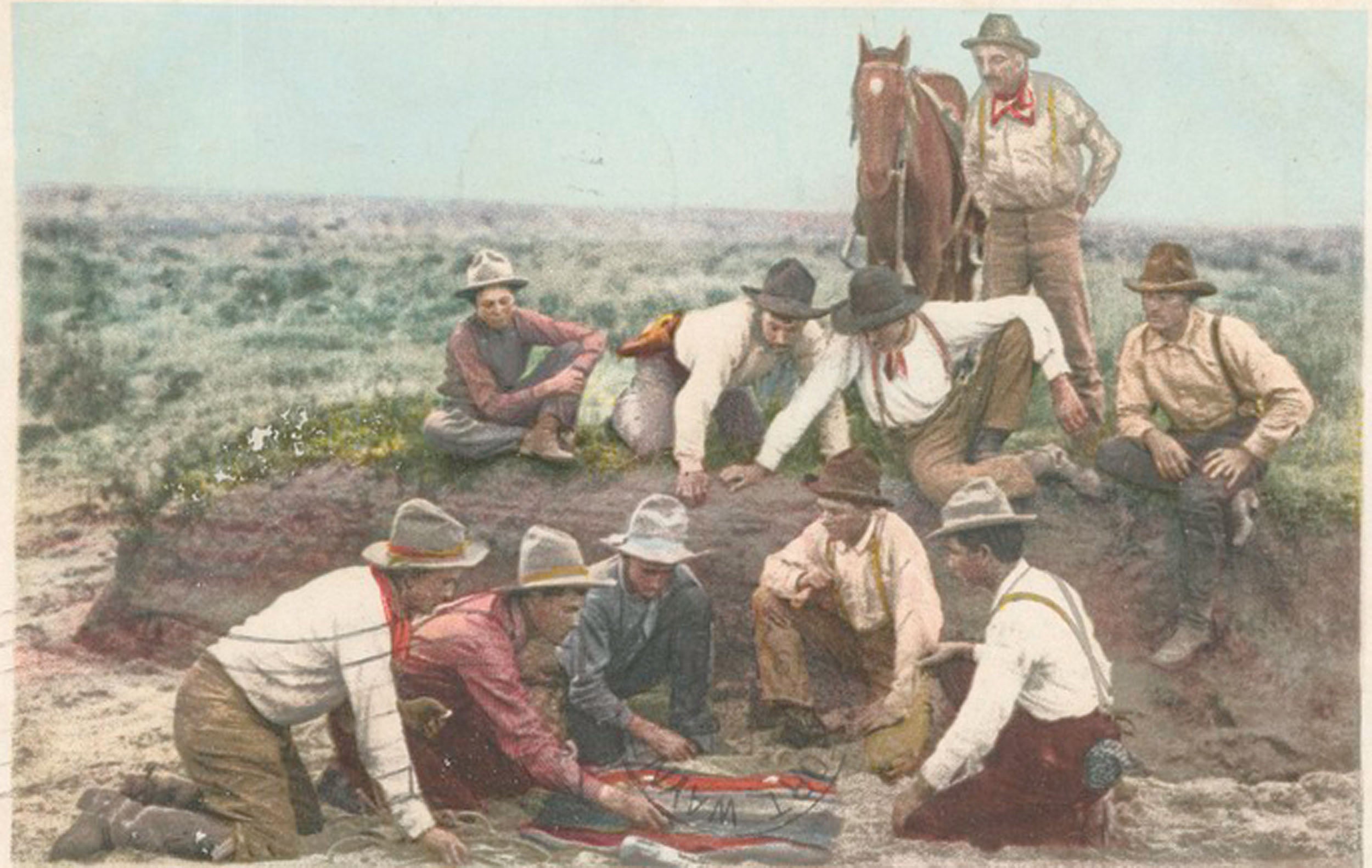

Each cowboy was to ride a certain route, bring back all of the cattle he found and place them in assigned corrals. Calves needing to be branded were separated from the more mature cattle that would be driven to cattle towns. Roping the needed cows required close cooperation between the pony (which could “turn on a dime”) and the cowboy.

Usually one cowboy could rope and drag a calf to the corral for branding. To “cut out” a steer, one cowboy had to loop the rope around the cow’s head. His buddy would try to loop the rope around the cow’s back legs. This was known as the “head and heel catches.” As soon as the unbranded cow was roped, it was herded or dragged to the nearest fire where branding irons were kept heated.

If a roundup was conducted properly, nearly every cow that had wandered off its range was returned to its own range in the summer and fall. After the fall roundup, cattle to be sold were put into “beef herds” and driven north. With Texas longhorns being classified by an owner’s brand, rustling was made a little more difficult. In Texas alone, 5,000 brands were registered on a county-state basis. By 1885 Colorado had 50,000 brands on file.

When reading an unknown brand, you read it from left to right, from top to bottom, and from outside to inside. Branding hurt the calf or mature cow. An Eastern visitor asked a cowboy if branding was painful. The cowboy replied, “Take off your pants, place your rear end on a hot cook stove for one minute.”

All sizes of herds moved north, but it was generally agreed that 2,500 was the most manageable size. For such a herd, 12 cowboys were needed (one for each 175 cows). A wrangler was a younger man who tended to the six horses each cowboy needed for the long drive. His group of horses was the remuda.

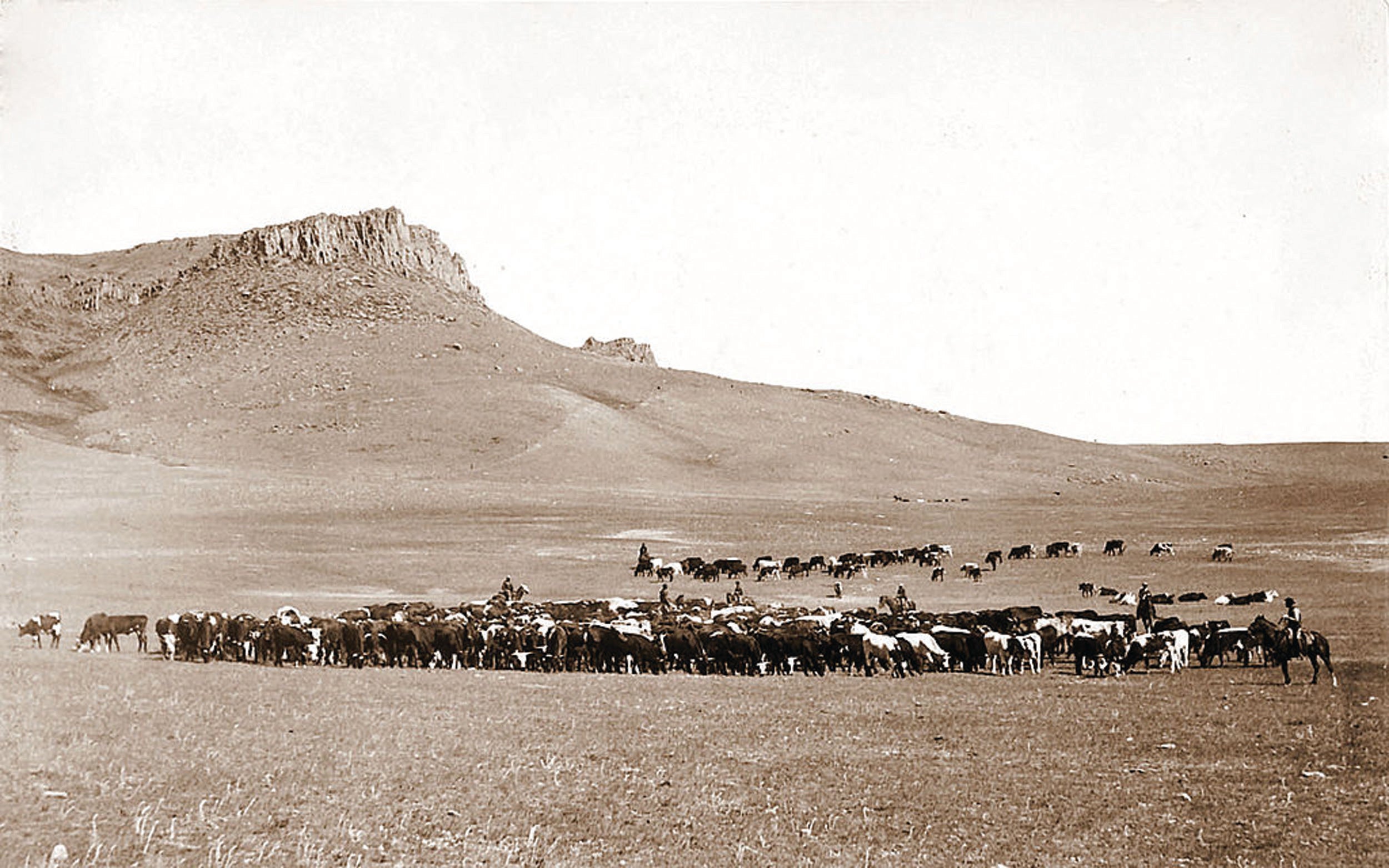

The first few days of the long drive, the cowboys tried to cover 225-30 miles a day. After that, the herd was driven 10-15 miles per day. The owner of the herd expected to have a monthly cost of $500 on the long drive. Abilene, Dodge City or Ogallala, Nebraska, could be anywhere from 1,000 to 1,500 miles from where the drive began. Dangers that could occur on the trail were stampedes, river crossings (quicksand), lack of water, Indian attacks, falling horses, rustlers and accidents to the chuck wagon.

The two most important members of the long drive were the trail boss and the cook. The trail boss was paid $125 a month and his word was “the law” for three or four months. He rode two miles ahead of the herd looking for water and abundant grass. The cowboys themselves were paid $1 per day, perhaps $100 for the entire drive, or $25-40 per month.

The cook was called “coosie” or “cookie” by the cowboys. He drove the chuckwagon ahead of the herd to the left. He had to feed the cowboys three meals a day after they have worked 15-18 hours per day. He prepared coffee, beans, meat, stew and sourdough bread and biscuits. The cowboys wanted their coffee to be “hot as hell, black as sin and strong as death.”

Cowboys consumed 2-3 quarts of coffee per day. Cooks were known to be cranky. They had to arise at 3 a.m. each day.

It was desirable to have 2,500-3,000 cattle in the herd. Ideally, the herd took the shape of an inverted “V” with the lead steer at the head of the V. In the van of the herd rode two men at “point.” One fourth of the way back were the “swing men.” Close to the rear of the V were the “flankmen.” Stationed in the rear were the “drag men” or dust eaters. Two cowboys rode night watch at two hour intervals, 8-10, 10-12, 12-2, and 2-4. They sang, hummed or whistled to ease the nerves of the herd. If a cowboy started to fall asleep in the saddle, he put tobacco juice in his eyes to stay awake.

The cow towns eagerly awaited the cowboys at the end of the long drive. The cattle, remuda, chuckwagon, saddles, bridles and loose trail gear will all be sold. The cowboy’s artificial family of 3-4 months is broken up.

Awaiting the cowboys were hotel managers, barbers, bartenders, professional gamblers, clothiers, and the “painted cats” or “soiled doves” – prostitutes. Dodge City was the original location for the “red light district” and “Boot Hill.” It became the “Cowboy capital of the world.”

Today there are 10,000-12,000 cowboys in the United States. They earn about $21,000 a year. However, cowboys do not carry tin cans of tomatoes to give their horses when they drink alkali water. There will be no more fistfights over peppermint candy in the bags of coffee.

— Bob Leith is a retired history professor from Ohio University Southern and the University of Rio grande.