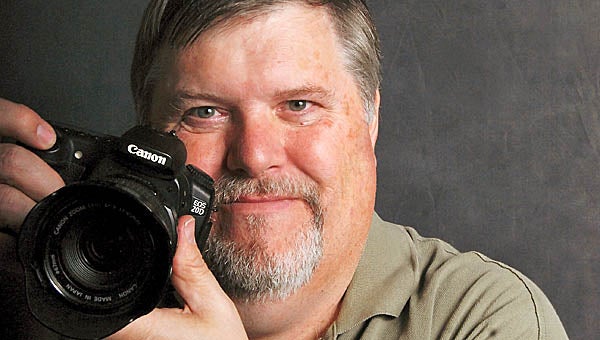

The man behind the lens

Published 11:34 am Thursday, July 28, 2011

It starts with the imagination where fantasy runs riot and everything seems possible.

It starts with the imagination where fantasy runs riot and everything seems possible.

Then when Michael Adkins has an idea firmly in his mind, he grabs his digital Canon 20D and begins transforming the pieces of that fantasy into the photograph he has envisioned.

That’s how the self-taught Huntington, W.Va., photographer has approached his work ever since he mastered the basics of the camera decades ago. It’s a journey where skill or technique or whatever you want to call it amalgamates with the mind’s eye to create art. It’s a ride Adkins finds exhilarating, at times intimidating, but always satisfying.

“Some photographers go out and look around. They can see great pictures,” Adkins said. “I create a picture in my head and then go about and find it. That is far harder to do.”

Harder? So what. Adkins does it over and over, creating a portfolio that is whimsical, complicated and overwhelmingly colorful.

“I always have a predefined conception of what the print is to look like,” he said.

It’s an approach to creating art that Adkins wants to introduce others to — both those who want to appreciate the work and those who might want to emulate. Two or three times a year Adkins passes on what he knows about the camera and how to make it a conduit to communication and creativity to classes of a dozen students at a time. His reason why is simple. That is the way his mentors long ago captured his attention and turned him into the kind of photographer he is today.

“I tell my students I am going to change the way you see the world,” he said.

“When you start getting serious about this, I want you to see something that is more than a snapshot. Something that is a work of art. Then you will start looking at things in a whole different way.”

The robust Adkins, whose quiet demeanor belies a seemingly all-seeing eye, began his journey behind the lens of a Minolta SRT 101 35. It is a camera he still has up on a shelf, primed with film and ready to go.

Adkins was stationed in Germany at an Army base in the early 1970s when his parents kept needling him to send back snapshots. Good son that he was, he obliged and got to become friends with the first photographic influence on him, Norman Lamphrey, who ran the photo lab for the service organizations over there.

“He was a tough old dude,” Adkins recalled. “He was a very good critic. I’d show him my pictures and he would verbally tear them apart and tell me to do them over. I was bound and determine to learn it the correct way.”

Next stop on the journey to becoming an artist was an unlikely venue for creative inspiration — the national chain department store, Sears & Roebuck.

“I met a lady, Barbara Solomon, who ran the portrait studio there in Huntington,” Adkins recalled.

“I wanted to learn portrait photography. She took me under her wing. I still consider her the best portrait photographer I ever met. She has been my inspiration. She is a master photographer, has an amazing eye for great portraits.”

Working with her sharpened Adkins’ technique to the point he felt ready to go out on his own, opening up his own studio, Classic Photography, in 1980 in Barboursville.

“I ran it for about three years, but studios are a tough way to make a living,” he said. “It is the second most failed business in the country. Restaurants are No. 1. It is no easier now.”

He found a day job as an information technology expert and reluctantly put the Minolta away. But out of sight isn’t always out of mind.

Five years ago Adkins found himself in the midst of a pleasant dilemma that led him back to his passion for the camera. He had just built a new house and wanted some art work for those freshly painted walls.

He found what he thought he wanted from a photographer based in Arizona. But when he contacted him, he found a commercial artist more interested in inspiring others than making a sale.

“He told me, ‘You live in a beautiful state. Why do you want to buy my stuff? Why don’t you shoot some yourself,’” Adkins recalled.

That sent Adkins out to buy his first digital camera.

“It was outside my comfort zone budget-wise, but when I got the camera back in my hands, I rediscovered my love of photography,” he said.

Now rarely does Adkins venture out without his Canon, even joking that he traded in his pickup truck for a stark white Mitsubishi Outlander that makes a much better four-wheeled camera bag.

“I used to have a truck but that doesn’t work for a photographer,” he said.

When he’s not shooting photographs or teaching photography, Adkins is talking photographs as the president of the Ohio Valley Camera Club, an organization that was founded 51 years ago and claims the famed Ansel Adams as a charter member.

“I will do anything I can to promote the club and make it dynamic and educational,” he said. “There are almost 80 members and growing. More people are in to photography. Everybody with an iPhone has a camera. We can feed on that. It is a way of sharing the passion of the members.”